Red Cells web story - Red Blood Cell Laboratory

advertisement

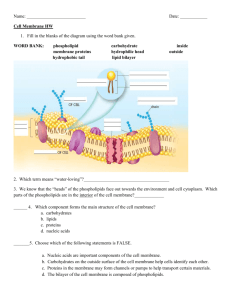

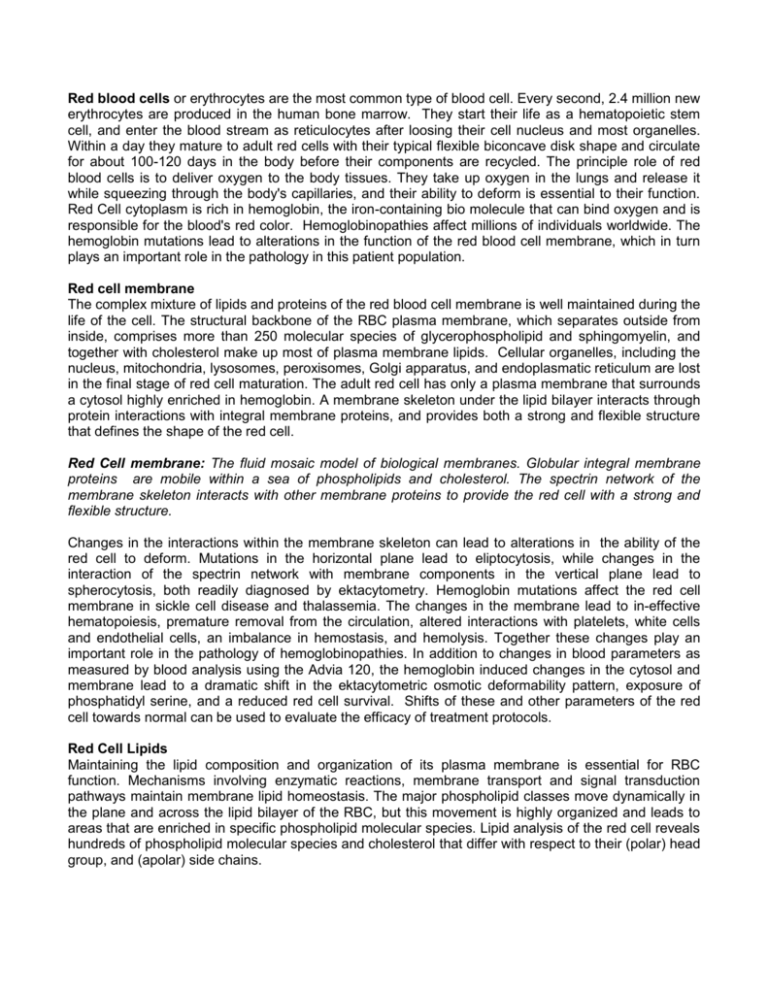

Red blood cells or erythrocytes are the most common type of blood cell. Every second, 2.4 million new erythrocytes are produced in the human bone marrow. They start their life as a hematopoietic stem cell, and enter the blood stream as reticulocytes after loosing their cell nucleus and most organelles. Within a day they mature to adult red cells with their typical flexible biconcave disk shape and circulate for about 100-120 days in the body before their components are recycled. The principle role of red blood cells is to deliver oxygen to the body tissues. They take up oxygen in the lungs and release it while squeezing through the body's capillaries, and their ability to deform is essential to their function. Red Cell cytoplasm is rich in hemoglobin, the iron-containing bio molecule that can bind oxygen and is responsible for the blood's red color. Hemoglobinopathies affect millions of individuals worldwide. The hemoglobin mutations lead to alterations in the function of the red blood cell membrane, which in turn plays an important role in the pathology in this patient population. Red cell membrane The complex mixture of lipids and proteins of the red blood cell membrane is well maintained during the life of the cell. The structural backbone of the RBC plasma membrane, which separates outside from inside, comprises more than 250 molecular species of glycerophospholipid and sphingomyelin, and together with cholesterol make up most of plasma membrane lipids. Cellular organelles, including the nucleus, mitochondria, lysosomes, peroxisomes, Golgi apparatus, and endoplasmatic reticulum are lost in the final stage of red cell maturation. The adult red cell has only a plasma membrane that surrounds a cytosol highly enriched in hemoglobin. A membrane skeleton under the lipid bilayer interacts through protein interactions with integral membrane proteins, and provides both a strong and flexible structure that defines the shape of the red cell. Red Cell membrane: The fluid mosaic model of biological membranes. Globular integral membrane proteins are mobile within a sea of phospholipids and cholesterol. The spectrin network of the membrane skeleton interacts with other membrane proteins to provide the red cell with a strong and flexible structure. Changes in the interactions within the membrane skeleton can lead to alterations in the ability of the red cell to deform. Mutations in the horizontal plane lead to eliptocytosis, while changes in the interaction of the spectrin network with membrane components in the vertical plane lead to spherocytosis, both readily diagnosed by ektacytometry. Hemoglobin mutations affect the red cell membrane in sickle cell disease and thalassemia. The changes in the membrane lead to in-effective hematopoiesis, premature removal from the circulation, altered interactions with platelets, white cells and endothelial cells, an imbalance in hemostasis, and hemolysis. Together these changes play an important role in the pathology of hemoglobinopathies. In addition to changes in blood parameters as measured by blood analysis using the Advia 120, the hemoglobin induced changes in the cytosol and membrane lead to a dramatic shift in the ektacytometric osmotic deformability pattern, exposure of phosphatidyl serine, and a reduced red cell survival. Shifts of these and other parameters of the red cell towards normal can be used to evaluate the efficacy of treatment protocols. Red Cell Lipids Maintaining the lipid composition and organization of its plasma membrane is essential for RBC function. Mechanisms involving enzymatic reactions, membrane transport and signal transduction pathways maintain membrane lipid homeostasis. The major phospholipid classes move dynamically in the plane and across the lipid bilayer of the RBC, but this movement is highly organized and leads to areas that are enriched in specific phospholipid molecular species. Lipid analysis of the red cell reveals hundreds of phospholipid molecular species and cholesterol that differ with respect to their (polar) head group, and (apolar) side chains. RBC phospholipid molecular species All phospholipids have a polar, hydrophylic headgroup, and non-polar hydrophobic hydrocarbon tails. Glycerophospholipids are characterized by their glycerol backbone. In sphingomyelin, the backbone is sphingosine. Long carbon chains connected to the first and second carbon of glycerol provide the hydrophobic part of the molecule. The phosphate and additional headgroup structure provide the hydrophilic portion of