Paschen-May 1 The longer one thinks of Hip Hop and attempts to

advertisement

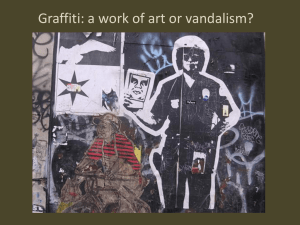

Paschen-May 1 The longer one thinks of Hip Hop and attempts to relate it to contemporary art, the relationship between the two appears incredibly overlapped and tightly engaged as today’s artists prod and explore the reality of modern culture. Brooklyn-born Jean-Michel Basquiat was the mastermind and creative genius behind making such an association possible. Basquiat left home at age 17 to live the streets of New York at the same time Hip Hop was emerging from the catacombs. Under the pseudonym SAMO (meaning “Same Old Shit”), Basquiat and childhood friend Al Diaz collectively wrote cryptic messages on the outside of gallery walls and public structures in and around the lower east side and SoHo area 1. Deemed as graffiti by some, Basquiat’s work was recognized by gallery owners and members of the art world as something unique and incredibly remarkable. Instead of “tagging” public structures for territory purposes, Basquiat’s form of graffiti stood out because of its poetic and mysterious qualities. Often commenting on social problems and visually translating them through enigmas of his imagination, Basquiat’s block-lettered, street style is seen repeatedly in work throughout his short, yet profound art career.2 By 1981, the artist was plucked from the streets and placed in the basement of Annina Nosei’s gallery in New York’s Chelsea District where she exposed his work to the limelight of society. He later joined Mary Boone in 1982 and by this time, his art career was rapidly gaining momentum. Michael Wines, writer for The New York Times comments: By the time he was 24, Mr. Basquiat’s paintings were selling for $10,000 to $25,000 to the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art and to such collectors as S. I. Newhouse, Richard Gere and Paul Simon. In two years, Mr. Basquiat had completed the rocket trip from graffiti artist to celebrated NeoExpressionist.3 Smith, Roberta. “Collisions on Canvases That Still Make Noise” The New York Times. pg. 1 Hoffman, Fred. “The Defining Years; Notes on Five Key Works” in Basquiat edited by Marc Meyer. pg. 129 3 Wines, Michael, “Jean-Michel Basquiat: Hazards of Sudden Success and Fame,” The New York Times. pg. 3 1 2 Paschen-May 2 Basquiat had successfully made the transition from intellectual, yet struggling street kid to overnight superstar status whose paintings demanded high prices and the immediate attention of the world. The artist was living high and fast and showed it through his lofty spending and frequent drug use. He would often give the money earned from his paintings to strangers on the street and it was not uncommon for Basquiat to paint in expensive Armani suits.4 This precocious artist did not place his priority on being just another flashy avant-garde artist of the moment. He did not focus his energy into being a pretentious art snob, even though his hyped career would suggest so. Basquiat was the master of combining image and text in such a way that forced the viewer to look under the raw, simple figures to find the social and personal commentary. In works such as Untitled (Skull) 1981, and Per Capita 1981, Basquiat throws the concepts of personal identity and mortality into the forefront of the viewer’s thoughts. Through these paintings and countless others, Basquiat springs a new branch of direction for contemporary art and reshapes its future forever. The painting Untitled (Skull) 1981 is to this day, one of Basquiat’s most famous paintings and subsequently so, it remains one of the most expensive. The painting is of a giant head, filling the pictorial field with an assortment of earthy tones, complimented by areas of blue. The head floats in the middle of orange and blue tones whose brush strokes are severely painterly and crude. The lines of the painting seem doodled and primitively placed but are also meticulous and intricately repetitive. The lines clearly define the shape of the head and distinguish the facial features of the figure. The forms and shapes are very geometric, adding to the crude and basic quality the painting expresses. The lack of any vanishing point gives the work a flat, primitive look5, yet the distinguishing lines reveal how 4 5 Wines, Michael, “Jean-Michel Basquiat: Hazards of Sudden Success and Fame,” The New York Times. pg.3 The raw, childish ‘doodle’ style, lacks sophisticated hyper-realistic forms Paschen-May 3 truly realistic the figure is. The viewer is immediately drawn to the bright displays of vibrant color that is juxtaposed by areas of black and white. As the viewer’s eyes move around the image, they encounter the disassembled scribble style within the face and are forced to jump around, deciding which ones define which facial features. Line and color are the main factors Basquiat uses to make this happen. The repetitive lines seem to mimic that of a hip hop beat, moving the viewer through the work, along the contours of the figure. Franklin Sirmans, co-curator of Brooklyn Museum’s 2005 Basquiat exhibition explains, Basquiat was much like a turntablist, spinning narratives in the paintings. We can truly read Basquiat as a deejay in his approach to making art.6 The work as a whole forces the viewer to see the inner workings of both Basquiat’s thought process and physical technique as the semi-sporadic, yet organized lines zip around on the