Sex Ed Works Better When It Addresses Power In Relationships

MAY 17, 2015 7:18 AM ET

MAANVI SINGH

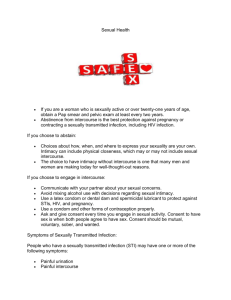

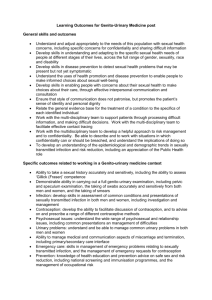

At schools that offer comprehensive sex education, students tend to get the biology

and the basics — they'll learn about sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy,

how to put a condom on a banana and the like.

But some public health researchers and educators are saying that's not enough.

They're making the case that sex ed should include discussion about relationships,

gender and power dynamics.

"The idea here is that sex is a relationship issue — you don't get HIV by just sitting

there by yourself, nor do you get chlamydia or gonorrhea, nor do you get pregnant,"

says Ralph DiClemente, a professor of public health at Emory University.

Knowing how to communicate and negotiate with sexual partners, and knowing

how to distinguish between healthy and abusive sexual relationships, are as

important as knowing how to put on a condom, DiClemente says.

So, over the past decade, researchers have developed "empowerment based" sex ed

programs that address the social and biological aspects of puberty and sex.

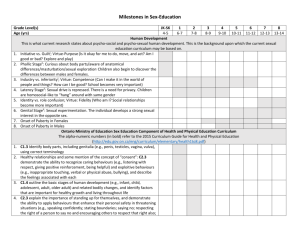

A growing number of children are entering puberty at younger ages — sometimes

as young as 6 or 7. But in many schools, sex education classes don't begin before the

fifth grade.

The programs often start out with broad discussions about gender norms and

gender inequality.

For example, SISTA — a sex ed program that DiClemente helped develop for young

African-American women — starts off by having students discuss the perks and

challenges of being young women.

And then, in addition to learning about contraceptives, they talk about how to

discuss safe sex with partners.

"They play out, for example, how do they negotiate with their sex partner,

particularly if they're in a disempowered relationship," DiClemente says. "And

maybe their boyfriend doesn't want to use a condom and is threatening to leave, to

hurt her."

The goal is to help young women feel empowered to ask for what they want from

their sexual partners. "And to feel good about themselves, so if they decide they

want to be assertive with their partner, they can do that," DiClemente says.

Michael Emberley's illustrations, like this one showing an egg traveling through a

fallopian tube, make sexual health information accessible to an elementary and

middle school audience. But elements of the art, including naked bodies, make some

parents uncomfortable.

Similar programs geared toward young men emphasize the importance of empathy

and kindness toward women and explore what it means to be a good man. And

some programs, geared toward mixed groups of men and women, include lessons

about harassment, as well as respect toward people with different sexual identities.

Elementary school students in the Los Angles Unified School District learn about

gender norms and human rights even before they learn about sex. Through a

program called iMatter, fifth- and sixth-graders learn about puberty alongside

lessons on body image and harassment. "They also learn about gender norms, and

try to break down these barriers between pink and blue," says Tim Kordic, who

helps coordinate the program at LA Unified.

The approach seems to work. A recent study published in International Perspectives

on Sexual and Reproductive Health reviewed evaluations of 22 sex education

programs for adolescents and young adults, comparing how effective they were in

reducing pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases.

It found that while 17 percent of the traditional sex education programs lowered

rates of pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease, 80 percent of the programs

that address gender and power lowered rates. All told, programs that addressed

gender or power were five times as likely to be effective as those that did not.

The results aren't all that surprising, says Nicole Haberland, the study's lead author

and a researcher at the Population Council, a nonprofit research organization

focused on sexual health.

"In the past, study after study has found that young people who adhere to harmful

gender norms have worse sexual and reproductive health outcomes," she says.

Young men are bombarded with messages that trivialize violence against women or

pressure men to be tough, Haberland says. "And in the media, women are told they

shouldn't be sexual, but they should look sexy."

By helping young people sort through these ideas and understand what healthy

relationships look like, sex education programs can help them make better decisions

about sex and relationships, she says.