Supporting People with Intellectual Disability to Express

advertisement

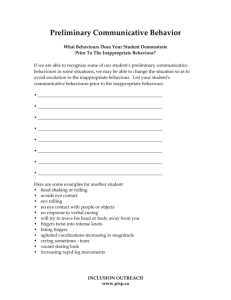

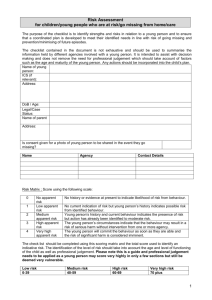

People 1st Programme A Project of Family Planning WA. Supporting People with Intellectual Disability to Express Appropriate Sexual Behaviours Elaine Alderson Manager People 1st Programme, Perth, WA. Tel. 08 9227 6414 INTRODUCTION The complex issues surrounding the sexual expression of people with an intellectual disability has gained unprecedented attention in disability policy and research in Australia over the last 10 years (1-7). This has resulted in “an exploration of alternative approaches to funding and delivering disability services with a focus on early intervention and long-term support”, a key initiative that is implemented in the National Disability Strategy (6,p.iv). The People 1st Programme (PIP), a project of Family Planning Western Australia, is committed to supporting early sexuality education for people with an intellectual disability which includes how to express appropriate sexual behaviours. In 2009, PIP was successful in obtaining two year funding from the Disability Services Commission WA to address highrisk and inappropriate sexual behaviours in people with an intellectual disability in rural WA. The findings enabled the team to deliver services in relation to sexuality, relationships, selfesteem, and protective behaviours to individuals (n=30) who were at risk of offending or had committed a sexual offence. As a result of this work, the PIP team has become increasingly aware of current issues and service gaps, which include the following: few services are available for people with an intellectual disability who exhibit inappropriate sexual behaviours. stakeholders often have difficulty in determining the point at which an inappropriate sexual behaviour warranted intervention. the display of this type of behaviour places the safety of the person and others at risk. there is risk of exclusion from facilities and services vital to the person’s health, development and wellbeing. the lack of effective education leads to a scenario in which people with sexual behavioural issues do not get help until after the police are involved. Care staff typically have little confidence in their ability to support people and tends to have received little training in the topic area, giving rise to the formation of negative attitudes. Terminology A note on the term ‘inappropriate sexual behaviours’ is essential. Inappropriate sexual behaviours are not necessarily associated with people with an intellectual disability. However they have been reported to be more common in the population than in the nondisabled population (7-11). It is estimated that “challenging behaviours including inappropriate sexual behaviours] are 3-5 times more common in people with an intellectually disabled than in the general population” (7,p.198). In particular it has been identified as a common presentation in men with intellectual disabilities (12-14). It is with the above in mind that we consider the following: What is expected childhood sexual development? What is age appropriate/inappropriate sexual behaviour? How do we recognise better recognise inappropriate sexual behaviour and at what point is intervention required? Given the overrepresentation of people with intellectual disabilities in the justice system (21:50-52), what is the impact of a criminal conviction on these people and their family members? Solutions The project identified the following solutions: Solution One: Develop a sexuality assessment tool to determine knowledge pre and post one to one education. Education material assessed a range of topics to assist individuals to: develop skills required to distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate sexual behaviours; make responsible sexual decisions (e.g. establishing sexual boundaries); promote self-esteem, assertiveness skills to assist the above. Solution Two: Develop a training tool for families, carers and disability workers to recognise inappropriate sexual behaviours , The tool will assist: families, carers and disability workers to recognise inappropriate sexual behaviours at an early stage; implement strategies to manage behaviours; families, carers and disability workers to make referral for education and counselling before offences occur; and criminal justice staff to work effectively with people with an intellectual disability to prevent re- entry to the criminal justice system. In short, the People 1st Programme (PIP) supports healthy sexual expression in people with an intellectual disability through education and training. Equally, the PIP advocates the implementation of a National Disability Insurance Scheme, pushing for greater choice and control over sexual decision-making and safe respectful relationships for people with disability. An Overview of the Literature This literature search and summary focuses on the sexual behaviour in children and young people, 0-18 years, with specific attention to age and development related sexual knowledge and behaviour among people with an intellectual disability. More broadly the review looks at differentiating expected sexual behaviours from inappropriate sexual behaviours, identifying underlying influences on sexual behaviour and the factors that may affect frequency and type of sexual behaviour, and, identify current, effective intervention programs. Source material includes current journal articles, papers, excerpts of relevant texts, government policy guidelines and web based literature. The scope of content includes data from relevant law; education; allied