Jones.Animalpaper

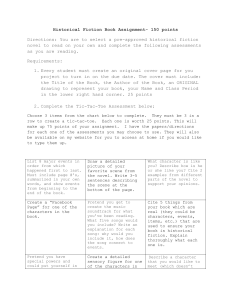

advertisement

1 Oliver Jones April 19th, 2011 CSCT 767 Dr. David Clark “The Common Destiny of Creatures”: Animal Capital and Biopolitical Sovereignty in Cormac McCarthy’s “Blood Meridian” In “Blood Meridian Or the Evening Redness in the West”, Cormac McCarthy characterizes America’s westward expansion under the aegis of Manifest Destiny as the boundless hostility of a violent cosmos towards the various life forms (human and otherwise) that populated the American borderlands in the mid 19th century. Tracking the rampages of a group of filibuster mercenaries in the wake of the Mexican-American war, the novel presents a universe where every encounter announces the possibility of violence, the potential for its outburst amplified by a logic of commodification that anticipates the ultimate convertibility of all life into capital. The coalescing of free labour and military avarice facilitates an industry as adept at transforming bat guano into gunpowder as it is at collecting human scalps for bounty. In a barren landscape thoroughly reified by the exacting gaze of military enterprise, the presence of any creature in excess of the social bond represents an affront that must be commandeered, crushed, catalogued, or converted for sale. Prefaced with a quote from the Yuma Sun announcing the discovery in Ethiopia of a 300 000 year old skull bearing evidence of scalping, McCarthy’s bleak fiction recasts the imperial expansion of the American frontier through the enterprise of free men of the Republic as an atavistic, a-historic sadism that demands ultimate conquest over every beast of the field. The novel’s particular representation (or rather “rendering”) of American expansion as the natural development of an a-historical cosmic atavism suggests the 2 naturalization of a capitalist imperialism and opens the cultural logic of McCarthy’s text to a biopolitical critique. In this paper, I will argue that “Blood Meridian” presents the historical expansion of the territorial United States as a mercenary enterprise whose hostility to life is unbounded by the process of commodification. The harvesting of living beings, human and animal, as capital is a theme which recurs throughout McCarthy’s work, and here it constitutes a crucial component in a fictionalized historical narrative that connects the mythology of the American dream with a structural metaphysics of history devoid of any teleology of historical continuity; one made in the anthropomorphic image of a de-centered, carnivalized bestiary. The novel’s staging of history as spectacle through the public execution of a performing circus bear suggests a mimetic, fetishistic “rendering” of what Nicole Shukin terms “animal capital” within a mythology of political power the constructs the subsumption of participatory nature within a tautological capitalist ecology. The novel’s representation of the rendering of animal capital suggests the essential ruthlessness of a capitalist bios that reproduces itself across the novel’s historical narrative as the genocide and wasting of indigenous populations, the mass slaughter of the buffalo, and finally the advance of the territorial infrastructure of the imperial nation state. I will argue that the spectacle of animal capital, among the dominant images within the novel’s mythology, presents an a-historic construction of a capitalist nature made in the image of war, and that this image implicates the novel’s historical mythology within a narrative of capitalist biopolitical sovereignty: “Blood Meridian” presents a boundless, perpetual war within nature as the founding gesture or instantiation of the social order and codifies this within the national mythology of the frontier. However, the mythology that grounds the novel’s organization of human community produces an unstable margin between human and non-human lives, and in the 3 ideological universe of the novel, the juridical and political question of dispensation of life and death is determined by the capricious regard of a militant capitalist necessity. Indeed, McCarthy’s inversion of Manifest Destiny posits the porous instability of the hierarchy between human and non-human animal to suggest their mutual enslavement within an eternal conflict that plays out as the expansion of the American frontier and the rise the imperial state that administers biopolitical modernity and holds sovereign power over homo sacer or bare life. As such, the novel enacts a biopolitical mythology in which the state of exception emerges in the random exchanges between a nomadic imperial capitalism and the detritus of living creatures scattered about the landscape of the Mexican-American borderlands – a state of exception which collapses biological hierarchies in the pursuit of capital and the expansion of market territory. The result is the catastrophic breakdown of biological hierarchy through the mythological production of a hostile biopolitical order where every form of life becomes a medium of exchange. As I have suggested, “Blood Meridian” mythologizes the historical development of imperial capitalism in the Southwest as the spontaneous eruption of a violent cosmology. The image of animal capital as spectacle1 is central to the development of this motif, and haunts many of the novel’s major scenes. The concluding chapter of the novel in particular mythologizes this violence as the perpetual reiteration of a cosmic dance of history, an image realized through the spectacle of a dancing bear slain by gunfire amidst the revelry at the novel’s terminal hospice in Fort Griffin, Texas. This image is significant to a critique of “Blood 1 Spectacle should be understood in the Debordian sense as the production of the appearance of society or social life through “news or propaganda, advertising or the actual consumption of entertainment” as this definition captures spectacle’s efficacy beyond the reproduction of images and suggests its singular integration as the dominant economic and social formation in contemporary capitalist society (Debord, 12-15). 