Marine Habitats - Living Islands

advertisement

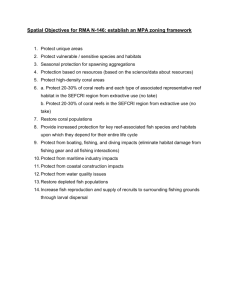

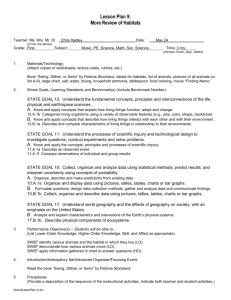

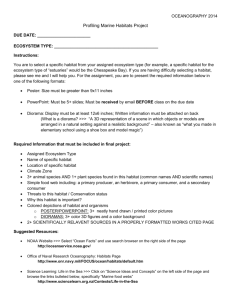

Lesson Development and Presentation Guide Marine Habitats Created through the Environmental Education Initiative Pilot Project By: Carter Daniel, Jake Shimkus, A.J. Alik, and Darren Joji This lesson guide was created in a collaborative effort between Living Islands 501c(3) and the Marshall Islands Conservation Society (MICS) in 2015. Distributed in part by the Republic of the Marshall Islands Environmental Protection Authority (RMI-EPA) This lesson was created in part by Carter Daniel, Jake Shimkus, A.J. Alik, and Darren Joji as members of the design team. Special thanks to Mark Stege of MICS, Moriana Phillip of RMI-EPA, and the administrators of Co-Op, Assumption, Rita, and Delap Elementary Schools for their contributions and support. All parts of this lesson guide may be reproduced and replicated in any form, electronic or otherwise, for free distribution and use by any party. Dissemination of this material is encouraged. For more information regarding the Environmental Education Initiative, or the efforts of Living Islands 501c(3), MICS, or RMI-EPA please contact the following: Living Islands 501c(3): kianna@livingislands.org MICS: mics@cmi.edu RMI-EPA: morianaphilips@gmail.com 1 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 The following is a lesson plan designed through the Environmental Education Initiative (EEI). The EEI began as a collaborative effort of Living Islands and MICS as a means for engaging college students and community experts in the design of relevant, hands-on lessons for environmental education in the Marshall Islands. The EEI is today operated by the RMI EPA as an extension of its Clean Schools Initiative. These lessons are rooted in the results of extended student surveys, designed to gather an understanding of current elementary-age student knowledge on environmental conservation. The key learning objectives are built upon these survey results. The design of the lesson follows the Madeline Hunter lesson planning model to ensure a deep understanding of the key learning objectives is achieved. Key to each lesson is the hands-on activity element. Based on conclusive research that students learn best when physically active, these lessons focus on getting students engaged in each topic through movement, while focusing on the key learning objectives. This packet presents not only the lesson outline, but also the survey results and the process involved in building the lesson that resulted. The lesson below was originally presented by a team of students and experts to elementary kids grades 4-6. It is specifically designed to be conducted with little-to-no outside materials, and to be as applicable as possible to communities throughout the RMI. However, some major differences are present in every community. Therefore, a set of customization instructions are available at the end of this packet to enable educators to tailor this lesson to the specific context of their classroom. 2 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Table of Contents: Student Surveys: Survey Process Questions Questions Review Survey Results 4 4 5 6 Lesson Design: Objectives Vocabulary Activity 7 7 8 Lesson Outline: Overview Introduction Activity 1 Objectives Review Presentation Group Review Activity 2 Independent Review 9 9 10 11 12 13 13 14 Program customization: Process Reviewing Models Reviewing Vocabulary Checking Activities and Resources Checking Current Understanding Incorporation and Recording 15 16 16 17 18 18 3 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Student Surveys: A simple survey was conducted to gather an understanding of current student knowledge on the relevant topics for this lesson. The following reviews the process of that survey, the results and the general conclusions that can be drawn from the responses. Survey Process: Before starting the survey, the general topic was selected for its relevance to life in the RMI and applicability to younger students. From there, specific teachable items are listed as a way of breaking the general topic down into more specified fields. For example, for the topic of resource use, specific topics included fisheries, land use, crop growth, etc. These more specific focus areas then serve as the basis for the actual lesson design. By focusing on just one or two of these more narrow sub-topics, potential lesson objectives can then be identified. If teaching about fisheries, one could help to teach students about how to maintain fish populations, what practices are most effective for sustainable fishing, what other activities other than fishing effect fish populations, etc. These possible lesson objectives are then ranked according to their relevance, viability, and availability of relevant expertise. The top three of these objectives are then translated into questions for the student survey. The goal is to understand to what extent students already have mastered the proposed outcomes of the lesson, and therefore at what level the lesson should be taught. Designing