Here - Blue Stockings Society

advertisement

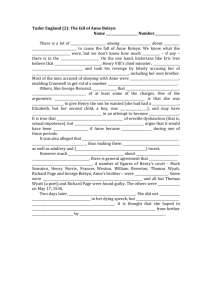

Jackson 1 Lauren Jackson Radical Women Sara Crosby 18th, April, 2014 The Radicalization and Martyrdom of Anne Boleyn? When first constructing this essay, I was questioned by a colleague who asked me what I was writing about. When I responded with Anne Boleyn, he exclaimed: “Oh! Isn’t she the whore?” To me this seemed to denote that women cannot have roles of power or influence, women cannot radicalize or attain modernity, but merely be influential in the ways of condemning sexuality. This paradigm surrounding Anne Boleyn has been accepted, promoted, and disseminated by the world at large for centuries. Anne Boleyn has been condemned as an adulteress and a witch. She has been subscribed with the actions of incest, and birthing monster fetuses. She has been proclaimed to have six fingers and to commit adultery with the King, her husband’s, closest friends and advisors. She was said to have been corrupt and to have destroyed her husband’s morality. Anne has been sensationalized in today’s market as well. She has been created as a product of sexual consumption, versus moral, religious, and artistic reformation. But a closer look at Anne’s history reveals a passionate woman with revolutionary ideas about religion, love, and education. Anne was advanced for her time and age, being a young girl born of a somewhat noble family in what is approximated to be the year 1501 in Norfolk, England. Her father, seeking patronage, sent Anne off to Margaret of Austria in 1513 to be one of her filles d’honneur. Margaret was serving as regent for her nephew Charles of Burgundy Jackson 2 who was busy with affairs regarding Spain. Anne adopted her mistress’s unique taste for illuminated manuscripts and patronage of the arts. For Anne would, in later years, collect expensive illuminated manuscripts and commission portraits of a somewhat controversial nature by Hans Holbein. Anne was the subject of much art, poetry, and story-telling. Being that Anne was a woman, it seems that what in a man might be viewed as a step towards modernity, was nothing more than witchcraft in a woman. In 1514, Anne was shipped off to France to serve Mary Tudor, a freshly made Queen of France, the sister to Anne’s future husband Henry Tudor (King Henry VIII), and was thenceforth groomed in the French manner. Mary Tudor’s French husband, King Phillip, died soon after their marriage, and Mary was sent back to England. Anne became the next queen’s – Claude -- lady-in-waiting. Anne and Claude had a close relationship, and this allowed Anne a very in depth knowledge to the ways of royalty due to her close confinement with Claude. Anne became self-sufficient, able to read and write in French and English, and had long refined her taste in arts and the patronage she would later endow. Anne had also become very fashionable during this time period, and on her return to England made quite a splash. Anne was considered saucy, fashionable, fiery, and forward in England. The French court had sustained a more modern establishment, especially in terms of lasciviousness. That is not to say there was no sensuality or adultery occurring in the English court, however it was more ‘under the surface’ than the French with an open mistress considered the maîtresse-en-titre, or exclusive mistress to the King of France. The English court was under the rule of Henry VIII and his Spanish Catholic bride Catherine of Aragon. In style were boxy, square shaped English hoods that covered Jackson 3 most of the hair of the female. Anne waltzed back into England sporting the French hood which is round and open and allows more freedom in styling the hair. Her dresses and sleeves were also considered more daring to the court at the time. And although it was not widely known yet, Anne had very strong ideas regarding religion, art, freedom of speech, education, justice, and philanthropy. Anne Boleyn was even conferred the title of Marquis, a title reserved only for men. This was an extremely radical action on Henry’s part, and showed that Anne had accomplished much to have earned it. Anne’s own father Thomas Boleyn and her brother George Boleyn, were both seen as something of reformists, if not quite radicals of the time, historian Joanna Denny claiming the Boleyns were in fact “reformists” (Denny, 112). Her father was friends with Erasmus, and exchanged intelligent communication on matters spiritual and temporal. Yet no one seems to cite Thomas or George as