health; medical; disability service; and community organisations originating from current Australian, Canadian, British, New Zealand and USA research. This literature search was undertaken in order to better inform the development of the tools that and will enable the People 1st Program (PIP) to better support families, carers, teachers and disability workers to recognise inappropriate sexual behaviour in people with an intellectual disability, and, to recognise the point at which the behaviour requires intervention. The focus of the literature search attempted to address the questions posed. The findings of the literature search will help to guide the development of an effective, early intervention training program and associated resources and inform further investigation into areas that lack clear evidence based literature by identifying the gaps in existing research. Summary: Sexual Behaviours in Children and Young people Sexuality is an innate part of all people they “are sexual from birth to the grave”. Sexual behaviour develops on three levels, biological, social and psychological (54). A child’s sexual development is expressed in a range of behaviours most of which are healthy and expected (17;20;24;32;35). When sexual behaviour becomes other than this it is considered inappropriate sexual behaviour. All behaviour has a function and communicates a need, desire or want, thus highlighting the need for adults to look carefully at behaviour to determine their need. When sexual behaviour is determined to be inappropriate, determine why; boredom, anxiety, gender issues, lack of boundaries, curiosity, need for physical activity to name a few (25;32). Understanding the need may assist in early identification and determination of the behaviour of concern. There is no single set of definitive guidelines that determine appropriateness or inappropriateness of sexual behaviour among individuals. However, there is an acceptance of a set of general guidelines that prescribe age and development groupings, by which sexual behaviours are determined to be appropriate or inappropriate. There is consistency throughout the literature on the range of sexual behaviours considered appropriate and those considered inappropriate. The literature clearly supports the idea that expected, appropriate sexual behaviour is healthy and driven by a curiosity that is explorative, light hearted and between equals in age, size and ability (16-18;23-25;27-29). Children’s expected sexual behaviour is limited in type and frequency and is balanced by interest and curiosity in others aspects of their lives. Behaviours are often exhibited in games between willing participants of equal age and ability. Expected sexual behaviour is also characterised by responding to adult intervention, the ability to redirect the behaviour when guided. As children grow and develop the range and type of sexual behaviour changes reflecting age appropriate physical social and intellectual development, family and social norms and peer culture. Inappropriate sexual behaviours, those that cause concern or require professional help, are generally characterised by range of activities that can be persistent, frequent, harmful and/or between unwilling or unequal participants in age/size/ability, negatively impact on others and are outside of federal and state legislation (16-18;20;23-2527-29;) and escalate from ‘expected’ to concerning sexual behaviour even after redirection and intervention (16-20;2229;31-33;35). The continuum of behaviour from ‘expected’ to those a ‘cause for concern’ and need to seek professional help’ characterised by intent, persistence and preoccupation of inappropriate sexual behaviour. Inappropriate sexual behaviours includes a broad ranges of activities from peeking, touching, rubbing, inappropriate questioning, crude talk to masturbation, oral sex, sexual intercourse and penetration of dolls, children or animals (22;24-25;32;39). The intention of the new ISB tool will include, at one end of the continuum the expected behaviours. At the other end of the continuum those that need to seek professional help. The new tool will look to adapt and replace what we consider ‘value laden’ behaviours i.e. promiscuity and aim to include the promotion of respectful relationships in its design. Sexual activity between children and young people who differ in age, cognitive ability or physical stature and size is considered inappropriate (20;24;33-36;35-38). Quantifying inequality of age varies in the literature however according to the Australian Institute of Family Studies; an age difference of more than three years is considered unequal (21). Inequality between participants presumes a lack of informed consent, dominance of one over another, pressure and coercion, and, advantage. Sexual behaviours that fall outside of the legal framework often result in participants having contact with the justice system and clinical support agencies. The legality of ISB is a determinate set by federal and state criminal codes, duty of care statements by relevant government organisations and departments and influenced by international natural justice rights, the management policies of care facilities (31;25;33;36). The tool will include specific behaviours observed in the client group by sexuality educators and counsellors in WA. Many consider the rubbing of genitals as sexual which may actually be sensory, boredom or emotional behaviours’. The teaching session will look to distinguish between them. The literature shows differences in the age group ranges used to determine appropriate and inappropriate sexual behaviour, in part, reflecting the discipline of the author, the