Stubager, Rune (2014). The meaning of issue ownership

advertisement

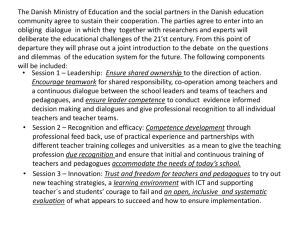

The meaning of issue ownership. Experimenting with measures and meaning Rune Stubager Department of Political Science Aarhus University Bartholins Allé 7 8000 Aarhus C Denmark stubager@ps.au.dk Prepared for presentation in the workshop on Innovative research on public opinion and political behavior at the XVII NOPSA conference, Gothenburg, August 2014. 1 Abstract The concept of issue ownership has attracted increasing attention over the past years. Reflecting the broad appeal of the concept, scholars of both electoral behaviour and party competition have included issue ownership in their analyses producing interesting findings. However, both the definition and measurement of issue ownership – often drawn from Petrocik’s seminal 1996-article – is unclear which constitutes a serious drawback to the further development and understanding of both issue ownership itself and its purported effects. As a step towards a clarification of the meaning of issue ownership the paper reports the results of a Danish survey experiment specifically designed to tap the meaning of issue ownership in the minds of voters. The analyses reveal clear differences, both in raw answers and the influence of voter predispositions, between measures of associative and competence ownership just as a third dimension of emphasis issue ownership is identified. Differences are smaller, yet significant and consistent, between different operationalizations of competence issue ownership. The consequences of for theory and measurement are subsequently discussed. Key words: Issue ownership, political parties, question wording. 2 Recent scholarship has devoted considerable attention to issue ownership as an important aspect of party competition and voting behaviour (Dolezal et al. 2013; Geys 2012; Green-Pedersen and Stubager 2010; Martinsson 2009; Meguid 2005; Meyer and Müller 2013; Narud and Valen 2001). The basic idea is that parties can win elections by promoting issues on which they are perceived by large numbers of voters as ‘best at handling’ problems (see, e.g., Budge and Farlie 1983; GreenPedersen 2007; Petrocik 1996). Among voter-level analysts, this idea has received some backing from analyses showing that voters do indeed tend to vote for parties that they find competent at handling various issues (see, e.g., Bélanger and Meguid 2008; Green and Hobolt 2008; van der Brug 2004; Wright 2012). Issue ownership, in other words, seems to play an important role in determining the balance of power in contemporary democracies. These findings and the increasing scholarly attention to the concept makes it the more perplexing that, as noted by Egan (2013, 51; see also Therriault 2009), the definition of issue ownership is all but clear and consensually shared in the research community. Thus, although most (but certainly not all) of those working with the concept are in agreement about measuring issue ownership by means of survey questions asking respondents which party is ‘best at handling’ given issues there is much less agreement about what issue ownership actually is. Most scholars draw upon the works of Budge and Farlie (1983) and Petrocik (1996) when defining the concept, but the definitions provided herein are far from equivocal and leave open the possibility for different subaspects of the definition – such as parties’ success at solving problems, their policy positions or issue emphasis – to play varying roles. An explicit acknowledgement of this multidimensionality is the distinction by Walgrave and co-authors (Tresh et al. 2013; Walgrave et al. 2012) between two types of issue ownership: competence and associative issue ownership. Whereas the former is captured by the standard measure – i.e., it relates to parties’ competence at handling issues – the latter is defined as ‘the spontaneous identification of parties with issues in the minds of voters’ (Walgrave et al. 2012, 772). As each of these sub-dimensions may be related differently to other variables, including being driven by different factors, the theoretical quagmire characteristic of the field seems to impede a fuller understanding of the causes and consequences of issue ownership. In addition to the absence of general agreement about the definition of the concept, issue ownership research is also challenged by the possibility that ownership perceptions, however defined, are little more than mirror images of other, more well-established, constructs such as party identification or policy attitudes. Thus, research (Bellucci 2006; Kuechler 1991; Stubager and Slothuus 2013) has found that such factors play important roles in determining ownership perceptions. To the extent that the relationships between the perceptions and such factors are strong, it becomes doubtful what and how much is gained both theoretically and analytically by operating 3 with an independent concept of issue ownership: If it is merely a reflection of party identification and/or attitudes, we become little wiser by using a special label. As a step towards answering these challenges it is the purpose of this paper to investigate, by means of a survey experiment, which of a number of sub-dimensions of issue ownership seem to influence answers to the standard ‘which party is best at handling issue X’ item and to what extent answers regarding each of these sub-dimensions are influenced by voters’ predispositions in the form of party identification and policy attitudes. The experiment is carried out on a nationally representative sample of Danish voters and the results across four different issue areas show a consistent pattern with answers to the standard item being more strongly related to respondents’ evaluations of parties qualifications (rather than of their policies) as well as to short (rather than long) term evaluations. Associative issue ownership, furthermore, appears to stand out on its own as does a possible third dimension labelled emphasis issue ownership. In general, ownership evaluations are strongly – yet not completely – influenced by respondents’ predispositions, but the strength of this influence varies across sub-dimensions and issue types (whether valence or positional). In sum, the results make clear that measurement matters to results in ways that have to be taken into account in order for the field to progress. The next section contains a theoretical discussion of issue ownership and its various sub-dimensions. Then follows a presentation of the research design and data employed as well as the analytical strategy. Subsequently the results are presented while the conclusion discusses the implications and presents two ways for issue ownership research to move forward. Issue ownership: One concept, several dimensions As noted, the concept of issue ownership has been, and is currently being, defined in multiple, slightly differing ways by researchers in the field. While offering no direct definition, the seminal work by Budge and Farlie (1983, 287) implicitly defines issue ownership as the perception among voters that for a given issue there is ‘one party that is much more dependable in carrying out the desired objective than others’ where the ‘desired objective’ is the only ‘desirable course of action’ on given issue ‘and the overwhelming majority agree on it’. On this view