3. Sustainable Surfboards

advertisement

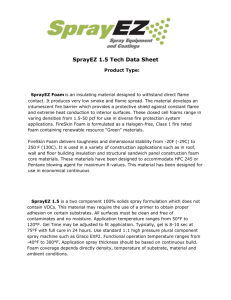

Sustainable Surfboards By Sean Sullivan We are nothing without nature and our craft. Abstract This study is an assessment of the current situation surrounding the creation, production and marketing of an environmentally friendly alternative to the modern polyurethane foam, fibreglass, and resin surfboard. The surfboard has evolved from the 100% recyclable, sustainable wooden board used by the Hawaiians into a toxic composite of polluting materials used by surfers around the globe. This study attempts to define the environmental impacts of the construction and usage of the common polyurethane foam, fibreglass and resin surfboard as the justification of the need for a sustainable alternative. Taj flying at J-Bay on his firewire. In order to assess the current situation regarding the creation, production and marketing of an environmentally friendly surfboard, surfers were surveyed and interviews were conducted with surfboard shapers and others involved in the surf industry. Those surveyed and interviewed were questioned on awareness of environmental issues, assessment of the market for an environmentally friendly alternative to the modern surfboard, and barriers and incentives to the creation, production and marketing of a sustainable surfboard. Crude but clean - a blast from the past – one of the original recyclable wooden boards used by the Hawaiians The conclusions of the research indicate that there is only a generalized idea of the environmental effects of surfboard construction and although some surfers expressed an interest in a sustainable surfboard, this interest is not being articulated to the surf industry. As a result, despite some pockets of pro-active individuals and companies involved in the production of more eco-friendly alternative surfboards and materials, the surf industry as a whole is not currently involved in creating or producing a sustainable surfboard. Instead, the surfing community seems contented to accept the status quo. This report recommends a campaign that would promote awareness of the associated environmental impacts of surfboard construction as the necessary first step towards sustainability. What is needed to create an environmentally friendly alternative to the common surfboard is a collaborative effort involving surfers, shapers, foundation organizers and the surf industry as a whole to work together to address this issue. As a tribe surely we should aspire to create some sustainable craft for our groms Introduction 1.1 Statement of Problem Surfing has the image of a very pure sport; it is an interaction with simple forces of nature on a sustainable level, leaving no trace on the natural environment. However, although a surfer may leave no trace on the face of a crashing wave, the environmental impacts of surfboard construction are leaving a lasting impression on the natural environment. The largely unspoken truth is that the construction of the modern surfboard involves the use of harmful petrochemicals and processes that result in dangerous by-products harmful to both the surfboard builder and the environment. An examination of the history and evolution of the surfboard will show that what was once an entirely sustainable surfboard has become a polluting composite. 1.2 Surfing Roots in Indigenous Hawaiian Culture The history of surfing begins in the South Pacific. The first recorded description of surfboard riding is taken from the journal of Captain Cook in which he describes the native Hawaiians surfing in a late 1770’s entry, “Twenty or thirty of the natives, taking each a long narrow board, rounded at the ends, set out together from the shore. The first wave they meet they plunge under… (and) rise again beyond it…” “As soon as they have gained, by these repeated efforts, the smooth water beyond the surf they lay themselves at length on their boards and prepare for their return… their first object is to place themselves on the summit of the largest surge, by which they are driven along with amazing rapidity toward the shore.” (Cook, in Young 1994, p. 31) The Hawaiians and Tahitians were recorded surfing by Westerners as early as the late 18th century, but a brief examination of the ritual nature of surfing and surfboard making within Hawaiian culture proves that surfing had been part of Hawaiian culture for a long time before Captain Cook’s journal entry. 1.3 Surfboard Construction by Indigenous Hawaiians Initially, the surfboard was made from all natural materials. Surfboards were made from three types of wood: ula (breadfruit), koa (Hawaiian mahogany), and wili wili (Hawaiian balsa). According to Nat Young’s “History of Surfing,” the Hawaiian ritual began by choosing a tree and placing a red fish (Kumu) at the foot of its trunk. Then “the tree was cut down and the fish placed with a prayer in the hole dug at the root. After this ceremony the surfer chipped away at the tree with a stone adze until it was reduced to the size of the board he wanted: 14 to 16 feet long for the alii, 10 to 12 feet long for the commoners.” (Young 1994, p. 31) The board was then brought to the beach and essentially sanded smooth using a combination of specific types of granulated coral and rough stone. Finally, the board was given a glossy black finish by rubbing the root of the Ti plant or pounded bark along its surfaces. (Young 1994, p. 31) 1.4 From Hawaii to Australia: The Evolution of the Modern Surfboard In this sense, the original surfboards were totally organic, and despite extremely minimal tree felling and fishing, virtually impact free. The original surfboards of Hawaii were 100% recyclable. As surfboard shapes and designs have changed over the past 200+ years, the surfboard has gone from the 100% recyclable heavy Hawaiian wooden boards to a lightweight foam/ fibreglass/ resin composite that is unable to be recycled. Although boards are now much lighter