target audience and the country of origin. The groupings are based on generally accepted developmental levels for a particular age group, infancy, childhood, pre-adolescence and adolescence, with some literature refining the span of age groups to reflect their specific educational need (20;24;53) . The age group spanning six years, 13-18, is consistently used as a determinate of adolescent sexual behaviour with only one reference to a more refined range to reflect the subtle developmental changes within this group(25). The tool will look to redefine the age groups in line with sexual development, the age ranges will be evaluated when delivering the tool during teaching. The literature regarding sexual behaviour among children and young people with intellectual disabilities highlights a number of challenges that makes these people more susceptible to developing behavioural problems (16;20;38). Individuals may encounter difficulties in understanding social norms, boundaries, personal space and the concept of ‘public’ and ‘private’. They may encounter challenges with communication, being unable to communicate their needs or understand the needs of others, often not understanding what is hurtful or comfortable to others. Poor impulse control and distractibility is common. In evaluating sexual behaviours in people with intellectual disabilities often development levels and cognitive ability is the focus rather than chronological age as the child may exhibit behaviours that are consistent with their development level but be considered inappropriate for their age. However when it comes to legislation chronological age is always taken into account hence the need for early intervention despite cognitive ability. It is important to note that any particular sexual behaviour, abuse or not, cannot always be determined based on the behaviour alone, contextual assessment should be included. Inappropriate sexual behaviour may include physical, verbal or psychological coercion resulting in, for example, a less able child exhibiting inappropriate sexual behaviours. The context of the behaviour can be complex. The type of sexual behaviour discussed is consistent in all of the literature reviewed, while specific behaviours cited (within type) are varied. Behaviours that are considered outside the norm, ISBs, are generally consistent within the review literature and similarly consistent in there placement into the categories designated cause for concerning and seek help. However, given the relatively broad scope of these categories plus differences in settings, culture and experience there is much room for placing specific behaviours into the categories. As a result of the above the project will draft a response tool to further assist family members and disability support workers. Influences on Sexual Behaviour The development of ISBs in children has been attributed to the following experiential categories that impact on exhibited sexual behaviour (17;20). 1. Expected Sexual behaviour: as described previously 2. Reactive Sexual Behaviour: children exhibit sexual behaviour because of what they have seen and /or experienced as a means of coping with emotions such as loneliness, fear and anxiety. These behaviours are learned and reinforced by others (often from within the family). Reactive behaviour is spontaneous, unplanned and impulsive. 3. Sexualised Behaviour: often includes secretiveness and for some children becomes the norm. These children often try to engage in sexual behaviour and learn that sexual arousal can compensate for unpleasant feelings. 4. Coercive Sexual Behaviour: children who abuse others and have a range of behaviour problems. These children are not like others and will stand out by being sexually or physically aggressive, have few friends, and may befriend less competent, younger, smaller children, or use force to achieve goals of dominance. Children in this group plan their actions. Learned responses together with, and most likely integral to, the development of inappropriate sexual behaviour include biological influences (puberty); family values and attitudes; social norms; peer group norms; living conditions; amount of exposure to adult sexuality, nudity, explicit media, and individual developmental level (16;17;18;21;26-29). At puberty, commonly 9-16 years for girls and 13-15 years for boys, there is a change in body shape and physical size driven by the dramatic changes in hormone levels. There is evidence that the age of onset has decreased over recent decades with boys in many developed countries beginning puberty between 9.5 and 12 year and girls around 13 years (18;42;43). Early onset of puberty has been associated with illness (particularly in girls), obesity and poorer socio-economic and living conditions (18;39;42-43) Research has linked both stage of pubertal changes and the timing of puberty to adolescent sexual behaviour (18;39;42;43). It was found that in both genders earlier onset of puberty relative to peers was associated with greater sexual experience (39-40;42-43). Among girls, early menarche, first period, was associated with younger age of first intercourse and among boys advanced pubertal maturation relative to peers was associated with earlier first intercourse (40-43). Not surprisingly the influence of family, society and peer groups attitudes, values and norms have been cited in the literature as being influential to a child’s sexual behaviour. Child parent relationships, parental control and child-parent communication have all been implicated in adolescent sexual behaviour. Better parent-child relationships are linked with delayed sexual intercourse, less