these questions requires that both the desire of the surveyor and the possible answers are kept in mind. While questions must necessarily be open ended to prevent leading questions, their phrasing and context are often very important to ensure that usable responses are available. By developing a general hypothesis of what student responses might be for each question, the design of each question is then able to be tailored to test that particular hypothesis. Once the questions have been designed, surveyors are brought in for a brief training on survey technique and etiquette. It is crucial that every student is aware of why they are being asked the questions, and that they are in no way being tested. It is also important to encourage them to find an answer, but acknowledge that saying “I don’t know” is perfectly acceptable as well. Surveyors are cautioned in providing additional information not to create a leading question, and how to faithfully record students’ answers. These results are then recorded by each surveyor through one-on-one interviews with students. Questions: What is a habitat? What will happen if there are no habitats left? Why do so many fish live near coral reefs? What do fish eat? 4 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Questions Review: These questions generally aim to gain an understanding of how nuanced students’ understandings are of the natural world. Most of these questions ask students to picture certain elements of marine habitats to better understand exactly what these mental images look like, and how that can be used in developing effective lessons. The question “what is a habitat?” is almost entirely a question of vocabulary. As a fundamental part of discussing habitat and ecosystem services, the word habitat must be understood for that discussion to be effective. Students’ responses to this question would help to determine to what extent that vocabulary word itself had to be focused on in a lesson, and at what grade level the lesson ought to be introduced to be most effective. This also informs the basis for the first objective of the lesson: helping students understand and conceptualize exactly what a habitat is. The question “what will happen if there are no habitats left?” asked students to imagine what would happen if there were no more places for animals to live. Anticipating responses that involved the animals dying or leaving, this question aimed to capture the degree to which students understand the critical relationship between animals and their habitats, building the foundation for the objective of students understanding why marine habitats are so important not only to animals but to life in the Marshall Islands overall. The question “why do so many fish live near coral reefs?” again asked students to look at the relationship between animal and habitat, this time applied specifically to coral reefs. This question anticipated students providing responses that involved the various ecosystem services provided to fish by coral reefs, to understand how familiar students are with the different necessities a habitat provides. This will also build the foundation for the objective of understanding the importance of habitats. The question “what do fish eat?” was aimed at the specific understanding of what fish need to survive. If students have a more nuanced understanding of what other animals need to survive, then explaining the ways that humans can disrupt these delicate balances, or correct existing issues, may be easier. 5 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Survey Results: To better inform instructors, the following were the results of the survey conducted in 2015. Instructors should take note of those answers most common and the gaps of understanding present in the survey results. These may help to inform the way that the materials included in this packet are presented to students. What is a habitat? A place where animals live A place where people live “A place to live” No response - 19% 8% 8% 58% What will happen if there are no habitats left? Animals will die “Death” or simply “die” Humans will die There will be no food left No response - 22% 17% 11% 11% 13% Why do so many fish live near coral reefs? Food Hid from other fish It is their home / the live there For shelter / protection No response - 44% 20% 17% 17% 34% What do fish eat? Other fish Seaweed / sea grass Crabs Sand No Response - 35% 22% 10% 7% 9% 6 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Lesson Design: The following is a brief review of the thought process behind designing the lesson included below. This is rooted in the results of the survey as well as the selected learning objectives of the team and interest expressed by the participants. Objectives: Four objectives were selected for the lesson: Students will be able to… - Explain and give examples of habitat - Tell the importance of coral and the marine habitat - Recall the value of marine habitats to Marshallese society - Give example of how to conserve and protect habitats The first objective comes directly from the overall lack of understanding of the concept of habitats expressed in the survey. With 58% of