Mid-Term Exam Senior IB Visual Arts 2013 Henson

advertisement

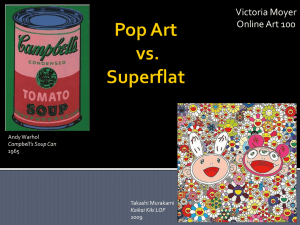

Mid-Term Exam Senior IB Visual Arts 2013 Henson-Dacey Create three integrated pages, include images (with citation), also include personal connection along with analysis. Page 1: Street Art Street artist RONE recently completed work on this great five-story mural on building facade at Nollendorfplatz in Berlin. The artist is known for straddling the line between beauty and decay by creating large-scale depictions of idealized portraits that appear perfectly composed at a distance, but a closer inspection reveals signs of deterioration and imperfection. You can see more photos of this piece over on photographer Henrik here. All photos courtesy Henrik http://r-o-n-e.com/artwork/ n. Famous for his sumptuous paintings of glamorous women, in particular an often recurring image of his socalled Jane Doe, Rone’s work attempts to locate the friction point between beauty and decay, the lavish and despoiled, creating an iconic form of urban art with a strongly emotional bent. Producing many of his early works either through a process of stenciling or screen-printing however, like fellow Everfresh member Meggs, Rone’s movement toward a more freehand style of practice has enabled a certain amount of openness and looseness to seep into his images, a rawness which can perhaps be seen to have enhanced the affective quality they contained. A key individual in the Melbourne street art scene then, Rone’s images have not only appeared all over his adopted city itself but have increasingly began to appear all around the world too, his trademark figures, his heroic, alluring, cinematic icons manifesting themselves in ever larger, more elaborate and emotive forms. Rone’s work swiftly become an unmistakable part of the Melburnian cityscape, his images suffusing the landscape at an almost unimaginable rate. Using their “calming beauty”, their innate contrast to the walls that they grace, they thus fuse its dirt with decorativeness to form an ephemeral elegance, a transient beauty amidst the chaos of the street. Page 2: Warhol & Basquiat (an artistic collaboration) Andy Warhol and Jean Michel Basquiat, Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper), 1985-1986, Acrylic and oil stick on punching bags, 42 x 14 x 14 in. (106.7 x 35.6 x 35.6 cm.) , The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh © AWF “It was like some crazy-art world marriage and they were the odd couple. The relationship was symbiotic. Jean-Michel thought he needed Andy’s fame, and Andy thought he needed Jean-Michel’s new blood. Jean Michel gave Andy a rebellious image again.” Ronny Cutrone quoted in Warhol: The Biography by Victor Bockris, Da Capo Press: Cambridge, 20030, pp. 461-2. In the early 1980s, Andy Warhol and painter Jean-Michel Basquiat began a series of collaborative paintings. Like Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat constructed a persona that he presented to the public that was contradictory to who he truly was.During press interviews, Andy Warhol also gave contradictory statements about his past. Emerging first out of the Grafitti Art movement, Basquiat choose SAMO as his “tag” referring to “Same Ol’.” Weaving the story of himself as a Caribbeanborn ghetto kid who lived in a box on the streets of New York, Basquiat was, in fact, the educated son of a middle class African-American lawyer from the borough of Queens. Warhol liked the confrontational Basquiat who was continually running against the grain of both the law and the art world. Basquiat has been credited with inspiring Warhol to return to painting on canvas like he did during the early 1960’s.1 The two artists collaborated on numerous paintings together. Warhol usually painted fi rst, allowing Basquiat to layer over his work. On many occasions Basquiat wrote a word, and then drew a line through it, simultaneously stating and contradicting the word’s meaning and associations. In 1986 Warhol was deeply involved in a large series of paintings derived from The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci. The series was commissioned by the art dealer Alexandre Iolas, who offered Warhol a show in Milan right across the street Detail, Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper), 1985-1986, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh © AWF Andy Warhol and Jean Michel Basquiat, Collaboration (Dollar Sign, Don’t Tread on Me), 1984-1985 acrylic, silkscreen ink, and oil stick on canvas, 20 x 16 in. (50.8 x 40.6 cm.) The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh © AWF from the real Last Supper. Warhol worked on the project on and off for a year, and the source material of da Vinci’s Christ image became the central motif of Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper), a collaborative sculpture with Basquiat. A number of other key factors contributed to the execution of this sculptural installation: Warhol had been following a rigorous exercise regimen, which included boxing with his trainer; Basquiat, his young collaborator, was an avid fan of professional boxing (Basquiat once painted a punching bag with a mocking portrait of his dealer); both artists were unsteady at that moment from the barbs of negative artworld criticism. The text, “judge,” and other symbols were Basquiat’s contributions. Warhol admitted that he tried to paint some images like Jean-Michel, and said that the “paintings we’re doing together are better when you can’t tell who did which parts.”2 He also questioned the aesthetics of their collaborations saying, “[Jean-Michel] painted over a painting that I did, and I don’t know if it got better or not.”But Warhol gave credit where it was due: “Jean-Michel got me into painting differently, and that’s a good thing.” 