being anything but men of faith and learning insofar as they attempted to change the thinking of the time. George was later accused of incest with Anne, but the purpose of this was to smear Anne’s name and to claim she was a witch giving birth to a wicked fetus of monstrous shape and image being that it was the product of a union with her own natural brother. Thomas Boleyn escaped the scaffold entirely, despite his involvement in schemes and plots to maintain Boleyn power in the court. Anne’s own family advocated for change within what they considered mere ‘popery’ or false religion, thus she was ranged all round throughout her entire life with forward-thinking individuals, and those that she trusted most. Anne felt that Rome was a pit of evil and a product of riches garnered through charlatans. Anne has often been labeled a Protestant, although at the time it was Jackson 4 encompassed merely as Lutheranism, being that Martin Luther was the father of the movement after posting his Ninety-Five Theses. Lutheranism, or more broadly, Protestantism was a movement against the Catholic Church and the practices they felt were inherently wrong within the papacy. Corruption was rife in the church at this time, and this was dangerous considering the power that the church held within the state. Monarchs were essentially governed and dictated to by the Pope. The Pope was the individual, as ‘granted by God’, who could provide dispensations and absolutions to those who sought them. The Pope helped maintain peace throughout the world, helping to reach treaties and terms of compromise between warring nations. Monarchs presented themselves in supplication to the Pope in the hopes of gaining his favor, either in decisions, war, or marriage. Henry VIII was no exception to this line of pleading monarchs, and his loving wife Catherine of Aragon was a strict and devout Catholic woman. Anne was the direct antithesis of Catherine. Her manner of dress, speaking, and choice in religious thought were deeply opposed to what was deeply rooted in Catherine and her Catholic upbringing. The Obedience of a Christian Man by William Tyndale was a work that Anne had in her possession. This document was considered heretical, and Anne boldly presented a copy of the work to Henry. Historian Joanna Denny confirms: “Anne was in possession of Tyndale’s The Obedience of a Christian Man as soon as it was published in 1528. The Dean of the Chapel Royal, Richard Sampson, took it from her but she dared to go to the King in order to get it back, for it was ‘the dearest book that ever dean or cardinal took away’. She then persuaded Henry to read it, notably those passage she had marked with her nail, which was her habit” (Denny, 129). There was a certain Jackson 5 amount of threat to Anne involved in doing this simple action. Henry was a man whose emotions and opinions changed very swiftly. If he felt disobliged to thoroughly read the work Anne presented him, he could have had her arrested and charged. Instead, Anne applied to his ego, and dove into the heart of Tyndale’s work. According to Denny: “Anne believed she had been called like Esther, chosen from all other women by a great King ‘for such a time as this’ (Esther 4:14). At the King’s side, she could promote religious reform and her deeply held evangelical beliefs” (Denny, 129). When Henry finally tired of Anne and sought excuses to have her arrested, the issue of Tyndale’s work was brought to bear. But it seems that it wasn’t so much that the work The Obedience of a Christian Man was so heretical, as that it was considered to be coming from a Disobedient Christian Woman. If a man had presented Henry with the same work, might not history have looked on a little more kindly? For men executed at the time, namely Bishop Fisher, Thomas Wolsey, and Thomas More, Henry did not truly see them as condemned men, rather merely contrarily opposed to his viewpoints. He instead saw them as martyrs. But when Anne stood up for herself and her beliefs, she was brought to the forefront as a whore, never a martyr or a radical woman. Anne’s French upbringing may have had a tremendous amount of inspiration for the future she chose. Anne had a Bible available in English in her chambers for her ladies-in-waiting to peruse at their leisure. Historian Retha Warnicke confirms: “As the queen, Anne made accessible to her ladies an English translation of the Bible. This was probably Miles Coverdale’s version of 1535, the first complete Bible printed in English…” (Warnicke, 