TELA Final Draft

advertisement

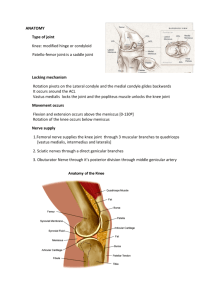

Dear Editor, The following is a Technical Explanation for a Lay Audience about the process of Anterior Cruciate Ligament reconstructive surgery. I expected this TELA to be published in your Sports Science magazine. Because of this the intended audience for the article is doctors and athletes who wish to learn more about this surgery. The overall format for this article is ‘compare and contrast’. It is meant to compare the pros and cons of each of the different types of reconstructive surgery available. I wish to publish this article in your magazine because I think it will greatly benefit the sports community, by giving those that suffer from this injury a better chance at recovery. Also a better understanding of each procedure will better equip the doctors who wish to perform this surgery. Please consider this article in the next publication of your magazine. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction What is the purpose of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL), especially to athletes participating in high-impact sports? The ACL is a very important ligament for proper knee movement and stability. A tear in the ACL is a very serious injury and reconstructive surgery is very important to athletes that wish to return to the sport. Background: The ACL is one of four major ligaments in the knee: Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL), Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL), ACL, and Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL). The ACL connects the tibia, also known as the shinbone, to the medial meniscus- that in turn is connected to the femur. The ACL prevents the tibia from rotating or sliding forward during agility, running, or jumping movements. Tearing of the ACL usually is termed “the terrible triad” because it usually consists of simultaneous tearing of the ACL, medial collateral ligament (MCL), and medial meniscus. ACL Tears are one of the most common knee injuries and are often a result of landing or planting in cutting or pivoting sports. When undergoing ACL reconstruction the selection of what ‘graft’ to use is the most important decision and contributes most to the ‘success’ of the operation. There are two types of ‘grafts’ available: Patellar Tendon Autografts and FreshFrozen Patellar Tendon Allografts. Autografts essentially use bone or tissue that has been harvested from the patient’s body; whole Allografts use bone or tissue from a ‘donors’ body, typically a cadaver’s body. The choice between the two options depends on the age and lifestyle of the patient. The study being discussed compares autograft and allograft ligament reconstruction in goats, and can be used to determine which graft is better for athletes who wish to rejoin their sport. The Experiment: The following is an experiment that was performed on goats with ACL tears to determine which of the two grafts had a higher success rate. For each graft type 20 goats underwent the surgery (20 autografts and 20 allografts), and all donors were matched for age, sex, weight, and height to the recipient. The surgical procedure is the same for each graft: exposing and removing the torn ACL then creating ‘bone-tunnels’ in both the tibia and femur for the new ligaments to be grafted into, all grafts were placed under ‘tension’ in the knee. A Lachman test is then administered- resistance to approximately 7 pounds of force and full range of motion test. Six weeks after the surgery a battery of tests were run: anteriorposterior translation, degenerative changes, and mechanical properties; this test was then run again after 6 months. The Anterior-Posterior translation test includes a range of motion test and loading test. In this experiment a load of 50N was applied to the tibia, a measurement of anterior-posterior displacement from midline was taken to graph load versus displacement curve. ‘Stiffness’ of the joint can then be calculated at a certain load by taking the tangent to the curve. Degenerative articular cartilage change test is basically an examination of the knee. The knee is divided into nine anatomic areas and given a graded score for degenerative changes. This change is compared to goats that have torn their ACL but did not undergo reconstructive surgery. The examiner is unbiased to the type of graft performed, and all goats experienced the same amount of maintenance during recovery. At both the 6-week and 6-month mark, the articular cartilage in the allograft and autograft reconstruction groups showed minimal increase in changes, compared to the control knee. Meaning that neither is favorable. Mechanical testing placed the tibia and femur at 30 of flexion and at full extension. Tensile failure tests were then conducted and measurements of the displacement of the bones were taken. The test allowed us the following information: ligament stiffness in linear loading, maximum force of the femur-ACLtibia before failure, and energy and elongation till maximum force. At 6-months after the surgery strengths of the allografts and autografts were 27% and 62% of the control ACL strength, respectively. The Results: Based on the information gathered from each test, after six months, the graft with the highest success is allografts. However, this is based on time of rehabilitation, after a longer period autografts proofed to be better. Therefore the overall conclusion is that both grafts have different strengths and weaknesses, and the selection of a graft should depend on the patient’s lifestyle. If the patient wishes to continue a career in sports an allograft is recommended. If the patient has a low impact lifestyle, either graft is acceptable.