students having no concept of habitats, this particular objective clearly needed to be the central focus of the lesson. The second and third objectives serve as motivators in the lesson. In order to motivate action on conservation, it is crucial to develop an understanding of the importance of habitats to both the animals who live there, and people on the islands. From our survey, it was clear that a general understanding of the implications of habitat destruction is already present. Many students expressed that “death” or a lack of food would result from habitat destruction. These objectives are therefore present to reinforce existing knowledge and build appropriate ideas of the results of habitat destruction and conservation. The fourth objective is the ultimate outcome of the lesson. The desire is for students to walk away with a complete understanding of what they can do to help their environment. Building on the demonstrated knowledge of the consequences of habitat destruction, this objective focuses learning around positive, and constructive actions students can take to make a difference. Vocabulary: Five key vocabulary terms were selected for the lesson: - Habitat - Coral Reef - Habitat Destruction - Herbivore Fish - Dredging The term habitat is a central vocabulary term here for its critical importance to the overall lesson, and the demonstrated lack of understanding of this terminology from our survey. Most importantly, it is crucial for students to understand what services a habitat provides (shelter and food among others). From the survey it is clear that students have some understanding that coral reef habitats provide food and shelter for fish, and solidifying this understanding will be critical to this lesson. 7 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 The term coral reef is explicitly explained in the lesson as it is the primary example of a marine habitat here in the Marshall Islands. Students did reference coral reefs throughout our survey. Connecting that understanding to the discussion will therefore build on existing knowledge. The term habitat destruction is explained on its own in the lesson as a way of clearly building student knowledge of the idea of destruction as it is opposed to conservation. The survey did not clarify students’ understanding of what kinds of actions lead to habitat destruction, so explaining this concept with examples is of critical importance. The term herbivore fish is explained here as a way of helping students to understand how disrupting the balance in a habitat can lead to its destruction. Herbivore fish take care of coral reefs by eating algae off the corals. If too many are taken out by fishermen, the algae takes over and destroys the reef. Helping students to understand that disrupting herbivore fish and the balances they maintain is a very valuable piece. Dredging is also explained in this lesson as it is a very visual form of habitat destruction, but also has its purposes. The term dredging is often used in modern discussions, and helping students to understand the term will prepare them to contribute to informed discussions. Activity: The activity is designed to be the focal point of the lesson. It is both the motivator for the lesson itself, providing a visual and tactile experience of habitat destruction for students, as well as a constructive method for empowering students at the end of the lesson. In general, the vague responses offered by the survey make it clear that students do not understand the full implications of habitat destruction. The activity is designed to allow instructors ample space and time to explain these relationships as they go along. After every round of the game, instructors either pull out or add back a chair, representing a habitat. At this time, they also discuss with students what that chair represents, and what is happening when the chair is being added or pulled away. This provides a repeated visual and tactile aid for understanding the implications of habitat destruction and conservation. By providing concrete examples (dredging, littering etc) and pulling out a chair, the students may build a direct correlation between loosing the game and the destruction of a habitat. A small emotional response is enough to help solidify a lesson. Likewise, when adding back chairs, providing concrete examples of what students can do, helps reinforce these key concepts. The critical discussion at the end of the activity centers around the people on the edge of the classroom – those students who were not in the circle in the middle. These students represent the people of the island who “rely on the fish for food.” The discussion here is aimed at helping students understand that as a community in the Marshall Islands, we rely upon the fish for our own survival and well being. If fish habitats are destroyed and fish cannot survive there, then our own communities will face severe challenges as well. Engaging students in this discussion will help to solidify the second and third objectives of the lesson pertaining to the importance of habitat conservation. 