frequent intercourse and less sexual partners (16;18;40;43). Norms within the society in which one lives are learned or experienced at an early age and help form the basis for all behaviour. How adults treat and care for one another will influence how children will interact with members of their own and the other sex (18;20;34;42-43). Sexual “Negative and stereotypical attitudes (often toward women) are commonplace among boys and men, not specific to sexual offenders.......it emphasises that such behaviour is tacitly and sometimes explicitly condoned within the cultural context of many (young) people. (21,pp1) Situational factors such as sexually explicit language, access to explicit television and other media and unsupervised internet access have been mentioned in the literature as an increasing influence on child and adolescent sexual behaviour and ideation (18;19;23;34) There is also consistent association found between family socio-economic status and adolescent sexuality. The lower the family income and parental education level the greater the likelihood of teenage intercourse (18-20;42-43). Peer influences have long been assumed to exert a strong influence on child and adolescent behaviour within their group. Peers being a major source of information about sex, providing a ‘norm’ for sexual activity, a benchmark for acceptability and an opportunity for sexual experimentation (18;20;39;42). Intervention for Inappropriate Sexual Behaviour On drafting the Response Tool the team reviewed current literature from various countries. Within the literature reviewed it is universally agreed that intervention at the lowest level, expected behaviour should only require a description of the behaviour with the participant(s), a statement of impact on others and prohibition of the behaviour. Dependent on the setting the incident may need to be recorded as a benchmark for potential future behaviour. Continued ISB will demand further intervention (17;16;23;32). The project team considered that redirection of the behaviour be included in line with positive behavioural practices. Intervention required for ISBs is characterised by sexual behavioural exhibited, setting of the incident, impact it has on others, if it is outside the law and relevant guidelines and policy. Sexual behaviours that trigger the need for intervention vary widely and are too numerous to mention but the commonality is that the behaviour is considered inappropriate for the child’s age, the setting in which it occurs, involvement of others, the intention of the behaviour (predatory, coercive) and the persistence with the behaviour (23;25;26;32;34;36). The person(s) who intervene will vary depending on where the behaviour is exhibited, the severity of the behaviour and whether others are involved. Those who typically are the initial intervener include parents/guardians, teachers/principals, and carers. If the ISB escalates and becomes persistent, disruptive to self or others, harmful to self or others and/or illegal (20;23;34), the intervention broadens to include therapists, mental health professionals, counsellors and if appropriate the police. Intervention strategies are framed as a continuum (20;23;32) from verbal redirection to multidisciplinary approaches in serious cases. The continuum is based on the three categories of ISB, Expected, and Cause for Concern, Seek Professional Help. Expected sexual behaviour predominantly does not require intervention but does provide an opportunity to give positive feedback, age appropriate information and if necessary set boundaries. If ISBs are considered to be a cause for concern intervention includes observation, gathering information to determine and the implementation of an appropriate response, that is, education and/or counselling. Inappropriate sexual behaviour considered necessary to seek professional help requires immediate response that includes contacting and working with parents/guardians, care facility staff and any appropriate services. The type of intervention is dependent on the type of ISB, the category in which it is placed and the impact the behaviour has on others. Literature that includes data on response to ISBs commonly includes discussion with the participants describing their behaviour and ensuring avoidance of a repeat of the behaviour with a statement of impact on others and the intervener. Reporting the incident to a line manager, principal and recording the incident in order to establish a potential benchmark for future behaviour. It is recommended that parents of children be informed of the incident with a cautionary note to reassure the behaviour is considered within the expected range and is a first incident. Escalating to include specific education or training, restricting the participant(s) contact with others or from the facility altogether, involvement of allied health professionals to assist in assessment and treatment and involvement of the police, social services and child protective services (16;20-21;36;44). The literature regarding specific needs and intervention for children and young people with intellectual disability is very scarce and it seems that little effective intervention is provided and as such carers and teachers had difficulty recognising the initial point of intervention. (23;38;45;46). This indecision is then compounded by the fact that the exhibited ISB “place(s) the safety of the person and others at risk, or there is a risk of exclusion from the facilities and services vital to the person’s health, development and wellbeing” (47,p.22). In many cases, lack of effective intervention leads to a scenario in which “people engaging in