Transcript

advertisement

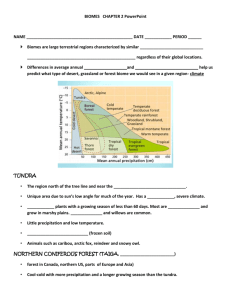

A forest dilemma: What will grow in a changing climate? Reporter: Dan Kraker Airdate: February 3rd, 2015 Our series of special reports on climate change in Minnesota continues this morning as we take you to the north woods. Imagine standing in a quiet forested glen in northern Minnesota - the sun filtering through the canopy, glinting off a nearby lake. Now, picture that scene without some of Minnesota's most iconic trees. Aspen and birch, balsam fir, black spruce - they're projected to leave the state by the end of the century, as climate change shifts their habitats northward. And many believe that if we don't lend a helping hand, Minnesota could lose much of its forest altogether. Dan Kraker reports. SFX: forrest Last fall, in a forest clearing north of Two Harbors, ecologists with the Nature Conservancy crouched over tiny oak seedlings, calling out measurements. SFX: "31-24. Six point zero." Laura Kavajecz is a graduate student at the University of Minnesota-Duluth. "We’re measuring the total height of each tree, the diameter and then the distance to the bud scale scar, so we can get at how much it’s grown this season." This careful monitoring is part of a cutting-edge experiment that just might help save the North Woods. The Nature Conservancy has planted more than 100 thousand trees on two thousand acres across northeast Minnesota. "So here we've got 500 bur oaks planted in this about one acre area or so..." Mark White, a forest ecologist with the group, says what's unusual is that in this vast forest of spruce and fir, birch and aspen -- they're planting oak, white pine and basswood seedlings. "These were the seed sources from a somewhat warmer and drier area, and so these trees may have some characteristics that make them better suited to these sites in a warmer, drier future." This is a radical shift in the forestry world, where the longstanding practice has been to plant only local trees. But models predict in the next several decades, those trees that have flourished here for centuries likely won't be able to survive in great numbers. To help understand why, I visited Lee Frelich. "I’m the Director of the University of Minnesota Center for Forest Ecology" Minnesota, he explains, is home to three distinct ecosystems, or biomes. There's the boreal. "Which is the spruce, fir, pine and birch, very cold weather type of forest. Then the more temperate, deciduous forest to the south and west. "Species like maple and oak and basswood." And then the grasslands. "So we’re really in a unique position on the continent right where those biomes converge. And all of those biome boundaries are very sensitive to climate, so we expect a lot of changes in Minnesota, more changes than a lot of other states would have." Couple that with the fact that Minnesota is warming faster than most other states. And that warming is expected to accelerate. "So we can expect the boreal forest with a business as usual climate scenario for co2 emissions for example to virtually disappear from Minnesota." Frelich and others believe boreal trees will hang on in pockets of the state. But he's already documented some deciduous species, like red maple, that are invading patches of boreal forest. There is a real fear, though, that those trees won't be able to move fast enough on their own to replace the more cold-climate adapted trees. “A lot of the research is suggesting that if we do nothing, or continue business as usual forestry, we’re not going to be able to keep up with the rate of forest loss.” Take red oak, for example. Climate models predict they'll love northern Minnesota in half a century. But Meredith Cornett with the Nature Conservancy says they can't just hop on I-35 and drive north. "You think about an acorn and it kind of drops right there, and animals might scatter it and carry it further, but not at a pace that is going to allow us to keep up with a changing climate." And forests provide a lot more than just a pretty campsite, says Wayne Brandt with Minnesota Forest Industries. "Forest products in Minnesota is the fourth or fifth largest manufacturing industry in our state, employing some 30,000 people statewide, with a value of manufactured products of about 9 billion dollars." In addition to a steady supply of everything from lumber to paper, the state's 17 million acres of forest also provide a whole host of ecological benefits. Dave Zumeta of the Minnesota Forest Resources Council says they suck up carbon dioxide, support birds and wildlife, and filter water. "50% of the water that we drink comes off of the 30% of the land that’s forested here in Minnesota. So what’s the value of that to all the city folk who drink the water coming off of the forest?" The question is - what do land managers like the DNR need to do to sustain our forests into an uncertain future? Something seemingly everyone agrees is critical, is to grow more diverse forests. A mix of young and old trees, and of different species. Think about it like a stock portfolio, Zumeta suggests. "If all you own in this last month is oil stocks, your portfolio isn’t looking too good right now." But if you have a diversity of stocks, you're likely doing a whole lot better. Same with trees. "We don’t have a crystal ball. These climate change modelers, even the best and the brightest, they don’t know exactly what’s going to happen. It's common sense that you’d want to manage complex ecosystems like forests for diversity and for resilience." That involves favoring trees projected to do better in a warmer climate. Some private landowners are already doing that with white pine, a native tree expected to be a climate change "winner." But in another experiment just underway in the Chippewa National Forest, researchers will be planting trees from much farther afield. SFX: electric saw logging Earlier this winter loggers felled red pines and sliced them into eight foot sections to haul away. In their place, says Forest Service scientist Brian Palik, scientists this spring will plant a dozen different species. "Including ponderosa pine, which grows well to the west of here in the Black Hills in South Dakota, and is suited to a drier, warmer climate. So we think it might be something that could be a potential replacement for red pine." Now, this is a highly controlled experiment. Still, the prospect of moving trees hundreds of miles beyond their native range - what's often called "assisted migration" - is really controversial. Rick Klevorn is a forestry manager for the DNR. "To bring in species that aren’t already here, that’s pretty risky I think. We don’t really know if they’ll do well here. Or maybe they’ll overly do well, maybe they’ll become invasive." Klevorn says the DNR is taking a more conservative approach. He says the agency is managing forests for more diversity, and is getting close to allowing some seedlings to be planted outside their native zones. For his part, US Forest Service scientist Brian Palik believes forest managers need to confront climate change with a greater sense of urgency. "I think I’ve had the realization that we are faced with something potentially very radical and unprecedented, in terms of the future climate scenario and habitat suitability for species we have here." Palik points to a towering red pine. He's not worried about mature trees like this one. They could live another century or more. But it's that next generation of trees - just like our future generations - that we need to make sure can endure Minnesota's new climate reality. Dan Kraker, Minnesota Public Radio News