4 Meridian” which seeks to interrogate the novel’s narrative investment in the “rendering” of animal capital and the history of biopolitical capitalism. The final scene describes “a dimly seething rabble...coagulated within” the interior of a bar, the assembled witnesses to an unfolding catastrophe (McCarthy, 324). Inside, An old man in a tyrolean costume was shuffling among the rough tables with his hat outheld while a little girl in a smock cranked a barrel organ and a bear in a crinoline twirled strangely upon a board stage defined by a row of tallow candles that dripped and sputtered in their pools of grease. (324) The kid, the novel’s nameless protagonist, aged thirty years and recast as “the man” by the narrator, discerns the otherworldly Judge Holden amidst the revellers, and notes intrigue involving the judge, who is seated “among every kind of man...among the dregs of the earth in beggary a thousand years” (325). The judge disappears and the costumed showman, “shaking the coins in his hat”, is accosted by the same group of men (326). An “incoherent” dispute ensues (326). One of the men draws a cavalry revolver from his hip and shoots the bear “through the mid-section” (326). The bear groans and resumes the dance in frenzy before he is shot again: “holding his chest...he began to totter and to cry like a child and he took a few last steps, dancing, and crashed to the boards” (326). The disturbing scene is central to the novel’s mythology. In the ensuing pages, the judge and the man discourse on the absence of historical telos and the murky provenance of the order of things. The judge declares the unfolding scenario “an event, a ceremony. The orchestration thereof. The overture carries certain marks of decisiveness. It includes the slaying of a large bear” (329). He explains that “the dance is the thing with which we are concerned and contains complete within itself it owns arrangement and history and finale” before adding “there is no necessity that the dancers contain these things within themselves” (329). After the judge intones 5 “only that man who...has been to the floor of the pit and seen horror in the round and learned at last that it speaks to his inmost heart...can dance” the man objects: “even a dumb animal can dance” (331). The judge is baleful: Hear me, man, he said. There is room on the stage for one beast and one alone. All others are destined for a night that is eternal and without name. One by one they will step down in the darkness before the footlamps. Bears that dance, bears that dont. (331) The novel’s final scene renders non-human life in the performance of spectacle as the archetype for a universal mythology of history made in the image of war. The novel’s fiction thereby enacts a de-historicizing representation which animates the sign of the animal within a supreme cosmology that plays out as the historical expansion of the frontier and the rise of American industry. In “The Dance of History in Cormac McCarthy’s ‘Blood Meridian’”, John Emil Sepich connects the infamous final scene with the theme of historical “cycling”, linking the novel’s mythology to a supremely bellicose order of history (Sepich, 20-21). For Sepich, the scene subsumes the novel’s key historical referents (the decline of the Anasazi in advance of the Spanish conquest of the continent, the genocidal devastation of the Navajo, the collapse of the beaver trade, “the westward reach of the pioneers...the hunt of the southern buffalo herd”) under the vindictive final judgement of a supreme or divine warfare (20-21). Sepich’s reading emphasizes the historical mythology which grounds McCarthy’s historical fiction and suggests the novel’s ruthless metaphysics of history: the novel presents the historical development of the Southwest (and the devastation wrought in its wake) as part of the sequential development of imperial powers and modes of production that brought ecological and humanitarian catastrophe to the majority of human and non-human lives subsumed within their productive matrices. Here 6 conquest is mythologized as the engine of universal history; the American frontier is but the battlefield on which imperial capitalism triumphs over every beast of the field. While Sepich’s attentive reading clarifies many of the mythological aspects of McCarthy’s narrative, he appears to overstate the novel’s investment in an anthropocentric construction of history by neglecting the connection between the scene’s sad spectacle and the delusory carnival described in the same series of sermons in which the judge declares that “war is god” (McCarthy, 249). Describing the world as “a fevered dream, a trance bepopulate with chimeras having neither analogue nor precedent” and “an itinerant carnival, a migratory tentshow”, the judge renders the history of the cosmos as a desultory menace made in the image of a carnivalized