inappropriate sexual behaviour do not get help until the police have become involved” (37,p2), (48-49). The Response Tool will take into consideration the above factors and include specific strategies during the teaching session. People with disability may also be at risk of victimisation. Young people with an intellectual disability may be at greater risk of abuse and neglect due to a number of reasons i.e. poor boundaries being too trusting and inability to make informed decisions. (23). The literature suggests that people with an intellectual disability may be overrepresented in the criminal justice system (21;50) and the question of over representation is linked to the expressed concern that “people with an Intellectual disability may be disadvantaged by the criminal justice process” partly due to their ‘mental impairment’ (50-52).Within WA we are aware that additional charges are often obtained due to poor behavioural control and understanding at the time of arrest. This further impact on the individual and family members. The development and provision of accessible facility management policy and procedural documents provides staff with specific information on reporting, documenting, monitoring and escalating incidents of inappropriate sexual behaviour (17;20;26;34). Guidelines for intervention, reporting and monitoring incidents ISB go some way to reducing the feeling of indecision care staff may experience when confronted with an incident of inappropriate sexual behaviour. Parent / Disability Support Worker Training and Education The project aims to deliver two teaching sessions with the aim of increasing knowledge, skills and confidence to define and manage specific behaviours. The literature reports widespread evidence of fatigue and additional mental health issues among parents and carers due to the demands of caring for a child or young person with an intellectual disability (23) Lack of confidence among care staff to support children and adults engaging in ISB is well documented in the literature and many tend to have received little training in supporting individuals, as a result “negative attitudes toward the persons behaviour ensues”, (14;5). There is clearly a need to provide effective, timely, ongoing training for people responsible for the health and wellbeing of people with an intellectually disability. Provision of training to help parents, carers and disability workers better identify inappropriate sexual behaviour at its earliest stage may reduce the escalation, severity and repeated occurrence of behaviours that adversely impact lifestyle and opportunities There is a lack of research available on effective training for carers, teachers, support staff and parents of children and adults with intellectual disabilities that potentially could enable early recognition of ISB, identify early intervention and provide response/risk management strategies. Some generic tools are available however age groups appear vast and some specific behaviours observed in the client group appear absent. The teaching session will assist to close the identified gaps. Sexuality Education for People with an Intellectual Disability While much has been written about sexuality education in mainstream populations less is available that focuses on sexuality education for those with intellectual disabilities. While it is commonly agreed that appropriate, relevant developmentally timely sexuality education be part of a holistic approach to health and wellbeing, applying this to people with intellectual disabilities can be challenging for both parents and educators. The literature shows that parental concern about the potential of abuse among their children is a realistic possibility (17;21;53) increasing parent’s need for assurance of a quality sexuality education program for their family members. Since 1994 the PIP service has included protective behaviours in its sexuality education programmes and promotes its inclusion in sexuality education in schools and adult placements. The Impact of a Criminal Conviction Available literature on the impact of a criminal conviction on people with intellectual disability(s) is very limited. What little information there is can be summarised as follows. Among young people, 13-18 years, young men and boys are the vast majority of offenders, however, younger children can harm or distress others by their sexual behaviour and children aged 10 or over can be held criminally responsible in most states (21;53). There is also some recent research from the USA identifying adolescent girls as sexual perpetrators, however, the rates of abuse are small, less than 3%. Generally the research indicates that young people who offend against children are more likely to be socially isolated and have poor social skills while those who offend against peers or adults are more physically aggressive. The cycle of victim-to-offender idea, the abused becomes the abuser was a popular notion and it has been used to explain sexual abuse for some decades. Recently there has been dispute about this theory. Primarily the research underpinning the theory is thought to be inconclusive and importantly the role of gender and power is minimised. While there is little written about the impact of a criminal conviction on young people generally there is even less that specifically focuses on the person with an intellectual disability who offends. From what has been published some inferences can be made. Removal of the offender from the home and involvement of protection authorities and police may cause distress, fear, anxiety, confusion, guilt and perhaps a lack of understanding of the implication of the abuse. It