8 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Lesson Outline: Overview: Objectives: By the end of the lesson plan the students will be able to: - Explain and give examples of habitat - Tell the importance of coral and the marine habitat - Recall the value of marine habitats to Marshallese society - Give example of how to conserve and protect habitats Vocabulary: - Habitat - Coral Reef - Habitat Destruction - Herbivore Fish - Dredging Materials: - Students’ chairs for activity - Trash from classroom trash can for activity - Visual aids if available for coral and coral reef Preparation: - Push student desks to the side of the room and place a ring of 6-10 chairs in the middle, with other chairs facing towards the circle (preferably with students not in the room yet) - Write vocabulary words on the board - Gather several items of “clean” trash from the classroom waste basket for use in part two of the game Introduction: Preparation: arrange chairs in a circle and move desks and tables to the outside for a musical chairs game. Upon entering: have students take a seat in a chair, including those in the middle of the room. Introduce the topic of the lesson: marine habitat conservation “What is a habitat? “ Students may not have answers for this question. Proceed. 9 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Activity 1: Musical Habitats Resources required: Chairs from classroom Volunteers for each chair in the middle Summary: The students sitting on the chairs in the circle represent fish, their chairs represent the habitats, and those students on the sidelines represent the people on the islands. With each round of musical chairs, one chair is removed, and the instructor explains a certain form of habitat destruction that “caused” the habitat loss. Students are questioned for their understanding throughout. Introduction: Explain to students that those students sitting in the chairs are now fish, living in the coral reefs around the island Explain to students that their chairs are now their habitats: the place they live. Ask students what kind of habitat a fish might live in? Explain to students that the students around the edge are the Marshallese living on the islands, who rely on the fish for food. Explain that “right now” there are enough fish for the people on the island to eat, but that if we destroy the habitat things might change. Explain that when you start counting, each “fish” will stand up and “swim” around the chairs. When you count down from 10-0, each “fish” will try to find a habitat. However, with each round, you will show another kind of habitat destruction, and one of the habitats will be taken away 10 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Start: Have students stand up. Explain one of the following forms of marine habitat destruction while you gradually remove one chair from the circle. Alternatively, ask students for an example of something that would hurt a coral reef o Littering and getting trash in the coral reef o Spilling oil off a boat into the water o People stepping on the delicate coral o Dredging o Big-net fishing Count down from 10 as students circle the chairs. When you reach 0, they will rush to find seats, and one will be left out Use this to explain what has happened: because of (whatever form of habitat destruction was chosen) a habitat was destroyed, and now, this fish cannot survive here. Repeat With each round, ask students - What destroyed the habitat? Answer: Whatever you stated at the start of the round when you removed the chair - What happened to the fish? Answer: They couldn’t survive Wrap Up: When only 1 “fish” is left, ask students if they think that the people (the students on the edge) could survive off just this one fish? This is the realization that destroying habitats destroys the ability to eat fish. Have students find a seat (keep the chairs arranged that way) Objectives Review: Outline the objectives for the students: Ask students what a habitat is and what an example might be (might not have answer) Write on chalkboard “What a habitat is” Ask students why it is important to conserve habitats? Write on chalkboard “Importance of marine habitats” Ask students what they can do (might not have answer) Write on chalkboard “How to conserve habitats” 11 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Presentation: Introduction to Habitats: Explain the meaning of habitat Explain the things a habitat gives an animal: food & shelter Give examples of habitats Review remaining vocabulary: - Coral Reef: a collection of corals in shallow, generally tropical waters, home to many species of fish and other marine animals - Habitat Destruction: the act of damaging a habitat to the point that animals can no longer survive there - Herbivore Fish: certain species of fish that survive by eating only plants such as algae and plankton. They take care of the habitats so everything stays in balance. Surgeonfish and parrotfish are two familiar MAR examples, often seen browsing and scraping on reef algae. - Dredging: the act of digging out coral and rock from the ocean to deepen channels or build new land spaces on the island. Discuss the importance of habitats: - Tell the important of the coral and marine habitat