bestiary; one of unthinkable provenance and unknowable destiny (245). The description of history as a staged event (or series of events) involving chimerical illusions and the staging of animal life in an amusing spectacle has certain resonance with the judge’s conclusive ordination of war as holy force: the event ordained by the judge in the final chapter transpires in a geography bearing the name “Griffin” within a series of a carnival revels involving an anthropomorphic circus show. Indeed, the exceptional spectacle of animal slaughter in the conclusion of the novel, a tropological figure implying the divination of a restless future made in the jesting image of an eternal war at the heart nature, appears oddly attuned to the mimetic logic of rendering which Nicole Shukin critiques in “Animal Capital: Rendering life in Biopolitical Times”. Shukin describes the “rendering” of animal capital as a “biopolitical theory of mimesis” that seeks to extend the concept beyond the cultural emphasis on “realist rendition” within a critique that encompasses the economic mode of production (21). As a counter to an “overdetermination by aesthetic ideologies invested in distinguishing culture and economy”, 7 Shukin develops her biopolitical theory of mimesis as a way of implicating rendering in both the literal and figurative reproduction of the “ontological politics” and “social flesh” of capitalism (21). Developing this theory as a critique of the “ontology of production” developed by Hardt and Negri in “Multitude” (an “immanent” biopolitical ontology that curiously abstracts the reproduction of social bios from its material contingency upon “the lives of nonhuman others”), Shukin deploys the concept of rendering animal capital to extend biopolitical critique into the ideological conditions of capitalist production which “dissolve and reinscribe” species boundaries “in the genetic and aesthetic pursuit of new markets” (9-11). Shukin’s concept of rendering serves to index “both economies of representation...and resource economies trafficking in animal remains”: her theory seeks to connect the rendering practices which represent nonhuman lives with the historical modes of production which facilitate their exchange in both flesh and image (21-22). Tracking the “‘interconvertability’ of symbolic and economic forms of capital via the fetishistic currency of animal life”, “animal capital” describes “the semiotic currency of animal signs and the traffic in animal substances” and “signals a tangle of biopolitical relations within which the economic and symbolic capital of animal life can longer be sorted into binary distinctions” (7). In effect, Shukin’s critique of the rendering of animal capital describes a historical context in which the production of animal signs cannot be abstracted from the production of animal products. The fetishistic animation of animal signs within an ontology of production that renders a literal and figurative equivalence between the world of “nature” and the material relations of capitalist production appears to Shukin as the rendering of animal capital in the production of the social bios (“the form or way of living proper to an individual or group”): for Shukin, the mobilization of animal signs is concurrent with the material conditions governing 8 the destruction of non-human lives and reveals “an inescapable contiguity or bleed between bios and zoe”, one which deploys mimetic figures of animality in the fetishistic rendering of the object biopolitical sovereignty (9). Critiquing Martin O’Connor, Shukin describes the material conditions of rendering (an “industrial closed loop” resembling a tautological system integrating nature and capitalism) as one which is contingent upon a “semiotic expansion of capital...into nature” and “the discursive production of nature as participatory subject (81; Shukin’s italics). As such, the subsumption of a “capitalized nature” transpires “primarily at the ideological or social imaginary level” (81; Shukin’s italics). For both Shukin and O’Connor, the tautology of natural capitalism or “capitalized” nature facilitates the production and consumption of non-human lives through the extension of an ideology that imagines the ecological integration of capitalist production into and within nature: capitalist nature is the mystifying fiction of nature’s participation in its own wholesale exploitation. The novel’s final chapter appears particularly amenable to Shukin’s biopolitical theory of rendering, and suggests the mutual implication of material and representational processes in the production of non-human lives for consumption. The spectacle of the slain bear suggests the historical contingency of a prior mode of rendering insofar as we can understand the rendering of animal capital as the inter-formation of biopolitical power in the economic and symbolic relations that produce a commodified animality. Illuminated by the sputtering light of tallow candles, the bear is compelled to perform the mimesis of a human faculty: dance. His hapless wards exploit his labour to generate income; his movements are economized in the rendition of the organ-grinder’s mechanical time. While the scenario is more than a century removed from the context of digital rendering and “automobility” that Shukin’s theory attends, the scene 9 fictionalizes the mutual implication of the economic and symbolic in the material and figurative rendering of animal capital: recycled animal