is well known that once an individual has been charged several charges are known to be served as a result of the impact and inability to manage the situation as it occurs. The reality of supervision, monitoring and/or imprisonment may cause feelings of isolation, fear, guilt and intimidation. The reaction of the family of the offender can include anger, shock, disbelief and confusion, more so when the abuser and victim are from the same immediate family. Negative feelings toward the offender may continue and impact on future relationships. Impact on potential employment may be adversely affected as the conviction will be recorded against the offender. Work choices become further limited following offences against children. It is clear from the lack of published work on the impact of criminal convictions on people with intellectual disabilities that there is a need for sound, current, evidence based research to inform development of intervention. The project will develop this concept further to include the impact on the person’s lifestyle and their family members. Conclusion It has been made clear that children and young people develop physically, mentally, emotionally and sexually through exploration, observation and processing the information gathered. Like all human development, sexual development begins at birth and includes not only the physical changes in children but also changes in sexual knowledge and behaviours. Inappropriate sexual behaviours are generally determined against what is accepted as age and developmental norms which are categorised into Expected Behaviours, those being a Cause for Concern and those serious enough to Seek Professional Help. While some difference occurs in the age range generally the type of activity exhibited is consistent. Identifying ISBs at an early stage is often difficult for parents, carers, teacher and others working with children and young people. The determining factors that are commonly used as markers for ISBs include frequency, persistence, preoccupation and intent of the exhibited behaviour. ISBs at the earliest stage warrant redirection and depending on the behaviour, age and impact to self or others can escalate to a situation whereby professional intervention is required. Often a multi-disciplinary approach is recommended as a best practice model. Sexual behaviour is like all behaviour and has a function and purpose and like all behaviour at times the influences are complex and interrelated. There many influences on sexual behaviour include onset of puberty, early puberty, age of first menarche; family, societal and peer group norms; socio-economic status and exposure to explicit media at early age. Sexual behaviour should be assessed contextually and not in isolation of other factors and influences. Interventions to address ISB include determining the antecedents, redirection of the behaviour, additional support; education and treatment. The need for early identification and intervention is important to future education and training programs. Disability support staff report a lack of confidence in their capability and confidence to intervene and report negative feelings toward the ISB. The lack of carer and staff training and education is widespread Children and young people with an intellectual disability can be susceptible to developing inappropriate behaviour due to difficulties with communication, understanding public and private concepts, impulsivity and lack of appropriate sexuality education. Young people with intellectual disabilities are also vulnerable to abuse and neglect and are at risk of victimisation. Generically sexuality education is not provided at an appropriate level to equip children with the information and skills needed to understand their sexual development and behaviour. Evidence suggests that people with intellectual disabilities are over-represented in the criminal justice system. Intellectual development, poor impulse control, lack of understanding of behaviour and consequence, environment context, poor communication skills are only some of the factors that contribute to the representation of intellectually disabled people in our criminal system. As the published data on the impact of a criminal conviction on a young person with intellectual disability is scant the PIP team conducted a small sample survey to gather some informal data. The survey was undertaken by participants of two related workshops where the participants represent the families, teachers and support staff of the target group (see Appendix Four). The consequence of a conviction can be far reaching and affect the perpetrator and their family, support persons and their wider social networks. For the purpose of the survey the consequences were divided into three categories, at the time of conviction; during the sentence and post-conviction. Similarly, the effect of the conviction was divided into the physical, emotional and mental impact of the perpetrator and the family, friends and others working with or supporting the individual. The emotional impact of engaging in sexually inappropriate behaviours and/or being charged can include shame, guilt, fear, rejection, blame, stress, loss of trust and confusion. The physical impact can include bullying, isolation, STIs, pregnancy, a loss of job/home/money/freedom, risk of harm and injury. The involvement of the Sexual Offenders Monitoring Services are seen to be time consuming, invasive and reduces options for other activities to ensue. It is commonly believed that a criminal conviction for people with intellectual disability negatively impacts every aspect of their lives. Recommendations Further