Airway management in head injury

advertisement

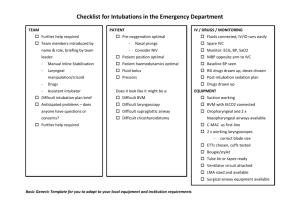

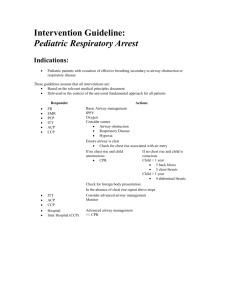

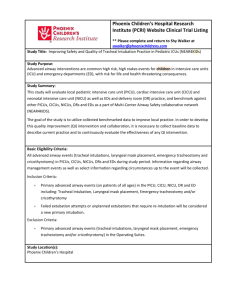

Airway Management in Head Injury Katy Talbot Scenario A 32 year old female has suffered a head injury whilst jumping her horse. It was a rotational fall, where the horse landed on top of her. On initial assessment she has a GCS of 6. A – Gurgling noises heard B – RR 23, sats 94% OA C – CRT<2sec, pulse 95, BP 126/84 D – left pupil dilated and not reacting to light How would you assess her airway? How would you manage her airway? What other considerations are there? ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ Primary & Secondary Head Injury Primary – The initial injury caused by the trauma, due to displacement of brain structures within the skull. Secondary – Global neurone damage which is not directly caused by the injury, and occurs some time after the incident. It may or may not be a complication of the injury itself, and is accountable for most cases that deteriorate after the initial injury. Examples: Hypoxia Hypercapnia Ischaemia Oedema Herniation of brain structures Acidosis Excitotoxicity – neural cell death by apoptosis due to excess glutamate in the extracellular space Diagnosing the Inadequate Airway Risk factors – Altered consciousness, direct injury to the airway, inhalation injury, and severe wounds/massive haemorrhage. Signs to look for: LOOK – Use of accessory muscles, agitation, cyanosis, asymmetrical chest wall movement, tachypnoea, drooling. LISTEN – Failed attempts to speak, abnormal breath sounds e.g. snoring, gurgling, stridor, crackles, reduced breath sounds. FEEL – Tracheal Deviation, subcutaneous emphysema. Trauma patients have a compromised airway until proven otherwise. Any of the above signs require active airway management. Once the inadequate airway is identified options include: 1) Simple airway strategies – jaw thrust & oxygen mask (not head tilt & chin lift!) 2) Definitive airway. Mask Ventilation It may be difficult to sufficiently oxygenate some people with a facial mask. Risk factors can be remembered by the pneumonic BONES. B – beard O – obesity N – no teeth E – elderly (age>55) S – snoring C – Spine Control While managing the airway the best management of the cervical spine is manual-in-line stabilisation. When compared with rigid neck collar and spinal board strapping, manual control provided a better view of the glottis without compromising C-spine protection. Indications for Definitive Airway 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Presence of apnoea. Need for airway protection form aspiration: vomitus, bleeding. Unconsciousness: Glasgow Coma Scale <8. Severe facio-maxillary fractures. Risk for obstruction: neck haematoma, laryngeal/tracheal injury. Impending or potential airway compromise: inhalation injury. Inability to maintain SpO2> 90% by facemask oxygenation. A definitive airway is defined as a cuffed tube below the larynx. It allows complete control of the airway, and protects from aspiration of gastric contents. It can be an endotracheal tube, or a surgical airway. Rapid Sequence Induction Should be carried out in the presence of somebody who is trained to perform a surgical airway if needed. Pre-oxygenation. Sellick’s manoeuvre – cricoid pressure to prevent aspiration of gastric contents. Short acting anaesthetic agent – etomidate Muscle relaxant – succinycholine Check correct placement of ET tube – auscultation, CO2 detection in exhaled air. Surgical Airway Needed in cases where there is severe glottis oedema, oropharyngeal haemorrhage, or laryngeal fracture. It is also needed if intubation fails. Cricothyrotomy can be performed in two ways: 1) 12-14 gauge cannula 2) Incision of the cricothyroid membrane, and insertion of cuffed tube into the trachea Percutaneous tracheostomy should not be used in the trauma setting, due to the need to extend the cervical spine. Semi-Definitive Airway These are used as temporary airways if initial intubation is unsuccessful. Oral adjuncts – Guedel airway Safe to use in head trauma with oxygenation via a mask Nasopharyngeal airways must NEVER be used in head injury. In basal skull fractures nasopharyngeal airways can perforate the cranium and cause further penetrative brain injury. Laryngeal mask/tube Not definitive airway, but is a good stop-gap, and can be used without direct visualisation of the vocal cords, and without manipulation of the cervical spine.