picture plane. Although the work may appear to be haphazard and disorganized, the formal qualities of the work reveal it to be both aesthetically and methodically intuitive. At first glance, the viewer of Basquiat’s Untitled (Skull) is confronted with an image that appears grotesque and contains a significant representation of death. On closer inspection however, the very opposite becomes evident. The head appears alive and alert to the world around it because the lines and layers within the image create an incredible amount of tension and kinetic energy. Richard Cork of The Times in London comments on the work: At the age of 20 he [Basquiat] produced a large canvas called Untitled (Skull) which shows how gifted Basquiat really was. It also reveals the turbulence of his imagination, dominated by mortality at an age when most of us relegate death to some reassuringly vague future 7 6 7 Sirmans, Franklin. “In the Cipher Basquiat and Hip Hop Culture” in Basquiat. Edited by Marc Mayer. pg. 91 Cork, Richard. “The Lost Poet of New York” The Times. pg. 1 Paschen-May 4 Possessing qualities suited with death such as the bone structure of a raw, human skull, exposed teeth and black color allows the painting to instantly represent Basquiat’s perspective on mortality. Considering the painting was created at such a young age, it proves Basquiat was completely aware of, and in touch with the realities of the human experience. The artist lacked the naivety regarding death common in young, civilized society and it is seen within this painting. Subsequently, Basquiat’s adherence to mortality in Untitled (Skull) represents a type of identity for the artist--not in terms of race, specifically--but as a human being. The painting helps exemplify Basquiat’s spiritual connection with the world and with himself as an intuitive and intellectual person who is quite in touch with the reality of life and death. The second work which exemplifies Basquiat’s connection with the concepts of identity and mortality is Per Capita, 1981. The picture plane consists of a vague cityscape structure and a black figure in Everlast boxer shorts, holding a torch. Surrounding these figures is a mixture of layered paint, the phrases “Per Capita” and “E Pluribus..” and a partial list of the United States in alphabetical order.8 The lines in this painting force the viewer’s eye to move rapidly around the canvas while they struggle to discern what is going on. The lines form basic, geometric shapes which are then overlapped with several layers of very painterly brushstrokes. The layers of paint force the viewer to search for the meaning beneath them. Like several of Basquiat’s paintings, Per Capita contains abrupt shocks of complimenting colors. The yellow and blue within the barely distinguishable cityscape draws the viewer’s attention and allows them to recognize it as such. The canvas plain is flat because the figure of a black man is strictly two-dimensional with its feet in profile view. 8 Hoffman, Fred. “The Defining Years: Notes on Five Key Works” in Basquiat edited by Marc Meyer. pg. 134 Paschen-May 5 There is also no indication of a vanishing point and therefore, there is no linear perspective. Instead, Basquiat layers paint and repeatedly covers what he initially painted with thick white and gray strokes. Richard Marshall, curator of Basquiat’s first Whitney Museum of American Art in 1992, comments on the artist’s work: What gives Basquiat’s works their special appeal is the fact that the words and symbols that he uses function almost like a code, serving to conceal various themes such as political, social or racial problems. Each has its own meaning, and when viewed as a whole it is immediately apparent that he has intentionally arranged various symbols on a field. Although the meaning is not readily surrendered. Visually, his works appear very powerful with wild tones and striking images, but I also suspect a deep sense of poetic sensitivity.9 Marshall’s views are easily applicable to Basquiat’s Per Capita 1981 because the painting is loaded with symbols. The list of States and their citizen’s per capita incomes, the crude black figure and the phrases “E Pluribus..” and “Per Capita” together represent monetary inequality within the United States.10 Not only is Basquiat commenting on the gap between the wealthy and impoverished in this painting, but he is also depicting where he as a young, black artist from the streets of New York stands within this dichotomy. Richard Schur, professor of interdisciplinary Studies at Drury University explains Basquiat’s use of the black figure in his work: Basquiat does not attempt to create dignified portrait of black humanity or an explicit demand for equality or social recognition. Rather, the image appears to reinforce white supremacist stereotypes of black inferiority because the image itself depicts African-American culture in crude terms.11 9 Kawachi, Taka. King For A Decade; Jean-Michel Basquiat. pg. 73 Hoffman, Fred. “The Defining Years: Notes on Five Key Works” in Basquiat edited by Marc Meyer.pg. 134 11 Schur, Richard. “Post-Soul Aesthetics in Contemporary African American Art” African American Review. pg. 644 10 Paschen-May 6 He purposefully does not idealize the black figure in the painting yet still establishes a sense of iconic quality within it by dressing it in a boxer’s shorts. The figure also stands holding a torch which represents hope or could also