thus, issue ownership is won by providing voters with desired policy outcomes – something that is not necessarily different from adopting specific policy positions beneficial to large numbers of voters. The positional element plays a much smaller – yet still discernible – role in the most commonly referenced definition of issue ownership proposed by Petrocik (1996, 826, emphasis removed). He sees ownership as deriving from parties’ abilities to ‘handle’ ‘problems facing the country’ where “Handling’ is the ability to resolve a problem of concern to voters. It is a reputation 4 for policy and program interest, produced by a history of attention, initiative, and innovation toward these problems, which leads votes to believe that one of the parties … is more sincere and committed to doing something about them’. Further, he maintains that ‘Ownership of problems is conferred by the record of the incumbent and the constituencies of the parties. The record of the incumbent creates a handling advantage when one party can be blamed for current difficulties. … Party constituency ownership of an issue is much more long-term … because its foundation is (1) the relatively stable, but different social bases, that distinguish party constituencies in modern party systems and (2) the link between political conflict and social structure’ (Petrocik 1996, 827). Contained in this definition, thus, is both a performance element, i.e., the parties’ ability to solve problems, the attention devoted a given issue by the parties, and – echoing Budge and Farlie’s definition – parties’ ties with conflicting social groups and, implicitly, the policy positions reflecting such ties. It should be noted, also, that Petrocik points to both short- and long-term aspects of ownership. The multiple dimensions contained in Petrocik’s paper have given rise to some confusion as well as a range of different applications of the issue ownership concept in empirical work. Most explicitly, Walgrave and co-authors have, as mentioned, sought to provide some clarity by dividing Petrocik’s definition in two: Competence and associative issue ownership. The former is defined as concerning ‘whether parties are … the “best” to deal with an issue’ (Walgrave et al. 2012, 772) and is, thus, akin to the performance dimension in Petrocik’s definition. The attention dimension of the definition, however, is what Walgrave and his collaborators define as associative issue ownership – i.e., the spontaneous association between issue and party. Their initial non-experimental tests show the two aspects of ownership to be almost uncorrelated and as having quite varying relationships with other variables (Walgrave et al. 2012); findings that seem to underline the need to pay careful attention to the question of how issue ownership is defined and measured. The attention dimension is also present in the analysis of van der Brug (2004, 215) where issue ownership is measured as voters’ perceptions of the degree to which parties ‘devote special attention to’ a given issue. The very same aspect is featured in Egan’s recent book. On the basis of extensive, aggregate level tests of the relative merits of both the performance, the policy position and the attention dimensions as explanations for the over-time development in issue ownership he defines issue ownership as describing ‘the long-term positive associations between political parties and particular consensus issues in the public’s mind – associations created and reinforced by the parties’ commitments to prioritizing these issues with government spending and lawmaking.’ (Egan 2013, 156). Notice here, the explicit focus on the ‘long-term’ relationships. Likewise, the qualitative study by Wagner and Zeglovits (2014, 287) suggests that survey respondents seem to draw upon the visibility of issues in parties’ campaigns when answering questions about issue ownership. 5 In contrast, Therriault (2009) in an unpublished experimental study comparing different wordings of issue ownership items finds that answers to the standard handling-format are most closely aligned with answers to a format highlighting, in the actual survey item, parties’ reputation for competence in problem solving – termed as being ‘better qualified to handle’ a given issue. In this respect, the competence aspect clearly outperforms a competing framing highlighting parties’ policy positions. Measures focused on such positions, however, also have their proponents in the issue ownership literature. Judging by their choice of survey items, the position dimension seems to be perceived as core to the definition of issue ownership by the researchers behind the Swedish and Norwegian National Election Studies. In both countries, thus, issue ownership is measured by means of questions asking respondents which (if any) party has the ‘best policy’ on a given issue (e.g., Karlsen and Aardal 2011, 139; Oscarsson and Holmberg 2013, 244; see also the discussion in Martinsson 2009, 121-4). The study by Wagner and Zeglovits (2014) indicates that also survey respondents not presented with such direct policy cues in the issue ownership question tend to draw upon the same type of considerations when forming their opinions about issue ownership. This suggests that parties’ policies play an import role to ownership perceptions – precisely as suggested by Budge and Farlie. The argument has, thus, come full circle. While this review is not intended to be exhaustive it does illustrate with sufficient clarity that both the theoretical and empirical approaches to issue ownership tend to vary quite substantially between different specific analyses. While this is somewhat confusing and would seem out of step with ideals of a cumulative research agenda, it might not be more than that. Thus, if the different approaches to definition and measurement end up providing similar results, the consequences might not be that detrimental after all. The results by Walgrave et al. (2012) mentioned above suggest otherwise, however. They find large differences between the competence and associative dimensions of ownership. Likewise, Therriault (2009) also documents differences between the different versions of competence ownership that he examines. On this background it seems likely that similar differences could exist between some of the other approaches discussed above. It is the investigation of this, so far, underexplored question that is the first objective of this paper. Voter predispositions and (the dimensions of) issue ownership The issue ownership literature is challenged not only by the lack of conceptual and analytical clarity discussed above. Looming in the back is also a possible charge of redundancy in the sense that issue ownership perceptions are little more than restatements of voters’ party identification and/or policy preferences – i.e., that issue ownership is always and almost automatically accorded to the party with which a voter identifies and/or with which s/he agrees policy-wise. The policy aspect is, as 6 discussed, explicitly contained in (at least some of) the issue ownership definition(s), but it is, furthermore, not likely that all, or even most, voters conform to the median, issue ownership voter described by Petrocik (1996, 829-30): s/he ‘is uncertain about what represents a serious problem, lacks a clear preference about social and policy issues, is normally