153). This was considered quite scandalous at the time, for the Catholic believed that the Word should only be spoken by a priest who was trained to Jackson 6 do so. The general public were not allowed access to Bibles in the vernacular or ‘common tongue’, but only the Catholic clergy could access Latin Bibles, which they read from and interpreted how they saw fit. This created a certain power alignment and stabilized the church’s position as the elite. For only God could speak through the clergy, and the clergy held great sway within the court. The Pope was de facto King of England at the time, ruling decisions through Henry. Henry was willful and longed to break free of the shackles of Rome with Anne’s help. Warnicke claims that Anne’s possession of an English bible: “…was not so radical an act as it might seem” (Warnicke, 153). However, it caused quite a stir in the court, and this was enough to turn voices against her and stir up contention. Historian David Starkey says: “Anne’s Scriptural readings were noticed and were, of course, intended to be noticed” (Starkey, 369). But Eric Ives implies it was more radical of an act: “Anne also defied established ecclesiastical authority by protecting the illegal trade in Bibles” (Ives, 269). Anne had a flair for French translated works as well, with Warnicke claiming: “Unquestionably, her beliefs also had reformist overtones. On at least one issue besides the schism, she broke with English tradition, for she had long been reading the scriptures in French and continued to receive copies of divine books in this language after her marriage. Thus she asked William Locke, the king’s mercer, when he went on his buying trips to the continent to obtain for her in French the gospels, epistles, and Psalms…” (Warnicke, 153). Starkey confirms this: “…’that I have heard my father say that when he was a young merchant and used to go by the sea…Anne Boleyn…caused him to get her the Gospels and Epistles written in parchment in French together with the Psalms” (Starkey, 370). Jackson 7 Through the perusal of Tyndale’s work, various tracts, and constant murmurings in his ear by Anne, Henry soon found himself sending out his most trusted advisors on a Special Matter. This matter was his divorce from his wife Catherine of Aragon. The Pope would not grant a dispensation, and Henry longed to marry Anne. Thus to gain his way, Henry broke from the Church of Rome and established the new Church of England. Henry had only ever known Catholicism, but Anne and her Lutheran views helped create a new religion, tethered to the old. Historian Joanna Denny expounds with what was dubbed the “Oxford Scandal” wherein the college was attacked for ‘the secret sowing and setting forth of Lutheran heresies’: “The ‘Oxford scandal’ of 1528 reveals Anne’s support for the new wave of evangelical scholars whom Wolsey and the Church establishment regarded as dangerous and heretical” (Denny, 127). Bibles and Tyndale were not the only radical things Anne accomplished with the written word. Denny provides evidence that Anne was not only one to read the tracts that were issued, but to help transport them illegally. While Anne was in France, she had access to books that were banned in England: “When she returned she kept her contacts and obtained many new evangelical works through underground channels and networks” (Denny, 128), and Anne’s library was quite extensive and diverse: “Anne owned the Epistle and Gospel for the Fifty-two Sundays in the Year and Le Pasteur Evangelique (The Good Shepherd) by the anti-establishment and reformist poet Clement Marot” (Denny, 128). Starkey shows that Anne also had: “One is Anne’s splendidly illuminated Psalter. It is decorated with Anne’s arms, badges and mottoes, and gives the text of the Psalms in a new, radical French translation probably by Lefevre’s disciple, Louis de Berquin, who was burned for heresy in 1529. Another is Jackson 8 Anne’s French Bible, in Lefevre’s own translation” (Starkey, 370-371). Starkey makes vividly clear the danger Anne was putting herself in: “This trade in foreign religious books was illegal” (Starkey, 371). Anne’s brother George began presenting banned books to Anne himself with dedications to her, as well as using his diplomatic missions to France to smuggle banned books back to England. Anne was set to not only collect these books for herself, but to make sure they were distributed. Anne also rescued those who were sentenced or arrested. Denny says of Anne’s sources: “William Locke and Richard