by-products maximize the visibility of the spectacle for the patrons, the bear’s temporalized movement under the spell of musical time are subsumed within the labour-time of cultural production as a use-value and exchangeable commodity. On its own, the scene would suggest the fictional representation of the mimetic rendering of animal capital in a bygone historical context, a context somewhat less alienated from the current conditions of biopolitical production (in the novel’s fiction, the immediate conditions of production and the investment of labour time are less obviously effaced than in the sanitized mass-cultural production of animal capital that Shukin attends). But the novel’s representation of a pre-industrial rendering of animal capital is significantly complicated by the scene’s situation as a coda to the historical catastrophes and ecological devastations that haunt the final chapter. Contextualized within the chapter’s broader narrative, the relevance of the scene to Shukin’s theory of rendering becomes apparent: the scene indexes the systematic slaughter of the buffalo and the proliferation of rendering industries that sprung up in its wake to a mythology that describes the encroachment of we might call a “post-historical” mode of capitalist production. The chapter, which begins with an old hunter telling a story “of the buffalo and the stands he’d made against them” (McCarthy, 316), narrates the ecological devastation of the continent as part of the sequential development of imperial and industrial modes of production. The broader narrative implicates the final scene’s spectacle in the representation of the historical violence that facilitated the expansion of the frontier. The spectacle emerges as component in a national mythology largely sustained by the rendering of animal capital. The hunter’s tale demonstrates both nostalgia and a boundless enthusiasm for the bounty of the buffalo slaughter but his narrative is tarnished by images of carnal destruction: 10 the animals by the thousands and tens of thousands and the hides pegged out over actual square miles of grounds and the teams of skinners spelling one another around the clock and the shooting and shooting weeks and months till the bore shot slick and the stock shot loose at the tang...the tandem wagons groaned away over the prairie twenty and twentytwo ox teams and the flint hides by the ton and hundred ton and the meat rotting on the ground and the air whining with flies and the buzzards and ravens and the night a horror of snarling and feeding with the wolves half crazed and wallowing in carrion (316-317). His tone shifts as he marvels at the scale of the industry. He describes driving teams heaving under the weight of pure galena lead as he re-constructs the landscape as the industrial architecture of slaughter: “on this ground alone between the Arkansas River and the Concho there was eight million carcasses for that’s how many hides reached the railhead” (317). Describing a “last hunt” two years prior, he relates how they “ransacked the country” before finally tracking and slaughtering a herd of eight animals. The gloss of nostalgia asserts itself again: “They’re gone. Ever one of them that God ever made is gone as if they’d never been at all” (317). Here, the destruction of the herds is nostalgically represented as the wasting of an historical mode of production (one which is doubled in the devastation of the hunter’s livelihood as it is in the termination of the indigenous populations’ way of life). But the man’s trek through the bone fields emphasizes a scavenging enterprise which seeks to recover use and exchange value from the waste, which can be recycled as agricultural fertilizer: “in the distance he could see a train of wagons moving off to the northeast with great tottering loads of bones and further to the north other teams of pickers at their work” (318). Indeed, the bone fields, are “filled with violent children orphaned by war”, and the remains are fodder for further antagonism among the “bonepickers”: the man shoots and kills an enterprising teenager who seeks quarrel with him over the provenance of the man’s scapular of human ears (a token which Sara Spurgeon regards as a trophy collected in the same “skewed spirit as Davy Crockett’s bearskins or Paul Bunyun’s 11 logs...as natural resources...just another part of an infinitely exploitable landscape) (McCarthy, 322; Spurgeon, 94). The narrative even notes the boy’s discarded “Sharp’s fifty calibre” rifle, bequeathed to his brother of twelve; a mass-produced object made obsolete and worthless after the exhaustion of the Indian Wars and the slaughter of buffalo (323). The chapter situates the historical continuity of the perpetual reiteration of the dance of history in the transition between the harsh, adversary production of frontier life and an over-efficient, all-consuming industrial capitalism. Sara Spurgeon describes the scene in the bone wastes as the birth of a “new covenant...in which man’s relationship to the wilderness” becomes “one of butchery on a scale scarcely imaginable” and connects the novel’s representation of “the sacred hunter” with the “governing myth of the new nation” that she recognizes in the novel’s perverse recasting of national mythology of the American frontier (Spurgeon, 97-98). She regards the wasting of the buffalo (and the industry that springs up from the waste) as the “logical culmination” of the geopolitical and biopolitical agenda