and give example why fish always near the coral (show the students the Marshall Island Marine and terrestrial Habitats.) - Explain how animals that we rely on live in these habitats - Without the habitats, these animals are gone, and we cannot survive - Give the model of a lot of people living in a village and then houses slowly being destroyed, until everyone lives in one, over-crowded house: cannot survive well Discuss habitat destruction: - What kinds of activities are destructive of habitats? o Dredging, stepping on coral, bad fishing practices, etc o Give an example of destructive fishing practices: over fishing, long-net fishing, Tank spear fishing etc. o Activities that disrupt the balance: killing too many herbivore fish means algae will take over: Discuss how to conserve habitats as kids: - Cleaning up trash from water, and not throwing trash on the ground or water - Making sure oil from boats doesn’t go in the water - Not stepping on coral o Give example of Blu crew ocean beach and ocean clean up, example of marine habitat, example of habitat destruction Remind about how value the Marine conservation to the Marshallese societies and protected areas. 12 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Group Review: The teacher will ask student the following questions: - Why do so many fish live in a coral reef? - What will happen as there are fewer and fewer habitats left? Activity 2: Reverse Musical Habitats Resources required: Chairs from classroom Volunteers for each chair in the middle Trash from trash can Summary: The one remaining chair in the middle is now the only habitat. The student in the chair is the only fish. At the start of each round, the instructor will explain a form of habitat conservation, and add in a chair and a “fish” to the game. When the counting finishes, every fish will have a habitat. This will be repeated several times, each with different kinds of habitat conservation. Introduction: Ask students what the student sitting in the chair is They are a fish. Ask students what the chair represents? It’s a coral in the reef: a habitat Ask students who those sitting on the edge are? They are Marshallese on the islands who rely on the fish for food. Ask students if they could survive on the one fish there? No they couldn’t Start: Have students stand up. Explain one of the following forms of marine habitat conservation while you gradually add one chair into the circle and pull one more student into the game. Alternatively, ask students for an example of something that would help to conserve a coral reef - Picking up trash/not littering - Not stepping on coral - Preventing oil spills Count down from 10 as students circle the chairs. 13 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 When you reach 0, they will rush to find seats, and everyone will find a seat Use this to explain what happened: because of (whatever form of habitat conservation was chosen) there are more habitats and more fish Repeat With each round (2-3 rounds) ask students - What helped to conserve the habitat? Answer: whatever you stated at the start of the round when you added the chair - What happened to the habitat? Answer: It could recover, and come back - What happened to the fish? Answer: They came back Wrap Up: When all three new chairs have been added, ask the students if they think the people (the students on the edge) could survive now that there are a lot more fish left? This is the realization that conserving marine habitats helps people survive too. Have students find a seat (keep the chairs arranged that way) Independent review: Ask students the following questions. Have students raise their hand to answer or call on certain kids. - What is habitat? - What is an example of how to protect marine habitats? o Pick up trash/don’t litter o Don’t step on coral o Prevent oil from going into the water - What is it important for us to protect marine habitat? 14 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 Program Customization: The lessons of the Environmental Education Initiative are developed expressly for the Marshall Islands, and meant to be well-fit to students’ lives and levels of understanding. However, these lessons were also designed on Majuro, and built to fit the local context of that community. While they can certainly be presented in their current form anywhere in the Marshall Islands, a quick review of the materials can enable you to ensure that these materials are directly applicable to your own students. This brief document describes a process for customizing these materials to your classroom. This is simply a suggestion for customization, and you should take whatever measures you see fit for tailoring these lessons to your students. Process: Customizing the lessons involves 5 basic steps: A. Reviewing models B. Reviewing vocabulary C. Checking activities and resources D. Checking current understanding E. Incorporation and recording Before any customization, it is important to recognize the structure of these lessons to understand where customization may occur. These lessons are built upon a lesson-design model which includes seven individual parts: Anticipation: The first