the molecule. This variety in lipid structures accommodates proper packing of lipids in the bilayer and governs protein-lipid interactions. The molecular species composition of the lipids is well maintained during the life of the RBC, and alterations will lead to a dysfunction of the membrane and a loss of cellular viability. The lipid bilayer in which proteins are embedded, together with the underlying membrane skeleton provide a strong and flexible membrane for the RBC to perform its tasks in the circulation. The organization of the complex mixture of lipid molecules is highly dynamic. The lipids move rapidly in the plane of the bilayer, but this movement is not a random process. Certain lipid species and proteins will aggregate in domains in the membrane. These micro domains, also called “rafts”, have important functions as they will organize membrane components into local communities that are involved in specific physiologic processes such as signal transduction. In these localized areas, components of these pathways are aggregated to act in concert. Red Cell lipids are synthesized de novo during the early stages of erythropoiesis, to form the membranes that surround the cell as well as the cellular organels. In the adult red cell, oxidatively damaged fatty acyl chains are removed and selectively replaced to maintain a proper membrane composition. Maintenance of phospholipid organization in RBC. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) will modify the unsaturated fatty acyl side chains in phospholipids (PL). The oxidized lipids (oxPL) will have a different orientation in the bilayer and are recognized by phospholipases (PLA2) that remove the oxidized fatty acid to generate lysophospholipid (LPL). Fatty acid (FA) taken up from plasma is activated to fatty acyl CoA (FA-CoA) by acylCoA synthetase (ACSL6) using ATP and Coenzyme A (CoA). FA-CoA pools are modulated by FA-CoA binding protein (FA-CoABP). Lysophospholipid acylCoA acyltransferases (LPLAT) use FA-CoA and LPL to generate PL, completing the de-acylation/re-acylation repair cycle. In addition to the heterogeneous, dynamic and highly organized lipid distribution in the plane of the bilayer, phospholipids also transfer from the outer to the inner monolayer and back. The rate of this flipflop across the membrane is different for lipids with different headgroups and levels of unsaturation. Moreover, the movement is not random and is orchestrated by proteins in the bilayer as well as factors in the cytosol. In steady state, the choline containing phospholipids PC and sphingomyelin (SM) are mainly found in the outer monolayer, while the amino phospholipids are predominantly (PE) or exclusively (PS) found in the inner monolayer. This highly asymmetric plasma membrane distribution is typical for most mammalian cells. A loss of this asymmetry, and in particular the exposure of PS on the surface of the cell is an early event in apoptosis and will lead to the recognition and removal of cells by macrophages. The red cell membrane bilayer. Phospholipid molecular species move rapidly in the plane, as well as across the bilayer in a dynamic but highly organized fashion. Areas are enriched in certain lipids essential for proper protein function and phospholipids are asymmetrically distributed across the lipid bilayer with the amino phospholipids (PS and PE) on the inside and choline containing phospholipids (PC and SM) on the outside. The asymmetric distribution of phospholipids across the bilayer is maintained by the Magnesium ATP dependent aminophospholipidtranslocase or flippase, which transfers PS and PE from outer to inner monolayer at the expense of ATP. Loss of phospholipid asymmetry and the exposure of PS is triggered by a phospholipid scrambling activity. Membrane lipids in hemoglobinopathies The phospholipid molecular species organization highly maintained during the life of the RBC, is under high stress in hemoglobinopathies. The increased oxidant stress and observed damage to the lipids suggests that phospholipid repair is not efficient enough to maintain the proper molecular species composition in these cells. The differences in molecular species composition of density fractionated sickle red blood cells point at a process in which the repair system is affected differently in individual cells or cell populations. All RBCs are exposed to the same pool of fatty acid substrates (plasma). Therefore the difference seems to be related to the activity of the enzymes that use this pool for phospholipid repair. The RBC is not able to replace proteins when they are irreversibly damaged by reactive oxygen species. Since several proteins are involved in the