investigation into: 1. Effective sexuality education is required. The evidence focusing on education for people with intellectual disabilities presently is scant. While age appropriate sexuality education is widely accepted as part of a holistic approach to education in the general population there appears to be a reluctance, ignorance and lack of ‘expertise to deliver appropriate programs. A reluctance and ignorance of the need to recognise that people with intellectual disabilities need and are entitled to sexuality education, a reluctance to undertake the task and a reluctance to ‘expose’ children to information that may be considered inappropriate. There is widespread feeling of lack of confidence to recognise inappropriate behaviour at an early stage, a lack of confidence to deal with it once recognised and a lack of confidence to undertake sexual health education. 2. The impact on young people with intellectual disabilities who are convicted of a criminal sexual offence is required. The data on numbers of sexual offences committed by young people generally is considered unreliable and data gathered that involves young people with intellectual disability is even more incomplete. Under reporting is a contributing factor as victims are often reluctant to come forward as they may feel ashamed, anxious or fearful of reprisal from the offender. Added to this is the lack of a standard definition of intellectual disability within the legal framework (55), those working with intellectually disabled offenders have difficulties with identification, proper assessment and effective treatment for offenders unless incarcerated or ordered to attend diversionary programmes . These difficulties have made accurately reporting rates of offenders with intellectual disabilities all the more challenging. Accurate data is essential to guide future development of programs that focus on identifying offender characteristics, identifying effective intervention and educational/treatment programs. References 1. Disability Services Commission. Who Can Help: Sexuality 2012 (cited 22 June 2012. http://www.disability.wa.gov.au/health/sexuality/sexuality_help.html?s=304143818.) 2. Scheermeyer, E. van Driel, ML. (2012) Intellectual disability, sexuality and sexual abuse prevention - a study of family members and support workers. 3. Commonwealth of Australia. 2011. 2010–2020 National Disability Strategy. 4. Kelly, Glenn, and Grahame Simpson. 2011. Remediating Serious Inappropriate Sexual Behavior in a Male with Severe Acquired Brain Injury. Sexuality and Disability 29:313-327. 5. Noonan, A, and M. Taylor Gomez. 2011. Who’s Missing? Awareness of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People with Intellectual Disability. Sexuality and Disability 29:175-180. 6. Productivity Commission. 2011. Disability Care and Support, Report no. 54, Canberra. 7. Woods, Robyn. 2011. Behavioural Concerns: Assessment and Management of People with Intellectual Disability. Australian Family Physician 40 (4):198-200 8. Eastgate, Gillian, Elly Scheermeyer, Mieke L van Driel, and Nick Lennox. 2012. Intellectual Disability, Sexuality and Sexual Abuse Prevention: A Study of Family Members and Support Workers. Australian Family Physician 41 (3):135-139. 9. Tsatali, Marianna S., Magda N. Tsolaki, Tessa P. Christodoulou, and Vasieilos T. Papaliagkas. 2011. The Complex Nature of Inappropriate Sexual Behaviors in Patients with Dementia: Can We Put it into a Frame? Sexuality and Disability 29:143156. 10. Embregts, P, K van den Bogaard, L Hendriks, M Heestermans, M Schuitemaker, and H van Wouwee. 2010. Sexual risk assessment for people with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities 31:760-767. 11. MacKinlay, L, and P. E. Langdon. 2009. Staff attributions towards men with intellectual disability who have a history of sexual offending and challenging behaviour. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 53 (9):807-815. 12. Lindsay, William R. 2009. The Treatment of Sex Offenders with Developmental Disabilities. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 13. Sajith,S.G.,Morgan, and D. Clarke. 2008. Pharmacological management of inappropriate sexual behaviours: a review of its evidence, rationale and scope in relation to men with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 52 (12):1078-1090. 14. Willner, P, and M Smith. 2008. Can attribution theory explain carers’ propensity to help men with intellectual disabilities who display inappropriate sexual behaviour? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 52:79-88. 15. Kelly, Glenn, and Ann Parry. 2008. Managing Challenging Behaviour of People With Acquired Brain Injury in Community Settings: The First 7 Years of a Specialist Clinical Service. Brain Impairment 9 (3):293-304. 16. Kellogg ND (2009), Clinical Report: the evaluation of sexual behaviour in children. Paediatrics, 124, 992-998. 17. Johnson, T. C. (1998). Understanding children’s sexual behaviours: What is natural and healthy. 18. Crockett LJ, Raffaeli M, Moilanen KL (2003). Adolescent Sexuality: Behaviour and Meaning. Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology, Paper 245 19. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network: Sexual Development and Behaviour in Young Children, Parent and Carer Information, 2009. 20. British Columbia, Ministry of Education (1999). Responding to Children’s Problem Sexual Behaviour in Elementary Schools: chapter 1: Childhood Sexuality. 21. Boyd C, Bromfield L (2006), Young People who Sexually abuse: Key Issues. Practice Brief 1 2006, Australian Institute of Family Studies. 