Herman in Antwerp were among those who supplied books for her. Thomas Always, prosecuted by Wolsey for having banned books, wrote to Anne: ‘I remembered how many deeds of pity your goodness has done within these few years…without respect of any persons, as well as to strangers and aliens as to many of this land, as well to poor as to rich” (Denny, 128). On top of Anne’s reformist nature, she was not discriminatory in her power. She gave to those who needed, and assisted those who asked. She did not retaliate in the ways she saw the Catholic Church doing, by favoring only the wealthy. And Starkey claims that by attempting to free prisoners and write letters to Wolsey and other members of the court for help she had “…dared to reveal her hand as a patroness of dissent” (Starkey, 375). Anne also protected and rescued those who spoke out against the Catholic Church. Denny explains: “Anne now took the opportunity of her growing influence to save some of the evangelical network from arrest, torture and even death. She influenced the King to write to Wolsey on behalf of another victim of the heresy laws, the Prior of Reading, who had been seized with Forman for possessing Lutheran books” (Denny, 127). Especially in the case of Nicholas Bourbon, who according to Warnicke: Jackson 9 “Early in 1534, after he had attacked the Roman Catholic ‘cult’ of saints of his Church, Bourbon had been forced to flee into exile. Upon his arrival in England he had entered the household of William Butts, the king’s physician, who contacted Anne about employing the refugee as a schoolmaster to her ward” (Warnicke, 148). Thus not only was Anne one to speak out against that which was oppressive, but she helped those who risked themselves as well. Latimer recorded the event of Bourbon thus: “Dr Butts receiving letters out of France from one Nicholas Borbonius, a learned young man, and very zealous in the scriptures, declaring his imprisonment in his own country for that he had uttered certain talk in the derogation of the bishop of Rome and his usurped authority, made his suit to Anne…in his behalf, did not only obtain by her grace’s means the King’s letters for his delivery but also after he was come into England his whole maintenance at her expense…only charges in the house of the said Mr Butts” (Denny, 127). Denny offers information on others that Anne assisted: “Anne’s chaplain, William Latimer, records that she supported a French refugee, Mrs Marye, who ‘fled out of France into England for religion’. Anne also wanted the scholar John Sturmius to come from Paris and sponsored Tyndale’s forbidden New Testament” (Denny, 128). Anne also helped to promote those that shared her beliefs and viewpoints. It is interesting because historian Retha Warnicke goes back and forth with how much power she attributes to Anne. Warnicke also holds to the beliefs of Anne’s whoredom. Anne rescued many from disastrous fates for being radical. Denny says: “Anne ‘was a special comforter and aider of all the professors of Christ’s gospel’. The Imperial ambassador was to state that the Boleyns were the ‘principal instruments’ of rescuing ‘heretics’ from prison and that Anne was ‘the principal cause of the spread of Jackson 10 Lutheranism in his country’, which made her the enemy of the Catholic Church” (Denny, 127). Historian Eric Ives chimes in on this note: “We have seen how Anne played a major part in pushing Henry into asserting his headship of the Church. That headship was not just a constitutional rejection of the primacy of Rome. It was, as Thomas More and others at the time were well aware, a change with profound implications, revolutionizing the ethos of Christianity in England” (Ives, 260). No small feat for Anne Boleyn, and no small triumph either. Anne was especially blamed, as a woman and a seducer. Ives explains: “Catholic hatred of Anne damned her for the break with Rome and for the entrance of heresy into England. It was right on both counts” (Ives, 261). Anne believed in education and was lauded by William Latimer as: “…a favorer of good letters and learning…” (Warnicke, 150), and: “…attempted to assist the universities. During her first year as queen she gave forty pounds to Cambridge and Oxford and thereafter eighty pounds to each” (Warnicke, 151). This was not all, for Anne assisted in aiding poor students and scholars who often were reduced to begging and borrowing. Anne sponsored students through university and monks as well who were obtaining their bachelors of divinity. Anne firmly believed