disinclined to impose thematic or ideological consistency on issues’. Rather, studies (e.g., Taber and Lodge 2006; Zaller 1992) show voters to be strongly influenced by their predispositions when forming opinions about issues. It seems likely that this may also apply for perceptions of issue ownership. Regarding the possible effect of partisanship, it has, since the seminal presentation of the concept in The American Voter, been acknowledged that ‘Identification with a party raises a perceptual screen through which the individual tends to see what is favourable to his partisan orientation’ (Campbell et al. 1960, 133). Lately, this point has been incorporated in the broader theory of motivated reasoning (see, e.g., Taber and Lodge 2006) where the central point is that both partisanship and other predispositions such as prior attitudes, tend to bias voters’ perceptions of and reactions to various attitudinal objects – such as issue ownerships. Given that parties are highly visible actors in the politics of most democratic countries it seems reasonable to expect most voters to have well-formed perceptions of them. Such perceptions might, subsequently, influence ownership perceptions to such an extent that they crowd out the factors that are thought to form the basis of the latter. The same may apply to policy attitudes. Thus, ownership perceptions may also be driven entirely by whether voters agree with the policies proposed by the parties on a given issue area. Prior research seems to lend at least some credibility to these suspicions. Studies of the individual level roots of ownership perceptions (see, e.g., Bellucci 2006; Kuechler 1991; Stubager and Slothuus 2013) have found considerable effects of both party identification and policy attitudes on such perceptions. Although none of these studies show a complete determination of issue ownership by partisanship and policy attitudes, the effects found are strong enough to warrant specific attention to the question – particularly in light of the conceptual vagueness discussed above. It seems highly likely, that is, that the different sub-dimensions of issue ownership delineated can be influenced to varying degrees by voter predispositions. Most obviously, one would expect policy-based definitions and measures to be most susceptible to such influences, but other dimensions may also be vulnerable in this respect. The crucial thing, however, is that we don’t know at present. It has not been systematically investigated if, and to what extent, different operationalizations of issue ownership are subject to the influences of voters’ predispositions. This is the second objective of this paper. Research design 7 As discussed by Therriault (2009) an ideal analytical set-up for examining whether issue ownership perceptions vary when different aspects of the concept are highlighted to voters would be to ask all respondents in a survey to answer multiple versions of the ownership question for a given issue. However, this set-up is only ideal on the surface. Thus, it is very likely that respondents would feel a pressure to appear consistent across the different version of what they might, not entirely unjustified, perceive as the same question and, hence, give the same answer to the different versions (cf. Schumann and Presser 1996). To avoid this problem, analysts (including Therriault 2009) are now increasingly turning to the use of randomized survey experiments (cf. also Egan 2013, 219). The strength of the experimental method lies in the randomized assignment of the stimuli – the different versions of the issue ownership question in this case. By randomly assigning different question versions to different respondents one can be assured that, except for chance alone, the respondents receiving the different versions are identical and, hence, comparable. This means that the effect of the different versions can be gauged as the difference between the answers given by the different groups of respondents. In the first part of the present analysis, the experimental design will be used to examine the degree of overlap between answers to the standard ‘handle’-version of the ownership question and a range of other versions representing various sub-dimensions of the concept (cf. below). The idea is to use this overlap to determine how much of a role each of the sub-dimensions play in influencing answers to the standard question format, the logic being that the smaller the difference, the more influence a given sub-dimension has on answers to the standard item. The study included seven different versions of issue ownership.1 The first is the standard ‘handle’-version which has featured most prominently in extant research (cf., e.g., Egan 2013, 50) and will function as the key reference in the analyses: 1. Which party is in your opinion best at handling [issue X]? The second and third versions focus on the temporal aspect. Thus, on the one hand, Petrocik (1996, 827) points, as noted, to both short- and long-term factors behind ownership perceptions – ‘the record of the incumbent’ and parties’ constituencies, respectively. Egan (2013, 156), on the other hand, explicitly and exclusively directs attention to the long-term relationships. But how much of a difference does the time frame make? To find out, versions two and three run as follows: 2. If you disregard the current situation and look, instead, at the last 30-40 years which party is then in your opinion best at handling [issue X]? 1 In fact, there were ten versions in total, but three of these are not analyzed here. 8 3. If you disregard the last 30-40 years and look, instead, at the current situation which party is then in your opinion best at handling [issue X]? To assess the influence of the policy dimension implicated in the definitions of both Budge and Farlie (1983) and Petrocik (1996) as well as in the Swedish and Norwegian studies, version four was phrased as: 4. In your opinion, which party has the best policy on [issue X]? In order to test Therriault’s (2009) assertion that it is the competence dimension, i.e., parties problem-solving capabilities, that weigh more heavily in determining answers to the standard item, version five follows his lead in highlighting the parties’ qualifications: 5. Which party do you think is best qualified to handle [issue X]? As can be seen, the first five versions of the experimental stimulus all pertain to what Walgrave and co-authors (2012) defined as competence issue ownership. Given the large differences found between their measure of competence ownership (which, it should be noted, deviates somewhat from the standard format; Walgrave et al. 2012, 774) and associative issue ownership, it seems highly relevant to focus specifically also on this dimension which is assessed by two version in the experiment. The first of these, and the sixth in total, is the measure proposed by Walgrave and collaborators: 6. When you think about [issue X], which party do you spontaneously think about? In both Petrocik’s (1996, 826) and Egan’s (2013, 156) definitions and the empirical application of van der Brug (2004), however, a second aspect of the associative relationship is mentioned: the attention, a party pays to a given issue (cf. also Walgrave et al. 2012, 772). Following a recent study of the strategies parties may employ to affect voters’ issue ownership perceptions (Stubager 2014) this aspect has been operationalized in the following way: 7. In your opinion, which party places the most emphasis on [issue X]? 