and tuned to allow surfers enhanced mobility on the face of the wave, they break more easily and are unable to be recycled. This begs the question, how did we get so far from the Hawaiian model, and have surfboards really been evolving, or is it a case of devolution? What led the surf industry to pursue this environmentally destructive model? When did this path begin in Australia? Clearly, the surfboard that introduced Australia to surfing was a finless wooden surfboard, specifically a piece of sugar pine. However, surfboard construction would change many times before the modern foam/ fibreglass/ resin surfboard became a mainstay. Note how many changes relate to issues of weight, waterproofing, and durability. See the timeline below: 1.5 How a Modern Surfboard is Constructed In simple terms, the modern surfboard is created as follows from three main ingredients: foam, fibreglass and resin. A shaper begins with a blank, or piece of foam that was formed to a basic oval shape by the blank manufacturer. The blank contains a stringer, which is a piece of wood glued in between the two longitudinal halves of the blank, down the centre. The shaper takes this blank and shapes it to the required shape either by using a planer, or placing the blank into a computer aided cutting machine. The shaping process involves shaping the rails, or edges of the board, the contour of the bottom of the board, and the shape of the tail and nose. Once shaped to the desired design, the board is covered in a layer of dry fibreglass cloth on one side, which extends over the edges of the board. The glasser, or person who is charge of fibreglassing the board, pours a layer of resin liquid, which has been mixed with a catalyst (hardener) on top of the board and smooths it out using a small, flat piece of plastic. He repeats this process until the fibreglass is appropriately saturated and adhered to the board, while still wet. Once the resin cures, or hardens, the same glassing process is repeated on the opposite side. Often times multiple layers of glass are applied to each side, requiring curing and sanding between coats. After this is completed, the board is sanded down to smooth out the resin and sometimes polished to give it a glossy finish. Additionally, the builder has to add the fins, a process which involves slotting the fins into the blank itself and fibreglassing the fins on permanently or boring out small holes into the blank which hold plugs with slots for removable fins. A small hole is also drilled into the deck, for a piece of plastic with a metal bar that serves as an attachment point for the leg rope. 1.6 Assessing the Problems of the Modern Surfboard Since the late 1950’s the foam/ glass/ resin board has been the standard for surfers around the world. An examination of the different materials needed to construct a modern surfboard and how these materials are deleterious to both the health of the shaper who creates the board and the environment at large is vital to understanding the need for an environmentally friendly alternative to the modern foam/ glass/ resin surfboard. Just how big is the scope of the problem? Unfortunately, this is unclear. There is no governing body or oversight committee keeping figures on the global surf industry. Although the Surf Industry Manufacturer’s Association does exist, it’s only study in 2004 was a Retail Distribution Study which, for the purposes of this report, established little more than an estimate of annual board sales in the United States (USD$140m). Without reliable figures on the number of surfboards being produced per annum globally it is impossible to estimate the scale of the environmental impacts of surfboard construction. So how can we be sure surfboards are actually hurting the environment? By analysing the environmental and health effects of each surfboard ingredient per se. 1.6.1 Impacts of Modern Surfboard Construction According to the shapers I spoke with, Polyurethane foam (PU) core surfboards account for more than 95% of the boards they create. (Young 2007, pers. comm., 17 April. Dahlberg 2007, pers. comm., 27 April). A look at any surf magazine or out in the water seems to confirm this. The creation of a polyurethane foam blank utilizes processes that are known to give off CO 2, a greenhouse gas, and often employ Hydro-fluorocarbons, which are known to deplete the ozone, as the blowing agent or catalyst. Fibreglass, a fibre made from sand, is safe in the knit form commonly found in surf shops, but is often treated with heavy metals (e.g. Volan is treated with Chromium) and therefore is itself toxic. In surfboard construction, fibreglass is combined with resins to create the laminate, or skin of the surfboard. Polyester resin is used in combination with PU. The polyester resin is combined with styrene monomer, a toxic solvent that thins out the resin into a more workable and liquid form that is able to sanded. Styrene, in addition to being a known carcinogen, is a corrosive substance that is itself a Volatile Organic Compound (VOC). Its fumes are released during its use and it is also a reactive diluent, which means that it becomes part of the cured resin and will continue to emit VOC’s as the resin breaks down. These VOC’s are irritants to nose, skin, eyes, throat, lungs, and can cause central nervous system damage when inhaled in quantity. In the environment, these VOC’s combine with Nitrogen Oxides in the air to create ground level ozone, which is the main component of smog. The excess resin and dirt on a surfboard is cleaned off using acetone, which also emits VOC’s. (Nova Scotia Environment and Labour Dept., 2007.) An inventory of any surfboard shaping room would also probably include commonly used paints, thinners and catalysts like Methyl Ethyl Ketone Peroxide (MEKP), which effect the lungs and central nervous system, in addition to emitting VOC’s. The emission of VOC’s does not stop with construction; as the resins