be a tool to literally shine a light on the social problems presented in the painting. Basquiat creates a representation of his identity as a member of the capitalist economy, establishes his preconceived role in such an environment as a young black man and conveys his identity as an artist by visually representing these aspects in such a unique way. Basquiat makes it apparent that although he is very young, he is very in touch and aware of what is around him and he is capable of visually communicating it like no one else before him. Despite his unfortunately short life and art career, Jean-Michel Basquiat shook the art scene for the rest of time. He created a new form of collage that reflected his graffiti experience and included layered images, repeated text and splashes of color. Christopher Knight of the Los Angeles Times explains Basquiat’s unique style: The meticulous analyses in Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks and the layered, Xray-like renderings of the human body in Gray’s Anatomy are also obvious incentives; you find references to both throughout Basquiat’s work.12 While alive, Basquiat joked that he could actually draw. The fact that he chose to keep the figures of his work basic, raw and childish speaks volumes for what he valued most. Basquiat found a way to display collage in a new way. Roberta Smith, art writer for The New York Times relates Basquiat’s racial identity to his style: More than many of his white counterparts, Basquiat had a pressing subject to explore in this hybrid word-image style: being black in America. As a middleclass black of Caribbean descent growing up in urban America, he was himself a hybrid who approached his race from a number of angles. [Smith continues] And Knight, Christopher. “Hail the king; Jean-Michel Basquiat’s use of Drawing and Color…” The Los Angeles Times. pg.2 12 Paschen-May 7 throughout [Basquiat’s work], a recurring theme is the volatile mix, in white America, of blackness, talent fame and death.13 Smith articulates the artist’s focus on his personal identity and rational relationship with mortality through his artwork. The mixture of text and image reflects his personal mixture of race and how this affects his relationship with the world around him. As seen in all of his work, Basquiat is successful at creating his own style of painting and imagery that captures the viewer’s attention and forces them to both see and search for the underlying meanings and social/personal commentary. 13 Smith, Roberta. “Basquiat: Man For His Decade” The New York Times. pg. 2 Paschen-May Notes 1. Smith, Roberta. “Collisions on Canvas that Still Make Noise.” The New York Times, March 11, 2005, Section E, Late edition. 2. Hoffman, Fred. “The Defining Years; Notes on Five Key Works” in Basquiat. Marc Mayer. Merrell Publishers Limited. Exh. Cat. London, England: Brooklyn Museum, 2005. pg. 129 3. Wines, Michael. “Jean-Michel Basquiat: Hazards of Sudden Success and Fame.” The New York Times, August 27, 1988, Section 1, Late City Final edition. 4. Wines, Michael. “Jean-Michel Basquiat: Hazards of Sudden Success and Fame.” The New York Times, August 27, 1988, Section 1, Late City Final edition. 6. Sirmans, Frank. “In the Cipher Basquiat and Hip Hop Culture” in Basquiat. Marc Mayer. Merrell Publishers limited. Exh. Cat. London, England: Brooklyn Museum, 2005. pg. 91 7. Cork, Richard. “The Lost Poet of New York” The Times, March 12, 1996, Features Section, pg. 1 8. Hoffman, Fred. “The Defining Years; Notes on Five Key Works” in Basquiat. Marc Mayer. Merrell Publishers Limited. Exh. Cat. London, England: Brooklyn Museum, 2005. pg. 134 9. Kawachi, Taka. King For A Decade; Jean-Michel Basquiat. (Kyoto: Korinsha Press, 1997) pg. 73 10. Hoffman, Fred. “The Defining Years; Notes on Five Key Works” in Basquiat. Marc Mayer. Merrell Publishers Limited. Exh. Cat. London, England: Brooklyn Museum, 2005. pg. 134 11. Schur, Richard. “Post-Soul Aesthetics in Contemporary African American Art” African American Review, 2007, Volume 41, Number 4. pg. 644 8 Paschen-May 12. Knight, Christopher. “Hail the King; Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Use of Drawing and Color Jolted the Art World” The Los Angeles Times. July 19, 2005, Home Edition. pg.2 Works Cited Cork, Richard. “The Lost Poet of New York” The Times, March 12, 1996, Features Section. Hoffman, Fred. “The Defining Years; Notes on Five Key Works” in Basquiat. Marc Mayer. Merrell Publishers Limited. Exh. Cat. London, England: Brooklyn Museum, 2005. Kawachi, Taka. King For A Decade; Jean-Michel Basquiat. (Kyoto: Korinsha Press, 1997) pg. 73 Knight, Christopher. “Hail the King; Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Use of Drawing and Color Jolted the Art World” The Los Angeles Times. July 19, 2005, Home Edition. Schur, Richard. “Post-Soul Aesthetics in Contemporary African American Art” African American Review, 2007, Volume 41, Number 4. pg. 644 Sirmans, Frank. “In the Cipher Basquiat and Hip Hop Culture” in Basquiat. Marc Mayer. Merrell Publishers limited. Exh. Cat. London, England: Brooklyn Museum, 2005. pg. 91 Smith, Roberta. “Collisions on Canvas that Still Make Noise.” The New York Times, March 11, 2005, Section E, Late edition. Wines, Michael. “Jean-Michel Basquiat: Hazards of Sudden Success and Fame.” The New York Times, August 27, 1988, Section 1, Late City Final edition. 9 Paschen-May Untitled (Skull) 1981 10 Paschen-May Per Capita 1981 11