the judge announces earlier in the novel: “only nature can enslave man and only when the existence of each last entity is routed out and made to stand naked before him will he be properly suzerain of the earth” (to which the judge adds “the freedom of birds is an insult to me. I’d have them all in zoos”) (98, quoting McCarthy). Spurgeon considers the logic that would have every life form “stand naked before it” as one that must destroy the world before it can reign over it as “suzerain” and she connects this logic with the “pastoral paradox” Annette Kolodny describes “at the heart of modern America’s relationship to the natural world”: “man might, indeed, win mastery over the landscape, but only at the cost of emotional and psychological separation from it” (98). She reads the novel’s narration of the encounter in the wastes as evidence of the “inexorable force of myth” driving a figure of mankind “incapable of 12 stopping, his actions governed, directed and justified by the myth his own deeds have reified” (98). In the bone fields, we see the “governing mythology” of the nation state re-emerge as the over-production of its reified edifice. Disconnected from the ecological catastrophes it wrought, the national mythology of the frontier is reproduced through the perpetual destruction of its object – the wilderness over which it claims dominion. Spurgeon’s reading implicates the novel’s narrative form within the mythic figures it animates in the retelling of history. The judge’s declaration of man as suzerain of the earth is connected with the task of writing (he is recording specimens in his notebook), a task which functions as “an attempt to bring everything under his control” by legislating that which would disappear in the absence of the observer (Snyder, 130). The question of conservation is, for the judge, entirely a question of representation, and the novel’s mythology is complicit with a representational logic that seeks to reduce or render animal life within a symbolic economy representing the entirety of nature. Indeed, the novel’s mythic reconstruction of the frontier mimics this logic: the novel’s nostalgia is tinged by the impression of the irreversible destruction of the object reproduced by its gaze. Of course, this nostalgia is no less tempered by a narrative economy that adapts mimetic representations of a historical past within a mythology describing the interminable ascent of divine war through the rampage of capitalism over the American southwest. The representational logic that would consign all birds to zoos and either draw up every creature in a ledger or expunge them from creation under the aegis of sovereign power is reproduced by a narrative which mythologizes the mimetic rendering of animal capital to aestheticize the development of a militant biopolitical order that would enslave nature within the hermetic matrices of capitalist production. This to say that the novel’s symbolic production of a nature subsumed within the arrangements of capitalist production reflects the material conditions 13 which produce the ideology (the “social imaginary”) that sustains the rendering of animal capital: the spectacle of animal capital represented in the novel’s closing scene animates a biopolitical mythology in which the bios of the imperial state is produced in the mutual antagonism between predatory wills of no fixed hierarchy. As such, the novel is both complicit and concurrent with the rendering of animal capital, albeit in a mimetic mode somewhat removed from the relations of production Shukin describes. The slaughter of the bear, an ostensibly fictional scenario which the novel deploys to suggest the sadistic triumph of industrial capitalist biopolitics over a mythological bestiary on the stage of history, suggests the historical transition between modes of rendering fetishistic images of animal life. We witness the transformation of animal signs from mythic figures grounding the production of the bios in the ontology of nature to trafficable commodities grounding the material production of a biopolitics that privileges the absolute convertibility of life as exchangevalue. Where, in an early episode, the mythic figure of a bear who attacks the filibusters acts “as an avatar of the natural world”, carrying off a Delaware scout to an unknowable fate “like some fabled storybook beast” (Spurgeon, 97, quoting McCarthy), the final scene recasts the mythic power of animal signs as a function of the material relations brought to bear within the cruel representation of the spectacle of animal capital. The judge’s final remarks suggest the tangle of the material and the symbolic in the ideological reproduction of a biopolitical mythology. His ambivalent language amplifies the connection between the staging of the spectacle and its tropological content: the language of the “floor of the pit” and “horror in the round” suggests war as a kind of theatre to be mastered by those who would aspire to the dance of history. The judge himself aspires to the dance, and we may assume that the bear’s murder spells the termination of a certain dance and its resumption 14 by a new figure of history made in the mutant image of the monstrous judge. The bear, previously standing in as an image for the mythic power of a consuming nature, is recast as a slave rendered for barter, his life and death ultimately subject to the dispensations of property law (indeed, his carcass attracts solicitors who would acquire the