in higher education and the bettering of oneself, a rather modern notion, especially for a woman of the time period. Historian Joanna Denny takes Anne’s role one step further: “Together with the great preacher Hugh Latimer, many Cambridge scholars were favored by Anne and later promoted to positions where they could influence the advance of the reform religion” (Denny, 127). Anne found it within her power to appoint several positions within the court and the church, and also her own household, to those that held similar views to her. Their Jackson 11 religious alignment was also obvious; Anne needed people in her corner to maintain her power and position. But Warnicke suggests that Anne was not capable of such a feat: “To suggest that Anne alone had won for these men either the bishoprics or sufficiently advanced positions in the Church that made their subsequent episcopal election possible would be to exaggerate greatly her influence in religious matters” (Warnicke, 156). Which is interesting because Warnicke condemns Anne over and over for her evil power that she wielded and that ultimately resulted in her execution. Anne’s power for manipulation and seduction, and the ability to climb her way viciously through the court, rescue those from prison, transport illegal books, but not find a position for someone with aligning viewpoints. Eric Ives refutes Warnicke’s statement by saying: “Anne’s religious patronage extended to lesser positions in the Church as well” (Ives, 261). Historians have long agreed that Anne was able to help appoint Thomas Cromwell and assist in his meteoric rise through the court, along with her father and brother’s help, yet Warnicke claims otherwise. Warnicke also claims that there was no faction formed between the Boleyn’s and Cromwell, despite various schemes comprised between the two of them: “Even more important to the argument that they did not form a faction with a well-developed religious policy is that Cromwell was a more radical reformer than Anne” (Warnicke, 159). It is interesting to note that Cromwell aligned himself with those who were against the divorce. A man of the time being against divorce, one fails to see where radicalism shows itself. Anne Boleyn was not submissive. She was bold and stood up for what she believed in. But this is seen as nothing more than a wayward woman, rather than a bold reformist. Simply because she was considered ‘sexual’ her reformist reviews are Jackson 12 meaningless? Just because she’s a woman? Perhaps because she didn’t maintain her quiet submissive role? Some believe it was selfish reasons that caused her to help Henry break with Rome, yet she had strong personal beliefs that had been nurtured by her family for years, thus this argument seems to fall flat. Joanna Denny seems to voice Anne’s radicalism best: “Anne Boleyn was the catalyst for the Reformation, the initiator of the Protestant religion in England. The religious controversies of her day were Anne’s motivation and driving force. Anne ‘lived for one thing: to see the Reformed religion overcome the opposition to it both within the Church and outside it….she ached to see the Reformation triumph’” (Denny, 132). Anne sparked a fire that would ultimately cost her life. Members of the court and her own husband accused her of atrocious acts and undertakings, all because of the power she had attained. Henry put her aside for her lack of bearing him a male child, but the court put her aside because they were terrified of all she was achieving and all that she represented. Anne may not have been executed for her beliefs, but she stood for was executed as much as her body. Her flames are still being fanned, and her reforms are still in place. A woman’s mind is a dangerous tool when levelled against those in power with true reform. For only those who are underrepresented or oppressed can revolt and rise above. Only a true radical could make changes that would have lasted for the last five centuries. Jackson 13 Works Cited: Denny, Joanna. Anne Boleyn. London: Piatkus Books, 2004. Print. Ives, Eric. The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn. Cornwall: Blackwell Publishing, 2004. Print. Ridgway, Claire. The Anne Boleyn Collection. United Kingdom: Made Global Publishing, 2012. Print. Starkey, David. Six Wives – the Queens of Henry VIII. New York: HarperCollins, 2003. Print. Warnicke, Retha. The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. Print. Weir, Alison. The Lady in the Tower. London: Random House, 2009. Print.