Guidelines for Text Complexity Analysis

advertisement

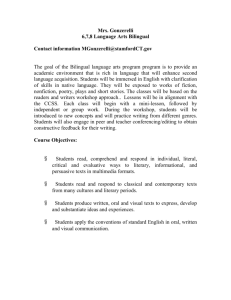

Guidelines for Text Complexity Analysis When planning instruction for the Common Core State Standards, it is important to select texts that provide students with the opportunities to meet the complexity expectations of the Common Core State Standards outlined in each grade by Reading Standard 10. Text Complexity Analysis Process: 1. First, determine the quantitative measure to place a text in a grade-level band. Quantitative tools measure dimensions of text complexity – such as word frequency, sentence length, and text cohesion – that can be analyzed by a computer and are difficult for a human reader to evaluate. Use one of the quantitative tools in the Short Guide to Quantitative Tools to obtain a quantitative measure for the text. These tools produce a score that correlates to a grade band: 2. Then, using your professional judgment, perform a qualitative analysis of text complexity to situate a text within a specific grade band. Qualitative tools measure such features of text complexity as text structure, language clarity and conventions, knowledge demands, and levels of meaning and purpose that cannot be measured by computers and must be evaluated by educators. (1) Structure. Texts of low complexity tend to have simple, well-marked, and conventional structures, whereas texts of high complexity tend to have complex, implicit, and (in literary texts) unconventional structures. Simple literary texts tend to relate events in chronological order, while complex literary texts make more frequent use of flashbacks, flash-forwards, multiple points of view and other manipulations of time and sequence. Simple informational texts are likely not to deviate from the conventions of common genres and subgenres, while complex informational texts might if they are conforming to the norms and conventions of a specific discipline or if they contain a variety of structures (as an academic textbook or history book might). Graphics tend to be simple and either unnecessary or merely supplementary to the meaning of texts of low complexity, whereas texts of high complexity tend to have similarly complex graphics that provide an independent source of information and are essential to understanding a text. (Note that many books for the youngest students rely heavily on graphics to convey meaning and are an exception to the above generalization.) (2) Language Conventionality and Clarity. Texts that rely on literal, clear, contemporary, and conversational language tend to be easier to read than texts that rely on figurative, ironic, ambiguous, purposefully misleading, archaic, or otherwise unfamiliar language (such as general academic and domain-specific vocabulary). (3) Knowledge Demands. Texts that make few assumptions about the extent of readers’ life experiences and the depth of their cultural/literary and content/discipline knowledge are generally less complex than are texts that make many assumptions in one or more of those areas. (4) Levels of Meaning (literary texts) or Purpose (informational texts). Literary texts with a single level of meaning tend to be easier to read than literary texts with multiple levels of meaning (such as satires, in which the author’s literal message is intentionally at odds with his or her underlying message). Similarly, informational texts with an explicitly stated purpose are generally easier to comprehend than informational texts with an implicit, hidden, or obscure purpose. 3. Lastly, educators should evaluate the text in light of the students they plan to teach and the task they will assign. Consider possible struggles students might face, as well as brainstorm potential scaffolding to support students in unpacking the most complex features of the text. Reader and Task Considerations enable the educator to “bring” the text into a realistic setting—their classroom. You can use the Questions for Reader and Task Considerations to aid this process. NOTE: In most cases, the qualitative analysis of the text will align with the quantitative measures assigned to a text. However, there are some exceptions. Narrative fiction in grades 612 is not always reliably quantifiable. For example, while To Kill a Mockingbird has a Lexile that places it in the 4-5 grade band, the complexity of the layers of meaning in this text can push it up to the 9-10 grade band for instruction. Similarly, poetry and drama are often not reliably quantifiable. Sometimes preference should be given to the qualitative measures for these texts. This type of exception, however, should rarely be exercised with other kinds of texts as it is critical that students have adequate practice with texts that fall within the quantitative band for their grade level. Some texts for kindergarten and grade one contain features to aid early readers in learning to read that are difficult to assess using the quantitative tools alone. Educators must employ their professional judgment in the consideration of these texts for early readers.