hide) (Spurgeon, 97; McCarthy, 333). The narrative’s deployment of this spectacle implicates the rendering of animal capital (understood as the ideological deployment of animal signs in the material and symbolic production of a participatory, “capitalized” nature) in the historical mythology which produces the history of the nation as the taming of the frontier: the slaying of the bear becomes a spectacle wherein a militant, industrious humanity is affirmed as the rightful heir and bearer of sovereign power over the bare life of an “anthropophorous” bestiary; one wholly subsumed within the economic and symbolic production of biopolitical modernity. Jacqueline Scoones describes McCarthy’s tendency to illustrate “the magnitude of sovereign power governing humanity [and explore] the ways individual life is imbedded in a system that controls the collective ‘naked life’ of all” (Scoones, 132). In a footnote, Scoones suggests that the Border Trilogy concerns an exceptional world (the Texas borderlands) where “sovereign power...has achieved absolute power over life on earth through the law of nations” and notes an interest in the “relationship between law and violence, how men construct laws in order to control human nature, and the ways in which laws justify deaths in the name of life” (152). Edwin Arnold highlights a line of dialogue in an early McCarthy screenplay that regards language as part of the technological infrastructure of biopolitical authority: “language is a way of containing the world. A thing named becomes that named thing. It is under surveillance. We were put into a garden and we turned it into a detention center.” (Arnold, 37; quoting McCarthy). 15 Both accounts suggest an abiding concern in McCarthy’s work with the biopolitical production of a representational figure (mythic or historical) resembling homo sacer or bare life. If we can discern the production of something like a figure of bare life in “Blood Meridian”, it is in the final act. The judge describes the event as “a ritual which includes the letting of blood”, suggesting something like a sacrifice. This would appear to disqualify the episode as an example of the administration of bare life were it not for the judge’s hesitations over “mock rituals” and his warning that “those honourable men who recognize the sanctity of blood will become excluded from the dance” which thereby becomes “a false dance” (329; 331). The paradoxical narration suggests the evacuation of the sanctity of life in a historical movement whereby a falsehood or deception masks or distorts the severity of the operation of sovereign power over life and death and effaces its essential violence. The murder of the bear appears as an inconsequential casualty in the novel’s construction of the historical mythology of the nation: “the great hairy mound of the bear dead in it its crinoline lay like some monster slain in the commission of unnatural acts” (327). The bare life of the animal is produced by an ignoble sacral logic which disregards the sanctity of life and death and their immanence to the production of the bios. An earlier scene aestheticizes the condition of animality common to the novel’s human and non-human figures: They struck up a fire about which they sat in silence, the eyes of the dog and of the idiot and certain other men glowing red as coals in their heads where they turned. The flames sawed in the wind and the embers paled and deepened and paled and deepened like the bloodbeat of some living thing eviscerate upon the ground before them and they watched the fire which does contain within it something of men themselves inasmuch as they are less without it and are divided from their origins...for each fire is all fires, the first fire and the last ever to be. (244) 16 Here the figure of humanity is unseated in the representation of zoe which observes a condition of living common to the illuminated gaze of those creatures sitting in mute attendance before the fire. They include domestic animals, an impoverished feral human taken under the perverse ward of the judge, the mercenaries in the judge’s company and the travellers under their escort. One might be tempted here to point towards the novel’s singular reference to “optical democracy”, a phrase Dana Phillips regards as the novel’s intimation of “the equality of being between human and non-human objects” (Phillips, 443). Surely, the image suggests an essence common to the creatures in attendance, but each one of these beings is subsumed within the biopolitical hierarchy. The bios bleeds across the zoe. Indeed, several, including the dog and “the idiot”, are slaves. McCarthy’s optical democracy does not appear to extend political recognition beyond the concern of a mercenary capitalist utility. Blood Meridian’s chief image of biopolitical power is that of blood flowing through the spatio-temporal meridian of a sovereign power made in the image of global empire. This image would appear to describe something like bare life, but the novel universalizes this image as the immanent condition of a universal ontology. The representation of all life, with humanity at the apex, as Gnostic fire in the heart of matter thrumming with the pulse of eternity entirely de-historicizes the conditions in which the subject and object of biopolitics are produced. The novel leaves us with the impression, à la Agamben’s critique of Kojève in “The Open”, of a humanity that “is not a biologically defined species” nor “a substance given once and for all”, but “a field of dialectically tensions always already cut by internal caesurae that every time separates...