9 The response categories on all seven versions were all of the nine parties presently eligible to run for parliament in Denmark (the Social Democrats, the Social Liberals, the Conservatives, the Socialist Peoples’ Party, the Liberal Alliance, the Danish People’s Party, the Liberals, the RedGreen Alliance and the Christian Democrats; all except the last were represented in parliament at the time of the study) as well as ‘The parties are equally good/bad at it’ and ‘Don’t know’. In the first round of analyses, all response categories are included whereas the two non-party options as well as the Christian Democrats (which are only selected by very few, if any, respondents) are excluded in the second round of analyses. The issues analyzed The seven different versions of the issue ownership question are asked for four different issues. The choice of these reflects an important discussion in the literature that has not been touched upon above. Some authors (for an explicit example, see Egan 2013, 16-31) restrict the use of issue ownership considerations to so-called valence or consensus issues2 (cf. Stokes 1963; 1992) characterized by agreement over the goals – e.g., most voters prefer low to high unemployment. Such issues are contrasted with so-called position issues where voters disagree over the goals – e.g., how many immigrants to accept into the country. This restrictive approach is also explicitly taken by both Budge and Farlie (1983, 287) and Petrocik (1996, 828). Yet, particularly for Petrocik, the positional element seems to creep back in through the inclusion of parties’ constituencies and their links to social conflict in the definition of issue ownership. Furthermore, the restrictive focus on valence issues is not one that has been upheld in empirical work (see, e.g., Beyer et al. 2014; Karlsen and Aardal 2011; Oscarsson and Holmberg 2013; Stubager and Slothuus 2013; Therriault 2009; van der Brug 2004; Walgrave et al. 2012). It is noteworthy that with the exception of Therriault’s study, all of the analyses just mentioned that include both valence and position issues in the design come from multi-party system whereas Petorcik (1996) analyses the US context and Budge and Farlie (1983) focus on ‘socialist’ vs. ‘bourgeois’ parties, i.e., essentially a two-party logic. In multi-party systems, however, parties located nearby each other on a basic ideological dimension may still be competing. One possible way to succeed in this competition is to appear to be most competent at delivering on a particular position on a position issue. For instance, radical right parties may compete against more centreright parties by being best at handling a tightening of immigration policies. In an issue ownership framework, this would then imply that the radical right party would win votes from the centre-right 2 Egan (2013, 30-1) differentiates between valence and consensus issues. Yet, this distinction appears somewhat unclear and, crucially, matters less for the discussion here. Consequently, I shall not pursue it further. 10 parties if the immigration issue gains prominence on the agenda. At the same time, though, a party representing the exact opposite position on the immigration issue might also stand to benefit from increased attention to the issue if it can succeed in presenting itself as best at delivering opposition to tightening of immigration rules – or perhaps even best at securing a more lenient policy (cf. Geys 2012; Narud and Valen 2001). The issue ownership logic may, in this light, also apply to position issues – at least in multi-party systems. In addition, it should be noted that the distinction between valence and position issues can, at times, appear artificial since it may only take a slight re-framing of a valence issue (e.g., fighting unemployment) to a discussion about how to achieve the goal (e.g., through re-training of the unemployed or by lowering benefits) before the logic changes and positional differences appear. For these reasons, the issues selected for this study are intended to include both positionally and valence-framed ones. The issues are immigration policy, tax policy (both seen as reflecting a positional logic) as well as unemployment and the Danish economy (seen as reflecting a valence logic). Apart from representing the two types of issue discussed, the four selected also have the advantage of being major, important issues that have taken up a large part of the political agenda in Danish politics in recent years. This means that ownership on these issues can be expected to be electorally influential. This feature increases the relevance of the results presented below. Data and analytical methods The data for the study comes from a nationally representative sample of Danish voters collected by the polling agency Epinon in the period September 4 to October 3, 2013. Respondents were drawn from Epinion’s so-called ‘Denmark panel’ which is a standing panel of respondents from which participants for a given survey can be drawn. Respondents are recruited onto the panel from other surveys either online or over the phone with special measures taken to recruit specific hard-to-get groups. The response rate for this specific study was 66 percent and a total of 4,200 respondents took part. These respondents were representative of the general Danish population on age, gender, and region of residence (details available from the author upon request). The experimental set-up consisted of a 37 factorial structure where the first randomization sorted respondents into one of three different version of the associative issue ownership question only two of which are analysed here. The second randomization then sorted respondents into one of seven competence ownership questions only five of which are used here. Each respondent, thus, answered one version of the associative questions and one version of the competence questions – in both cases for all four issues mentioned above. Since assignment at both of the two levels was randomized, there is no dependency between the types of questions answered 11 in the two rounds of the experiment and it is, consequently, unproblematic to compare answers across the seven versions of the ownership question as is done below.3 In the first part of the analyses where focus is upon the degree of overlap between answers to the seven different versions of the question a simple analytical procedure is applied in that t-tests are conducted for the significance of the difference between the proportion pointing to a given party on the standard ‘handling’-question and each of the other six versions. Likewise, the so-called Duncan index is calculated for each of these comparisons. The Duncan index is calculated by summing the absolute deviations between the proportions giving each answer on two different versions of the question and then dividing by two. The score, thereby, reflects how many percentage points would have to re-allocated on one of these two distributions to arrive at the other (see Brandenburg 2005, 320); the lower the score, the more similar are the answers to two versions. A different approach is taken in the second part of the analysis where focus is upon the influence exerted by party identification and policy agreement. Thus, in order to uncover how much of the variation in the answers to the issue ownership questions is accounted for by the two predispositions, I use conditional logit models with the answers to the different versions as the dependent variables and party identification and policy agreement with each party as the independents. Conditional logit models are estimated on a stacked data matrix where each respondent appears as many times as there are alternatives on the dependent variable (i.e., eight in this case where the Christian Democrats and the non-party response options are excluded). This makes it possible to include respondents’ degrees of policy agreement with all parties without risking model breakdown as could result in a multinomial logit model if measures of policy agreement between each respondent and party were included. Policy agreement is assessed by asking respondents ‘To what extent do you agree or disagree with the parties’ policies when it comes to [issue X]? Please use this scale where 0 is ‘Completely disagree’ and 10 is ‘Completely agree’.’ These questions were asked for all parties and all four issues. Party identification was assessed through a series of questions asking, first, if respondents perceive themselves as ‘adherents of a particular party’, second, which one, and, third, if they see themselves as ‘strong’ or ‘not so strong’ adherents. Those not seeing themselves as adherents of a particular party are asked whether they lean towards a particular party. In the analyses, these answers are condensed into one variable taking the value of 0 for parties with which a respondent does not identify/lean, 1 for a party to which a respondent leans, 2 for a party with which a respondent identifies not so strongly, and 3 for a party with which the respondent identifies 3 Due to a built-in supplementary experiment not analyzed here, the probability of assignment to a given version varied somewhat. This explains the differences in the numbers of respondents in the various conditions visible in the tables below. 12 strongly. For most parties, thus, each respondent will score a 0 and a non-zero value will only appear for one party. As focus is not on the specific effects of each of these two variables – but on their combined influence on issue ownership perceptions – I will not present the actual coefficients from the analyses. Rather, I will illustrate their explanatory power by means of McFadden’s pseudo R2 from two sets of models for each combination of question version and issue. The first set of models, the baseline, will include only party constants in order not to force the equivalent of a regression through the origin-assumption on the model. The constants can, furthermore, be seen as reflecting the degree of consensus across respondents, i.e., they pick up the degree of initial agreement. In the present context, thus, these constants will account for larger shares of the variation the more answers are concentrated on one or a few parties. The second set of models adds the party identification and policy agreement measures to gauge how much variation over the baseline these two factors explain for each of the seven versions of the dependent variables. McFadden’s pseudo R2 is defined as R2 = 1 – L1/L0 where L0 is the loglikelihood value of an empty model (i.e., without even the party constants) and L1 is the loglikelihood value of a given model. Hence, the measure, which seems to be the most widely used of the various pseudo R2-measures, can be given a tentative PRE interpretation which is exactly what is relevant in the present case. Results Do differences in issue ownership question-wording matter and what does it tell us about answers to the standard question format? The answers to the seven different versions of the issue ownership question across the four different issues appear in tables 1 and 2. Before delving into the exact numbers, it is instructive to take a more aggregate approach and look at how the parties are ranked on the 28 question version-issue combinations. Thus, if we focus on which parties appear in first, second, and third place, we find a fairly stable pattern that, furthermore, does not surprise observers of Danish politics: On immigration, the Danish People’s Party is the modal category across all seven versions; the Social Democrats appear in second place on five out of seven versions with the Red-Green Alliance occupying the two remaining second places; in third place, the Liberals appear four times, the Social Democrats twice and the Social Liberals once. On taxation, the Liberals occupy all first places and the Social Democrats take six of the seven second places with the Liberal Alliance taking the seventh; in third place, the picture is more mixed with five parties sharing the honour. On unemployment the same three parties occupy all first, second and third places. The Social Democrats take six first places and the Red-Green Alliance the seventh; the Liberals take five second places and the Social Democrats and the Red-Greens one each; the latter take five third 13 places and the Liberals two. Finally, on the Danish economy the pattern is even very stable in that the Liberals take all first places, the Social Democrats all second places while the Social Liberals come in third on all versions. TABLE 1 AND TABLE 2 ABOUT HERE The picture emerging from this initial tallying is one of only minor differences across versions, thus. For most issues the same three parties are in play across all versions and they also tend to fall in the same order on all versions – although with some exceptions particularly in third place (where numbers are often so small that chance variation begins to play a substantial role). Seen this way, the discussion above might seem as much ado about nothing: the voters don’t seem to pay too much attention to the fine print when it comes to issue ownership and a common structure tends to prevail across different versions of the question. In some sense, this might be regarded as good news for the literature since the lack of conceptual clarity doesn’t appear to have any major repercussions for the results obtained. While this conclusion might seem sufficient for researchers mainly interested in the aggregate patterns of issue ownership (e.g., as input in models of party competition) both they and most certainly researchers focused on the individual-level causes and consequences of issue ownership have reason to pause and look at the figures in the tables. On closer inspection, hence, the tables reveal quite large differences in the level of support accorded each party beneath the seemingly similar surface described above – differences that easily pass standard levels of both substantive and statistical significance. The differences are large enough to be of relevance to party analysts since, even though coming out in first place in both instances, it makes a lot of difference to a party whether it is pointed to by more than three out of four or only one out of four – and this is actually the variation registered for the Danish Peoples Party on immigration (compare the Spontaneous AIO and the Long-Term CIO columns in Table 1). Whereas in the former situation it would seem a good bet that the party would stand to benefit from attention to the immigration issue, the outcome might be very different in