Indications for operative vaginal delivery

advertisement

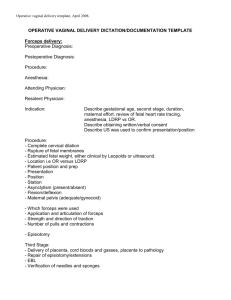

Simulation Training Assessment Tool (STAT)– Vacuum Assisted Delivery Indications for operative vaginal delivery The most recent ACOG Practice Bulletin on this subject (June 2000) states that “No indication for operative vaginal delivery is absolute.” This being said, in the right hands, these procedures can allow you to deliver a fetus safely and rapidly and they are an essential part of any obstetrician’s training. Indications for an Operative Vaginal Delivery according to ACOG include: - Presumed or imminent fetal compromise (example – severe variable decelerations or repetitive late decelerations with pushing) Maternal indication for shortened/passive 2nd stage (example – severe maternal cardiac disease or CNS disease) Prolonged 2nd stage of labor (see below for definitions as they differ for nulliparous/multiparous pts) Aftercoming head of a vaginal breech delivery Having stated the common indications for an operative delivery, there are other criteria which must be met prior to performing an operative delivery. You must know the following: - Size of baby (EFW) Leading part of fetal skull: at +2 station or lower Adequate pelvis Adequate pain control Cervix is completely dilated Known fetal head position (i.e. OA, OP, LOA, etc) Ruptured membranes Acronym: SLAACKR Size of baby – The first parameter you must consider is whether or not you believe this infant is small enough to be delivered vaginally. This is why performing Leopold maneuvers at the time of admission is important in establishing an estimated fetal weight. If you feel that the child is large (fetal weight > 4000gms) then, although you may attempt the delivery if you feel the pelvis is adequate (or large enough to allow passage of the fetus), there is a higher chance of a shoulder dystocia and you must be prepared for this complication. Leading part of fetal skull at +2 station or lower – If the fetus is not at least at +2 station, then you are performing a mid forceps delivery, which is only rarely used when it is felt that the fetus can be more rapidly delivered by this method than be cesarean. Adequate pelvis – If, on clinical pelvimetry, you determine that the patient has a contracted pelvis, then performing an operative delivery is contraindicated. Regardless of how much traction you apply, if the space is too small, the baby still won’t fit. Adequate pain control – In general, some form of conduction anesthesia (spinal/epidural) is required to perform a forceps delivery. The pressure from the application can be very painful. With a vacuum device, less anesthesia is needed for the application, which is one reason this device is often used. If the patient does not have conduction anesthesia, then a pudendal nerve block may be attempted. Cervix completely dilated – Unless the cervix is completely dilated, an operative vaginal delivery should generally not be attempted. If any part of the cervix is caught in the forceps or vacuum device then significant cervical lacerations and hemorrhage can occur. Known fetal head position – In order to appropriately apply either forceps or a vacuum device, it is imperative that you know the baby’s head’s position. This can be very difficult after a patient has been pushing for several hours and developed caput, which is why is it important that you check the fetal head position on EACH labor check and document it in the record. Ruptured membranes—membranes must be ruptured if a vacuum delivery is to be attemped. Vacuum Delivery (Basics) Use of the vacuum device, although used by midwives and family practice physicians, can result in complications just like forceps. After determining that an operative vaginal delivery is indicated, and going through your acronym SLACCKR, consider whether you can use a vacuum. (i.e. gestational age at least 34 wks, no known bleeding disorders, and no need for rotation) General reasons for choosing a vacuum device over forceps are, experience with vacuum device and less need for pain control for placement. Application and Traction: After counseling the patient and confirming fetal head position, empty the patient’s bladder. Then place the vacuum device such that it covers in the midline the vertex. Make sure that it does not overlap either the anterior or posterior fontanelles, and that there is no vaginal tissue trapped in between the vacuum and the fetal scalp. When the patient experiences a contraction, have your assistant bring the pressure up to an appropriate level, which should not generally exceed 500-600mmHg or 0.6 to 0.8 kg/cm2 (This is where you have to read the directions on the individual devices). After you have done this, apply traction with each push in the appropriate axis (see the forceps portion for this description.) It is important to avoid a “rocking” motion and gentle, steady traction should be used. Between pushes RELEASE the pressure on the vacuum! This will decrease the incidence of cephalohematoma as much as possible. If the vacuum comes off three times, it is generally wise to abandon the procedure. Also, when this happens, recheck the fetal head position, because, when the fetus is in the OP position, this will often occur. Contraindications for Operative Vaginal Delivery: General Contraindications: Specific for Vacuum: - Bone demineralization condition (Osteogenesis imperfecta) - Bleeding disorders (hemophilia, von Willebrand’s, etc) Fetal head is not engaged Head position is not known. - Preterm status (< 34 wks gestation) (because of risk of fetal IVH) - Face presentation Complications of Operative Vaginal Delivery There are potential complications involved in the use of both forceps and vacuum devices. It is imperative that you are knowledgeable regarding both maternal and fetal complications so that you can do your best to avoid them, and how to correct them should they occur. Vacuum* – Maternal Complications: - Vaginal lacerations: These tend to occur less often than with forceps, although if any vaginal tissue is caught between the vacuum device and the fetal head, these can cause significant hemorrhage afterwards. Any operative delivery, especially those that involve an episiotomy, can result in third/fourth degree lacerations, although vacuum deliveries are less likely than forceps to cause this. Cervical lacerations Postpartum hemorrhage Endometritis (This occurs in 8% of vacuum deliveries. (Williams, 1991)) Fetal Complications: - Scalp lacerations (especially if a twisting movement, or “cookie-cutter” motion is used to attempt to rotate the infant.) - Cephalohematoma (approx 15%) (Johanson 1999) - Subgaleal hematoma (bleeding between cranial periostium and epicranial aponeurosis) - Retinal hemorrhages - Neonatal jaundice *The overall incidence of serious complications with a vacuum extraction is approximately 5%. (Robertson 1999) Long-term Infant Consequences: There have been two long-term studies of the cognitive development of children delivered by forceps or vacuum extractor and these found no difference when compared to infants delivered spontaneously. (Wesley BD 1993, Ngan HY 1990). The forceps study included nearly 1200 children delivered via forceps and the vacuum study nearly 300 vacuum deliveries. Another study reported that the risk on intracranial hemorrhage was not increased in over 7000 operative vaginal deliveries (both vacuum and forceps) when compared with spontaneous vaginal delivery. (Garnella, 2001) These facts are important to know when counseling patients as they are often nervous when you discuss these interventions with them. References: Gailbraith RS. Incidence of neonatal sixth nerve palsy in relation to mode of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1994; 170:1158-1159. Gardella C, Taylor M, Benedetti T, Hitti J, Critchlow C. The effect of sequential use of vacuum and forceps for assisted vaginal delivery on neonatal and maternal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol Oct 2001; 185(4):896-902. Johanson RB, Menon BKV. Vacuum extraction versus forceps for assisted vaginal delivery (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 1999. Oxford: Update Software. Operative vaginal delivery. American College of OB/GYN Technical Bulletin #17, June 2000. Ngan HY, Miu P, Ko L, Ma HK. Long-term neurological sequelae following vacuum extractor delivery. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1990; 30:111-114.