Trafficking of mesenchymal stem cells

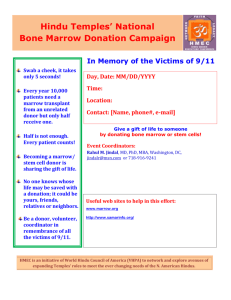

advertisement