part of each lesson is meant to catch students’ attention and switch their thinking from the last topic to the new topic. It is often an activity or semi-disruptive action to introduce the topic. This may need to be modified depending on individual context. Objectives: Next, the actual objectives of the lessons are introduced to students in a very direct manner. These objectives are the cornerstone of the lessons, and will likely not need to be directly modified unless you feel it necessary. Concept introduction: This is where the individual objectives are discussed at length, any vocabulary is introduced, and the actual content of the lesson introduced. It is effectively the “lecture” of each lesson. This part will require some attention to detail in its customization to ensure it is fully applicable. Modeling: Visual, locally-relevant, concrete examples or analogies are presented to give students a full grasp of the topic they are being introduced to. This will need to be tailored to each unique community context. Verification: Questions are asked of the class about what they have just been learning to verify that some level of learning has occurred, and that students understand the lesson. This will likely not be modified very much as it is based on the central objectives. Activity: Typically an opportunity to get kids out of their seats, this part of the lesson puts kids’ new knowledge to work. Activities are built on the principle that young children learn best when 15 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 they are moving and active. Some customization will naturally take place to fit these activities to the space available to you, but should otherwise require little change. Final review: After the activity, students are asked to review the central themes of the lesson overall, and the lesson concludes. This will not require much, if any, custom effort. Reviewing Models: Throughout the lesson, examples, models, and imagery are used to help describe the focus of the lesson to students. In particular, this imagery and modeling takes place in sections 3 and 4. It is suggested that you take note of each example or model that is presented for students’ understanding. Check to make sure that these examples are fitting to the context of your own students’ lives. Are they something that students would relate to directly? In analyzing these examples, it is useful to ask 3 key questions for each example: 1. Is this example/model/image something that is present on this island? 2. Is this something that my students see/experience on a regular basis? 3. Who in my class might not know what this example is? If anyone in your class might not be familiar with a certain example or if there is any suggestion that the example might not be something students would find in their daily lives and be familiar with, then a new model ought to replace it. In finding a fitting replacement, consider what the example was attempting to demonstrate. What was the concept behind it? What idea or principle did it demonstrate? With the purpose in mind, a new example ought to fit three criteria: 1. Must be present on the island you are working on. 2. Must be something that students in your class would encounter regularly and be very familiar with. 3. Must not exclude any member of your class: even if most students are familiar with a topic, if one student has no idea what that example is, this will prevent further learning. Reviewing Vocabulary As a part of each lesson, a series of new vocabulary words are introduced. Like the models and examples, the way these vocabulary words are introduced may be the difference between successful learning, and bewilderment. Students should have a solid grasp of all vocabulary by the end of the lesson, so it is crucial to ground their introduction in their existing vocabulary knowledge and contextual understandings. In analyzing the vocabulary words, introduced during section 3, consider the following: 1. Is this vocabulary word something students already know? If so, it can be easily incorporated and reviewed, but not focused on. 16 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 2. If it is new, does the definition rely on concepts that the students already know? If so, then it can be introduced with confidence and no extensive modifications. 3. If not, does this vocabulary word require additional understanding for my students to grasp? This may impact the format of the lesson, depending on the word. If the vocabulary is either already familiar to students, or introduced in a manner that builds on what you know your students to be familiar with, then no real modification is necessary. If, however, the word would not be familiar to students, and its explanation would be complicated to describe, some additional modification may be required. To modify complicated vocabulary here are a few suggestions: 1. Review the entirety of the lesson. Note where that particular vocabulary word comes into play. 2. Consider the role of that vocabulary in the lesson. In a lesson on habitats, the word “habitat” is absolutely critical to carrying out the lesson. However, the term “ecosystem services” may be essential, but also able to be explained using other, simpler terms that don’t first require an understanding of the term “ecosystem” 3. Determine a definition that builds upon students’ existing vocabulary. 