‘anthropophorous’ animality and the humanity which takes bodily form in it” (Agamben, 12). The bare life the novel describes appears as component of the biopolitical body produced by the novel’s historical mythology, and the mythology which animates the 17 spectacle of slaughter as the dance of history is the same mythology that grounds the discursive construction of the modern biopolitical state. The body of the slave, the “anthropophorous animal”, is incorporated within the novel’s material production of the ideology (again, “social imaginary”) that constructs and sustains “capitalized” nature through the spectacle of man’s ceremonial triumph over “beast” on the stage of history. McCarthy’s narrative presents a universe in which the wasting and destruction of life is always subject to an economy of necessity which recognizes the irreducible contingency of every object, event and encounter. As such, the novel represents an “immanent”, atavistic biopolitics of the utmost instability, where the avarice of commerce ultimately determines questions of right, typically through the exercise of violence, the outcome of which is never settled by any predetermined biological hierarchy. In doing so, McCarthy’s a-historical vision of the Southwest in the mid 19th century profoundly upsets the racialized schematic of a dignified human civilization holding dominion over every beast of the field. Instead, we see a figure of humanity perpetually constituted and reconstituted in relation to the adversary object of its antagonism; an antagonism which always threatens to unseat (or upstage) the dominant power. We are left with an anthropocentric mythology of history that reproduces an ideology that posits a demiurgic power of creation endowed in equal part in the wilderness of nature and that machinery of capitalist exploitation which would destroy it. The novel leaves us with the image of a humanity enslaved to both natural domination and the domination of nature. As such, the novel reproduces the symbolic and material relationships which construct the subject of biopolitical sovereignty and extends the exceptional ideology which reconstitutes the bios in the always-already mimetic image of the zoe. 18 In the final chapters of the novel, the kid hallucinates a visit from the judge while recovering from surgery in hospital bed in San Diego. After reading in the judges’ eyes “whole bodies of decisions not accountable to the courts of men”, the kid’s delusion transforms: “the fool was no longer there but another man...an artisan and a worker in metal” (310). Seeking “favour with the judge”, this “coldforger...hammering out...some coinage for a dawn that would not be...is at contriving from cold slag...a face that will pass, an image that will render this residual specie current in the markets where men barter” (310). The phantasm confirms the judge as both arbiter of the state of exception which administers bare life and conspiring patron in an enterprise of false transcendence which would render the ultimate equivalence and exchangeability of life as commodity. The pun on “residual specie” confirms the novel’s investment in a biopolitical mythology of capitalist history which would render all life as common stock: the kid’s dream anticipates the rise of a market society that reduces all substance to exchange value. We glimpse the birth of a world where the likeness of kind is a property of the material and symbolic relations which produce the mythology that sustains biopolitical power. 19 Bibliography Agamben, Giorgio. The Open: Man and Animal. Tras. Kevin Attell. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004. Arnold, Edwin T. ""Go to sleep": Dreams and Visions in the Border Trilogy." A Cormac McCarthy Companion: the Border Trilogy. Ed. Edwin T. Arnold and Dianne C. Luce. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001. 37-72. Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Tras. Donald Nicholson-Smith. New York: Zone Books, 1995. McCarthy, Cormac. Blood Meridian Or the Evening Redness in the West. New York: Vintage Press, 1992. Phillips, Dana. "History and the Ugly Facts of Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian." American Literature 68.2 (1996): 433-460. 12 Apr. 2011 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2928305>. Scoones, Jacqueline. "The World on Fire: Ethics and Evolution in Cormac McCarthy's Border Trilogy." A Cormac McCarthy Companion: the Border Trilogy. Ed. Edwin T. Arnold and Dianne C. Luce. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001. 131-160. Sepich, John Emil. "The Dance of History in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian." The Southern Literary Journal 24.1 (1991): 16-31. 9 Apr. 2011 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/20078027>. Shukin, Nicole. Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. Snyder, Phillip A. "Disappearance in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian." Western American Literature 44.2 (2009): 126-139. 10 Apr. 2011 <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/wal/summary/v044/44.2.snyder.html>. Sprungeon, Sara L. "Foundation of Empire: The Sacred Hunter and the Eucharist of the Wilderness in Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian." Cormac McCarthy. Ed. Harold Bloom. New York: Infobase Publishing, 2009. 85-106.