the latter situation where competing parties might (also) stand to gain (cf. Geys 2012; Narud and Valen 2001). Going further into the tables, it is clear that they contain such a large number of figures and comparisons that they cannot all be meaningfully discussed; hence, focus has to be on patterns arising across issues. At this level, it can, first, be noted that the questions seem to work equally well for both valence and positionally framed issues. There are no discernible patterns in the use of the non-party categories across the two issue types and answers also appear equally consistent with 14 the parties’ behaviour for both issue types. There is not in this material, therefore, any basis for restricting the use of the issue ownership concept to only one issue type. A second notable, general point is that answers seem to be fairly spread out across parties as well as the two non-party response categories – particularly on the five competence ownership versions where no party attains the support of more than 1/3 of respondents. On the associative versions, and the spontaneous one in particular, a higher degree of concentration can be noted. Even for these versions, it is only on immigration, however, that a single party (the Danish People’s Party) can be seen as the issue owner in the sense that it dominates completely. The use of the two non-party categories also deserves notice. These are used fairly widely, totalling between 7.2 and 34.9 percent of responses which, for some issue-version combinations, makes them contenders for first choice. The two categories, but ‘Don’t know’ in particular, are used least in the spontaneous associative version. This result should not be too surprising since this version asks for respondents’ immediate reactions rather than a carefully thought-through and weighted answer. The high prevalence of non-party answers in some versions underlines the need to include such categories on ownership measures and tells the substantive story that up to 1/3 of voters may be rather confused about issue ownerships. Turning then to the core question of the differences in the substantive answers between the different formats, the tables lend very strong support to the non-experimental finding of Walgrave and co-authors (2012) that perceptions of competence and associative issue ownership vary substantially. Thus, judging from both the Duncan index scores and the significance tests,4 the two associative versions consistently (although with a partial exception for the emphasis version on the Danish economy) deviate more from the standard handle-version than any of the (other) competence versions. Further, there seems to be no consistent differences between the two associative versions in this respect: they are equally different from the handle-version. In relation to the theoretical discussion, this finding seems to raise some doubts about Egan’s (2013, 156) focus on commitment-driven associations as the core of answers to the standard ownership questions (and, indeed, of the concept itself). On most of the issues analysed, there simply seems to be very substantial differences between answers to the two types of question versions. Looking at the relationship between the two associative versions, the table also reveals quite large differences. Thus, judging by the Duncan index scores the differences between these two versions are larger than the differences between each of them and the standard handle-version on all issues except immigration. Substantively, this implies that the spontaneous association between a 4 In the following discussion, I shall mainly refer to the Duncan index scores, but all patterns (or lack thereof) picked up by the index are mirrored by the results of the t-tests although the latter tend to be less sensitive to differences because of the limited number of respondents for many party-issue combinations. 15 given party and an issue does not seem to be driven, to any large extent, by perceptions that the party places a lot of emphasis on the issue as was surmised by Walgrave and collaborators (2012, 772). In fact, the results would seem to support the conclusion that the emphasis version taps into a third dimension of issue ownership, different from both the competence and associative dimensions. Following the phrasing of the question, this third dimension could be labelled ‘emphasis issue ownership’. Obviously, more research is needed to establish the causes and consequences of this dimension. Narrowing focus to the five versions of competence issue ownership, a number of highly interesting observations can also be made. Thus, across the four issues two clear patterns emerge. First, the short-term version is consistently, and on the valence issues substantially, more closely related to the standard version than is the long-term version. In other words, answers to the standard version are driven more by short- than long-term considerations. This is not to imply that the latter have no relevance, but the result seems to question another aspect of Egan’s (2013, 156) definition: that issue ownership is a long-term phenomenon. By the results obtained here, it seems more shortterm. This also means that the standard question may have a hard time incorporating the long-term dimension entailed in Petrocik’s (1996, 827) definition as discussed above. In turn, this might explain why Stubager and Slothuus (2013; see also Stubager 2014) have found a relatively weak relationship between voter perceptions of parties’ links with specific constituency groups (e.g., the well-off and the lowest income groups) and ownership perceptions even though this features as an important part of Petrocik’s definition. Second, answers to the best qualified-version are consistently, and again more strongly on valence than position issues, closer to answers to the standard version than are answers to the best policy-version. This finding, which mirrors Therriault’s (2009) results, would probably be considered good news by many issue ownership researchers since it implies that the competence dimension which plays a large role not least in Petrocik’s widely cited definition has a stronger influence on answers to the standard question than the slightly competing policy position dimension. This is particularly so since the latter dimension seems to entail a higher risk of redundancy as compared to policy preferences – a worry that, as we shall see below, is not without reason. For researchers basing their issue ownership analyses on the best policy-version, the results may give cause for some consideration about what it really is their measures are tapping into. In sum, this first round of the analyses has shown that it does seem to matter to responses – in some cases even quite a lot – how questions about issue ownership are phrased. Apart from the methodological point entailed in this observation, it has the substantive implication that the multiple dimensions found in issue ownership definitions can, to no small extent, also be identified empirically. The present study has, thus, uncovered a potential third dimension, emphasis issue 16 ownership, to supplement the two already identified competence and associative dimensions. Furthermore, the experiment showed that answers to the standard handle-version are driven more by short- than long-term considerations and more by evaluations