22. www.nspcc.org The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children: Sexual behaviour of children: what is normal, worrying or abusive: NSPCC Factsheet: August 2010 23. South Australian Department of Education (2010) Responding to Problem Sexual Behaviour Children and Young People. 24. Todd Kerry J (2006). Sexual Behaviour in Children. Is it Normal? Harbourview Centre for Sexual Assault and Traumatic Stress. 25. www.secasa.com.au The Centre for Sexual Assault South Metropolitan Region, Victoria: Appropriate Sexual Behaviour Guide. 26. Ryan G (2002), Childhood Sexuality: A Decade of Study, Part 1 – Research and Curriculum Development. Child Abuse and Neglect, Vol 24, No 1 pp33-48, Pergamon USA. 27. Brennan H, Graham J (2011), Is this Normal? Understanding Your Child’s Sexual Behaviour. Family Planning Queensland. 28. Gordon, B. N., & Schroeder, C. S. (1995). Sexuality: A developmental approach to problems. New York: Plenum Press. 29. Friedrich, W. N., Grambsch, P., Broughton, D., Kuiper, J., & Beilke, R. L. (1991). Normative sexual behavior in children. Pediatrics, 88, 456-464. 30. Macgregor. S (2008), Sex Offender Treatment Programs: Effectiveness of Prison and Community Based Programs in Australia and in New Zealand (Brief 3 April 2008). Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse Research Brief 31. Hall, D. H., Matthews, F., Pearce, J., Sarlo-McGarvey, N., & Gavin, D. (1996). The development of sexual behavior problems in children and youth. Ontario, Canada: Central Toronto Youth Services. 32. . www.communities.qld.gov.au/resources/childsafety The Department of Communities, Queensland: Positive and Protective: Identifying and Responding to Sexual Behaviours in Children and Young People. Facilitator Kit and Participant Workbook. 33. www.dhs.vic.gov.au The Department of Human Services Victoria: Problem sexual behaviour or sexually abusive behaviour, State Government: 2012. 34. www.stopitnow.org A community organisation that aims to stop child abuse in children by mobilising adults, families and communities to take action before harm is done: Prevention Tool; Guide Book; Factsheets 35. Neal SK, (2007), What is ‘normal sexual behaviour’ in children? 36. Government of Western Australia, Department of the Premier and Cabinet (2012). Western Australia Criminal Code Act Compilation Act 1913. 37. Fyson, Rachel (2007a). Young People with Learning Disabilities who Sexally Abuse: understanding, identifying and responding from within generic education and welfare services. Fyson, Rachel (2007b). Young People with Learning Disabilities who Sexually Harm Others: the role of criminal justice within a multi-agency response: Ann Craft Trust 38. Fyson, Rachel, Eadie, Tina and Cooke, Pam (2003). Adolescents with learning Disabilities who Show Sexually Inappropriate or Abuse Behaviours: Development of a Research Study. Child Abuse Review 12:305-314 39. Harlpen, C.T., Udry, J.R.,et al (1993). Testosterone and Pubertal Development as predictors of Sexual Activity: A panel analysis of adolescent males. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 436-447 40. Flannery, D.J. Rowe, D.C., & Gulley, B.L (1993). Impact of Pubertal Status, Timing and Age of Adolescent Sexual Experience and Delinquency. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8, 21-40. 41. Capaldi, D.M, Crosby, L., & Stoolmiller, M. (1997). Predicting the Timing of First Sexual Intercourse for Risk Adolescent Males. Child Development, 67, 344-359 42. Downing Jennifer & Bellis Mark (2009). Early Pubertal onset and its Relationship with Sexual Risk Taking, Substance Use and Anti-Social Behaviour: a preliminary cross sectional study. BMC Public Health, 9:446. 43. Bellis, MA, Downing, J. & Ashton, JA (2006). Adults at 12? Trends in Puberty and Their Public Health Consequences. Journal of Epidemiol Community Health, 60:910911. 44. Western Australian Government, Health Department (2009). Child Abuse Guidelines. 45. Faccini, L & Saide, MA (2012). “Can you breathe?” Autoerotic Asphyxiation and Asphxiophilia in a Person with an Intellectual Disability and Sex Offending. Sexuality and Disability 30:97-101 46. Dukes, E. & McGuire, BE. (2009). Enhancing Capacity to Make Sexuality Related Decisions in People with an Intellectual Disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53, (8):727-734. 47. McVilly, K. (2011)Impact, Effectiveness, and Future Application of Positive Behaviour Teams (PBTs) in the Provision of Disability Support Services in Western Australia: A research report. 48. Stalker, K & McArthur K. (2012). Child Abuse, Child Protection and Disabled Children: A review of recent research. Child Abuse Review 21:24-40 49. Kelly, G. & Parry, A. (2008). Managing Challenging Behaviour of People with Acquired Brain Injury in Community Settings: The first 7 years of specialist clinical service. Brain Impairment 9(3):293-304 50. WA Supreme Court (2011). Mental Health and the Judicial System. 51. Lindsay, WR. (2002).Research and literature on sex offenders with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 46 (1):74-85 52. Department of Attorney General WA (DoAG) (2009). 53. Ryan, G 91997). Sexually abusive youth: defining the population. Juvenile Sexual Offending; Cause, consequences, and correction (pp3-9) San Fransisco: Jossey Bass. 54. McLeod, S. A. (2008). Erik Erikson/Psychological Stages. Retrieved from www.simplypsychology.org/Erik-Erikson.html 55. Cockram. J (2005). Equal Justice? The experience and need of repeat offenders with intellectual disability in Western Australia. Retrieved from www.correctiveservies.wa.gov.au 56. Lindsay, W R. 2002. Research and literature on sex offenders with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 46 (1):74-85.