3 Guiding questions for integrated page: 1. What does symbiotic mean? 2. When you look at Ten Punching Bags can you discern which artist painted the various elements? 3. What are the general differences between Warhol’s work and Basquiat’s work? 4. Do you think that Warhol and Basquiat were equal partners in their collaborative paintings? Why or why not? Page 3: Art and Philosophy Bernard-Henri Lévy, France’s most famous public intellectual, becomes a curator with a heady new exhibition about the eternal struggle for truth. Slide Show It is very likely that if you sit with Bernard-Henri Lévy over green tea in the lobby of the Carlyle hotel and he explains his wildly ambitious new exhibition at the Fondation Maeght in the South of France, you will not entirely understand the concept. You will worry that you are being airheaded for not following all the Kant and Goethe thrown around, but you will nonetheless be entirely persuaded that the exhibit is fascinating and important, because Lévy is nothing if not a truly great talker, a creator of excitement, a seducer of more cautious or less resourceful minds, even in his English, or maybe especially in his English, which he apologizes for with panache. The exhibit, “Les Aventures de la Vérité,” which will open on June 29, is so grand and sweeping and baroquely complex in its ambitions that it would take an extremely long book to explain what it is trying to do, and in fact the French polemicist has written a 400-page tome, which is actually the catalog. The images below is part of the curated exhibition (use these as a form of comparison). Lévy is trying to document a lively struggle between art and philosophy to illuminate human experience, in which the two are sometimes rivals and sometimes allies. He says, “The exhibit will tell the story of how the idea of truth takes shape, disappears and reappears through the two mediums of art and philosophy, and how the two struggle for control of what truth is.” One of the exhibit’s most intriguing premises is that art has very little to do with its place and time. The show will mingle old and new, contemporary and classical, a crucifixion and a Crisis X , Lévy is interested in the tension between them, the ways they will interrogate each other, the truths they will tease out from the confrontation. As he explains, “I am mixing time periods so as to make order. I want a Basquiat and a Bronzino to speak to each other.” We are so used to walking into a gallery organized by a single painter or a period or theme that this exhibit is meant to challenge or defy more comfortable kinds of museum going. Torn out of their usual more predictable contexts, the artworks require us to see them differently, posing provocative questions. Lévy tells me that he himself does not collect art, which seems surprising for someone of his vast resources and cultural interests. He says this is because his father, who was very political, did not believe in art collecting. He believed art was for everyone, and collections were elitist, an idea that somehow communicated itself to his son. So this is Lévy’s first collection, and it is not strictly his. “It will go through my hands like sand,” he says. We are familiar, of course, with philosopher kings, but is there a new breed of philosopher curators? Another popular philosopher, Alain de Botton, has also turned his attention to art and is curating his own philosophy-infused exhibits that also mix time periods, which will open next year in Amsterdam, Melbourne and Toronto. “The truth is that many visits to museums can be intellectually rather lacking, and philosophy can help us find new ways to give art space in our lives,” he says. “Art can tell us truths philosophy can’t, but it may require a philosopher to tease out these truths.” One could easily imagine artists bristling at this noisy intrusion of philosophers into their creative space. But Marina Abramovic told me about the gloomy rainy day when Lévy, with what she called his “film-star quality,” walked into her studio in SoHo. “I had never seen him before, and I thought, Oh my God, he really has his shirt open,” she says. “But he came into my studio and said so precisely in very few words what it was about. He was very clear. Philosophers can tell you about your work, and aspects of it you don’t know. They can see things much faster than artists because artists work from the subconscious, from a place beyond words. Philosophers kind of give order to art.” He tells me, for example, about visiting Jeff Koons in his studio. He has brought with him Kant’s “Critique of Judgment” so that Koons could read a passage from it about the sublime. The first thing Koons says to him is that he can’t read it. He is against judgment. Lévy says, “But the passage is not about judgment, it is about the sublime.” Koons refuses to read from the book. In the end they pick another text, from Aristotle. Koons paces around his studio while reading it and everyone is happy. Later this month, Lévy’s vision will come to life when the exhibit opens its doors. One wonders after the Champagne is drunk, and the chic museum goers vanish into the warm summer night, and the guards go home to their families, and the lights are dimmed in the vast empty rooms, what will happen when the Basquiat begins to speak to the Bronzino, when they begin bickering over who is boring or who is crazy or whether that is blood on the Basquiat, or whether the New York subway or a chapel in Florence is a more sacred space, or what Christ suffered for, and Warhol’s “Studies of Jackie” begins to murmur in dulcet tones to “The Veil of Saint Veronica”? It would be the great culmination of Lévy’s dream to be the fly on that wall. Citation: New York Times, Culture Section, by Katie Roiphe, May 31, 2013 Bernard Henri-Levy Jean –Michel Basquiat Crisis X 1982 Bronzino Crucifixion 1540