4. Consider how you might define the term using examples, local imagery or other relevant principles. Follow the guide to modifying examples to ensure that sufficiently applicable examples are used. Checking Activities and Resources: Each lesson centers on an activity or activities. These activities are meant to be able to be performed in any classroom setting using only those materials that would already be present in the classroom. However, because the lessons were designed in Majuro, some island contexts may not have been considered, and it is important to take stock of the actual materials required for each activity before introducing the lesson. To review the material requirements, read over the lesson section of each lesson. Consider how you would conduct these activities in your own classroom. If the lesson suggests students use their chairs for something, consider if every student will have a chair that will be fitting for the use suggested. If it requires using classroom trash, check to see if there is actually a classroom trash bin that is regularly full enough to use. Should you lack any of the resources required for the successful conduct of the lesson, consider the following: 1. How is that material or resource used in the lesson? Ex. Chairs used as imagery for habitats and place-holders for student participants in a “musical chairs” game 2. Is it possible to conduct the lesson or activity without that particular resource? Ex. Could you play a game of “musical chairs” without chairs? 3. What could be used in place of the required resource? Ex. If there aren’t enough chairs, could something else represent habitats and be a placeholder? Perhaps simple pieces of paper on the floor. 4. Where might I be able to acquire that resource prior to the lesson? Ex. Perhaps additional chairs could be brought in from another classroom or another facility. 17 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015 5. How could the activity or lesson be modified to not require that resource? Ex. Could you do another activity or change the activity sufficiently to not involve that resource at all? If a lesson’s activity cannot be conducted without key resources, and alternatives are not available, please contact the distributor of these materials to request assistance in modifying the lesson. Checking Current Understanding Critical to performing these lessons is ensuring that they build upon existing student knowledge and understanding. To ensure that this lesson builds upon existing knowledge, and is not too high or low level for your students, a simple survey can be performed based on the learning objective of the lesson. 1. Review the learning objectives for the lesson. 2. Turn each learning objective into a question for the students (good examples can be found in section 7 of each lesson) 3. Have your students write a short answer to each of the 3-4 questions for your review. The results of this simple survey will help you to understand whether your students are able to comprehend the lesson you are planning to introduce, or if the lesson is too basic. Consider: a. Should the vast majority of students answer the questions with completely irrelevant or wrong answers, then the lesson may be a bit advanced, and a serious review of the vocabulary and examples should be conducted before presenting the materials. In this case, it is worth considering if the lesson ought to be given to more advanced students, or those of a higher grade. b. Should part of the class answer with vaguely correct answers, but most not answer correctly, then the lesson may require some modification to be applicable and at level. Particularly, review the vocabulary to make sure it is necessary and well-defined. Also review the concept introduction in section 3 to make sure it is not going over students’ abilities. c. Should part of the class answer correctly and some with error, then moderate modification should be made to ensure it is at level, and the lesson should be presented. d. Should most of the class answer correctly, and only some answer incorrectly, then it is possible that less modification would be necessary, or that more advanced material and discussion may be possible. Review the concept introduction in section 3 to see that it builds on the demonstrated knowledge in the surveys, not repeating it. e. Should the vast majority of students answer the questions correctly and with nuance, then the lesson may be below their level. Consider if it would be possible to present it to lower-grade students, or if there are means of advancing the lesson to a higher level. Incorporation and Recording Once all modifications to the lesson have been made, it is requested that you make note of the changes you have made and send a copy of these changes to the distributor with your comments. This will enable this lesson to be better presented to students throughout the Marshall Islands. 18 Living Islands 501c(3) and MICS - 2015