break down they continue to emit VOC’s into the atmosphere. This is particularly bad with PU boards, but even Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) foam in combination with epoxy resins releases VOC’s, albeit much less. According to Fletcher Chouinard, owner of Point Blanks Surfboards, “epoxy resin has 75% fewer VOC's contained in the resin itself and two-thirds fewer VOC's are released into the atmosphere than from polyester resin.” (Chouinard, undated) Note here that although Polyurethane and EPS are recyclable, once they are placed into a composite form (as all surfboards are) it is no longer able to be recycled. It is also important to note that the resins and foam are both petrochemicals. I don’t think it is necessary to get into the associated environmental issues concerning petroleum acquisition and refinement, but it should be noted that the resins needed for surfboards are clear resins, and this means that they require an extensive amount of refining, using large amounts of energy. More of the associated environmental effects of surfboard construction are discussed in the Results section. 1.7 Reasons for the Foam/ Glass/ Resin Surfboard Model Compare all these chemicals that compose the modern surfboard to the wooden surfboards rubbed with Ti root and surfed by South Pacific Islanders for many years before the Westernisation of surfing and it is clear to see that surfboards have evolved from a sustainable product into a polluting composite. What was wrong with the old boards? Some would argue that there was nothing wrong with the wooden fin-less surfboards, and the design only changed to accommodate the novices who wanted to learn to surf on something more manageable than a heavy wooden plank. In fact, Tom Wegener of Tom Wegener Surfboards is currently involved in creating boards very similar to the ancient Hawaiian boards. These fin-less Paulownia wood surfboards are similar in shape and plan to the ancient Hawaiian boards, treated only in linseed oil. To Wegener, who is a very accomplished professional long board surfer, the boards represent a challenge and harken back to the times when a surfer needed to be all around waterman – physically fit and a capable swimmer. However, those surfers that desired to cut, stall and turn along the face of the wave demanded increasingly manoeuvrable equipment, and in terms of construction, this mainly met one thing – lightweight. When the foam board replaced the balsa boards, there was a decrease in weight. Since then, surfers have not wanted to look back. Today, competitive pros surfing on the world circuit ride boards with minimal layers of fibreglass on thin foam cores. This minimization of materials adds up to a fragile board when compared to the thicker foam, heavily fibreglassed boards of twenty years ago. Because today’s recreational surfers are keen to emulate these pros and ride the same equipment, the standard short board ridden by the average surfer is extremely lightweight and easily broken. This means the average surfboard is not durable, and has become what equates to a disposable good. There are clearly many environmental and health issues regarding the current surfboard model on offer. But do surfers care? Is there really a market for an environmentally friendly surfboard? 1.8 Current Alternative Technologies The following technologies represent a step in the right direction. They are not an end all solution to the problem of surfboard construction, but an explanation of these technologies is necessary to understanding the current efforts by the surf industry to improve the current model. One such technology is BioFoam. BioFoam is a type of foam that is composed of methylene diphenyl di-isocyanate (MDI) and agricultural oils. This foam is an improvement on current polyurethane technologies because it substitutes petroleum based oils with agricultural based oils and uses MDI instead of the much more harmful (and less expensive) toluene di-isocyanate (TDI). By limiting the use of petrochemicals, and utilizing MDI over TDI, “a preliminary life cycle analysis indicates that using BioFoam results in 36% less global warming emissions, a 61% reduction in non-renewable energy use, and a 23% reduction in total energy demand.” (McMahon, N. Homeblown US, ‘BioFoam’ (brochure). 2007) Another person who has wholeheartedly attempted to look into creating an environmentally friendly surfboard is Chris Hines. Chris is the Sustainability Director at the Eden Project in Cornwall, England and has been developing the Eco Board since summer 2003. (Hines 2007, pers. comm., May 9) The two different Eco Boards use different cores: one uses a balsa, which is a sustainable wood due to its rapid regrowth, the other uses BioFoam. These boards are laminated in a hemp cloth or fibreglass made from recycled glass combined with a plant-based resin. The balsa version is sustainable, and the BioFoam version represents a big improvement over the standard surfboard. Tom Wegener is producing hollow wooden surfboards from Paulownia wood, harvested from tree plantations within Australia. In addition to offering fibreglass covered wooden boards, he also offers a full range of Paulownia surfboards that are only treated with linseed oil. In addition Tom makes "efforts to source the biggest blocks of wood,” (Wegener 2007, pers. comm. 2 May) in order to minimize gluing and waste from off-cuts. Firewire surfboards are another new technology that has only come to the market in April 2006. Firewire surfboards, far from being totally sustainable are an improvement on the standard PU surfboard. Firewire uses an expanded polystyrene (EPS) core with epoxy resins and parabolic balsa rails in lieu of a stringer. Although this represents a very small improvement in environmental impact terms, the EPS/ Epoxy technology is better for the environment, and because the rails are made from balsa, a smaller amount of foam is needed for each board.