The Politics of Yoga: The Neoliberal Yogi and the Question of Yogic

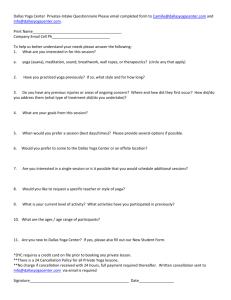

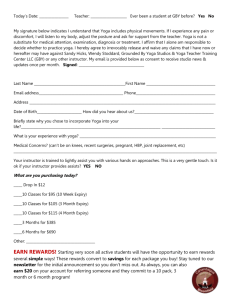

advertisement