FINAL-Conceptual-Performance-Framework-October

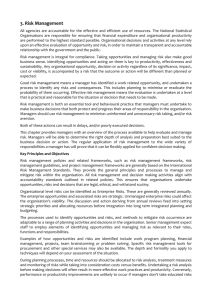

advertisement