lipid repair process, damage of any of these may affect their proper function. The recently identified LPCAT activity, which exhibits an EFhand motifs at the C-terminus, was modulated by Calcium and Magnesium. Since both cytosolic calcium and oxidant stress are altered in subpopulations of sickle RBCs this suggests that lipid repair is modulated differently in subpopulations of sickle red cells. Together, oxidant stress and alterations in RBC cytosol in hemoglobinopathy RBCs will lead to the inability to maintain a proper lipid composition, which in turn may lead to alterations in membrane function, including ion and water transport across the bilayer and altered RBC density distributions PS exposure in hemoglobinopathies Exposure of PS on subpopulations of red blood cells has been reported in Sickle Cell disease and Thalassemia, and is important in the pathology of the disease. In these PS exposing red blood cells the flippase is deactivated and phospholipid scrambling is increased, and both oxidant stress and elevated cytosolic calcium seem to play a role in this process. The percentage of PS exposing RBCs in hemoglobinopathies seems low (a few percent), but given the large number of red blood cells in the circulation, even a low number of PS exposing red blood cells provides a significant surface of PS exposing membrane. PS exposing cells are recognized and removed from the circulation, and the loss of phospholipid asymmetry is involved in the reduced red blood cell lifespan. In addition, exposure of PS during erythropoiesis, an early step in apoptosis, plays an important role in the ineffective erythropoiesis, particularly evident in thalassemia. The inability of red blood cells or red blood cell precursors to maintain phospholipid asymmetry therefore plays a role in the anemia. As PS exposure is a trigger for removal, their presence in the circulation suggests a high rate of generation of such cells that is not compensated by efficient removal, which may be related to inefficient spleen function. When PS exposing red blood cells are not readily removed, they can induce pathophysiology responses such as imbalanced hemostasis. As indicated, activated platelets expose PS on their surface as a normal step in hemostasis. Given the relative number of red blood cells as compared to platelets in the circulation, even a low number of PS exposing RBCs can lead to an imbalance in hemostasis. The loss of red blood cells phospholipid asymmetry has been correlated with the prothrombotic state in hemoglobinopathies. PS exposure alters the interactions of red blood cells with other blood cells and with endothelial cells of the vascular wall and may relate to vaso-occlusive crisis in sickle cell disease. PS exposing RBCs also become targets for phospholipases. The baseline levels of secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) an important lipid mediator in inflammation is elevated in SCD patients. sPLA2 does not break down normal RBCs, but will hydrolyze lipids in PS exposing RBCs leading to hemolysis. This in turn may be the underlying reason for the elevated levels of LDH, plasma free Hb and arginase all reported to have an important role in sickle cell pathology. In addition to hemolysis, sPLA2 hydrolysis will generate lysophospholipids and free fatty acids, including arachidonic acid, important building blocks for thromboxanes and leukotrienes. Excessive amounts of both fatty acids and lysophospholipids can have profound effects on the vasculature. Measuring levels of sPLA2 has shown to be predictive for the onset of acute chest syndrome (ACS) in sickle cell patients. Intervention based on this level has allowed the prevention of this devastating syndrome and the major cause of death in this patient population. Together these data suggest that the inflammatory increase of sPLA 2 may not only predict ACS but also play a role in the observed vascular damage. In summary, the mutations in the globin genes that underlie hemoglobinopathies have profound effects on red blood cell membranes. A better understanding of the key proteins involved in the maintenance of membrane composition and organization is essential to evaluate the differences in RBC membrane abnormalities observed between different patients. While genomic variations in the key enzymes are noted, no link has been made with clinical manifestations. The loss of normal lipid composition and organization during erythropoiesis or the life of the cell in the circulation leads to altered interactions with other blood cells and plasma components that play a role in the pathology that defines these red blood cells disorders. Red Cell Metabolism From Beutler