of parties’ qualifications than their policies. The next round of the analysis will examine the degree to which the various versions also differ with respect to the influence on responses exerted by voter predispositions. Is issue ownership a redundant concept and does any redundancy vary across question versions? As noted, the influence of party identification and policy agreement on answers to the seven versions of the issue ownership question across the four issues is gauged by means of McFadden’s R2 from conditional logit models with the latter as dependent and the two former, as well as a set of party constants, as independent variables. The results appear in Table 3. The table shows that the different versions of the issue ownership question also vary when it comes to the effects of voter predispositions. First, it can be noted that the explanatory power of the party constants varies considerably – from a low of 6.6 to a high of 61.3, and that even for the same issue (immigration). The influence of this initial consensus among respondents is consistently weakest for the best policy-version and strongest for the long-term version (except on immigration). Particularly the former should not surprise too much since the best policy version, on the face of it, would seem most open to partisan driven influences (as discussed below, this is indeed the case). A second, preliminary point to note is that there is much less variation in the total level of explained variance, particularly within the two sets of competence and associative versions. Among the former, the figures range in the 60s whereas they are substantially lower (except on immigration) among the latter. TABLE 3 ABOUT HERE Turning then to the core question of the influence of the predispositions, it is clear, from the bottom row for each issue in the table, that these matter more for the competence than the associative versions. On the two associative versions, thus, the added explanatory value of the two independent variables can be less than two percentage points (as applies for the rest of the differences, even this minor one is significant, however). This is particularly the case for the spontaneous version and on the two positionally framed issues whereas the contribution on the emphasis version and the two valence issues are up to 30 percentage points. These differences may reflect that the spontaneous version invites the least strategic reasoning on behalf of respondents, or put differently, that it does not include any manifestly positive words or phrases (such as ‘best’ something) that can cue partisan motivations in the answers. On valence issues, however, such reasoning may sneak back in as the policy goals are so positively valued that the mere association between issue and party 17 becomes desirable to a motivated reasoning mind. Across the seven versions, these figures show that while none of the versions are completely redundant, some of them are well on the way. Interesting patterns can also be identified among the five competence versions. Consistently, the long-term version is least influenced by the predispositions (the differences between the two models hover around 30 percentage points) while, on average, the best policy version is most influenced (with differences around 50 percentage points). Concerning the latter, the results would seem to reflect the strong element of normative judgement entailed in asking which party has the best policy on a given issue, a format that comes close to asking which party is best liked – at least it comes closest among the seven versions in the analysis. Concerning the former, the findings indicate that answers to this version have a fairly high degree of independence from the predispositions; it is, in other words, the competence version, among those analysed, that appears the least redundant. Answers to the standard version are placed in between the long-term and best policy versions when it comes to the influence of voter predispositions – although, it should be noted, much closer to the latter than the former. This implies that partisanship and policy agreement account for about or just below half of the variation on the standard version. By most standards, a large proportion – perhaps even worryingly large. Seen from the perspective of minimizing overlap between issue ownership measures and measures of other concepts, thus, the associative versions and the long-term version appear preferable. In sum, the analyses reveal a considerable amount of predisposition influence across the seven versions of the issue ownership question; more so for competence than associative versions, but more on valence than position issues among the associative versions. The specific patterns across the versions fit well with the patterns uncovered in the first part of the analysis. First, and most clearly, the large differences between the competence and associative dimensions re-appear, just as the difference between the associative and emphasis dimensions also shows up, thereby further underlining the distinctness of the three dimensions and, by implication, the necessity to pay attention to all three. Among the competence versions, the difference between the standard and long-term versions becomes even clearer with the long-term version appearing in a league of its own with a high level of initial consensus and a low level of predisposition influence. In contrast, and as found above, the short-term version looks much more like the standard version. Likewise, across the issues the results for the best qualified version also resemble those for the standard version more than those for the best policy version – again an echo of results from the first round. Conclusion The analyses have focused on two related questions: 1) To what extent do answers to issue ownership questions vary with different question versions and what does this tell us about answers 18 to the standard question version? and 2) To what extent are issue ownership perceptions influenced (maybe even made redundant) by voter predispositions and (how) does this vary across different question formats? The short answer to both questions is ‘quite a lot’. Both parts of the analysis have shown substantial differences in answers as well as predisposition influence hereon across the seven versions of the issue ownership question included in the experiment. The discussion above has shown how these differences have implications for some of the more commonly applied definitions of issue ownership. On this background, the obvious question to address is what this implies for future research. How, if at all, can the findings presented here be of use in improving our understanding of issue ownership, its causes and effects in future work? I see two possible ways to follow. The first would be to adjust the definition of the concept to reflect the findings above about what aspects drive answers to the standard measure – and care less about overlap with voter predispositions. This would imply a definition of issue ownership as ‘a short-term perception of parties’ qualifications at handling certain issues’. This is, of course, not an entirely novel definition in that it draws upon aspects that are contained in existing definitions, but at the same time it deliberately excludes other aspects that are also contained in existing definitions – notably the long-term perspective, policy and emphasis related aspects as well as spontaneous associations. The second approach entails the adjustment of measures to encompass core aspects of the definition and to minimize redundancy vis-à-vis other concepts and measures. This would imply a conscious application of separate measures of all of the three ownership dimensions so far identified – competence, associative, and emphasis. The two latter can be captured by the two last versions included in the experimental setting applied here. According to the results, however, the unique content of the competence dimension is perhaps best captured by the long-term version, perhaps adjusted to include the competence cue of the best qualified version. The measure would, thus, run as follows: ‘If you disregard the current situation and look, instead, at the last 30-40 years which party is then in your opinion best qualified to handle [issue X]?’ This measure has the advantages of being relatively independent of predispositions, it focuses explicitly on the competence aspect, and it is likely to be stable over the short run. It should provide, therefore, for a more stable, focused and independent assessment of the competence dimension while the two other measures can then tap the related, but (as documented) distinct associative and emphasis dimensions. The choice between the two approaches seems to rest on whether the historically unclear and likely atheoretically driven (cf. Egan 2013, 50) choice of the standard question format should continue to determine the direction of issue ownership research. Or whether the recent increase in our knowledge about the content, causes, and consequences of issue ownership should be taken into account when trying to move the field forward. 19 In making the choice, two caveats concerning the present study have to be kept in mind. First, the study contains only one country, Denmark. The possible influence of the country’s multiparty political system has already been noted, but apart from that there appears to be nothing in particular about Danish politics that should raise suspicion that the results cannot be generalized to other countries. The replication, in the analyses, of findings by both Walgrave et al. (2012) and Therriault (2009) supports this assertion. Second, the study also only included four issues. While these have been selected on specific theoretical grounds set out above, it is necessary to raise the possibility that issue specific logics may be at play. The possible implications of such logics are illustrated by the fact that results on the immigration issue, on occasion, deviate somewhat from those on the other three issues. On immigration, thus, one party – the Danish People’s Party – is so strongly associated with the issue that there is very little variation in answers to the spontaneous and emphasis versions. Crucially, however, the overall pattern of results on the issue follows those found on the other issues. To explore the generality of this finding, future studies might include more issues with similarly clear ownership configurations. 20 References Bélanger, Éric and Bonnie M. Meguid (2008). "Issue salience, issue ownership, and issue-based vote choice", Electoral Studies, 27:3, 477-91. Bellucci, Paolo (2006). "Tracing the cognitive and affective roots of 'party competence': Italy and Britain, 2001", Electoral Studies, 25:3, 548-69. Beyer, Audun, Carl H. Knutsen and Bjørn E. Rasch (2014). "Election Campaigns, Issue Focus and Voting Intentions: Survey Experiments of Norwegian Voters", Scandinavian Political Studies. Brandenburg, Heinz (2005). "Political Bias in the Irish Media: A Quantitative Study of Campaign Coverage during the 2002 General Election", Irish Political Studies, 20:3, 297-322. Budge, Ian and Dennis Farlie (1983). "Party Competition - Selective Emphasis or Direct Confrontation? An Alternative View with Data", in Hans Daalder and Peter Mair (eds.), Western European Party Systems. Continuity & Change. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 267-305. Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes (1960). The American Voter. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Dolezal, Martin, Laurenz Ensser-Jedenastik, Wolfgang C. Müller and Anna K. Winkler (2013). "How parties compete for votes: A test of saliency theory", European Journal of Political Research. Egan, Patrick J. (2013). Partisan Priorties. How Issue Ownership Drives and Distorts American Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Geys, Benny (2012). "Success and failure in electoral competition: Selective issue emphasis under incomplete issue ownership", Electoral Studies, 31:2, 406-12. Green, Jane and Sara B. Hobolt (2008). "Owning the issue agenda: Party strategies and vote choices in British elections", Electoral Studies, 27:3, 460-76. Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (2007). "The Growing Importance of Issue Competition: The Changing Nature of Party Competition in Western Europe", Political Studies, 55:4, 608-28. Green-Pedersen, Christoffer and Rune Stubager (2010). "The Political Conditionality of Mass Media Influence. When do Parties Follow Mass Media Attention?", British Journal of Political Science, 40:3, 663-77. Karlsen, Rune and Bernt Aardal (2011). "Kamp om dagsorden og sakseierskap", in Bernt Aardal (ed.), De politiske landskap. En studie af stortingsvalget 2009. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk, 131-62. Kuechler, Manfred (1991). "Issues and voting in the European Elections 1989", European Journal of Political Research, 19:1, 81-103. Martinsson, Johan (2009). Economic Voting and Issue Ownership. An Integrative Approach. Gothenburg: Department of Political Science,University of Gothenburg. Meguid, Bonnie M. (2005). "Competition between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success", American Political Science Review, 99:3, 347-59. 21 Meyer, Thomas M. and Wolfgang C. Müller (2013). "The Issue Agenda, Party Competence and Popularity: An Empirical Analysis of Austria 1989-2004", Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. Narud, Hanne M. and Henry Valen (2001). "Partikonkurranse og sakseierskap", Norsk Statsvitenskaplig Tidsskrift, 17:4, 395-425. Oscarsson, Henrik, and Sören Holmberg (2013). Nya svenska väljare. Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik. Petrocik, John R. (1996). "Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study", American Journal of Political Science, 40:3, 825-50. Schuman, Howard, and Stanley Presser (1996). Questions and Answers in Attitude Surveys. Expriments onQuestion Form, Wording, and Context. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Stokes, Donald E. (1963). "Spatial Models of Party Competition", American Political Science Review, 57:2, 368-77. Stokes, Donald E. (1992). "Valence Politics", in Dennis Kavanagh (ed.), Electoral Politics. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 141-64. Stubager, Rune (under review). "What Can a Party Do? Parties Potentials for Influencing Voters' Issue Ownership Perceptions". Stubager, Rune and Rune Slothuus (2013). "What are the Sources of Political Parties' Issue Ownership? Testing Four Explanations at the Individual Level", Political Behavior, 35:3, 567-88. Taber, Charles S. and Milton Lodge (2006). "Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs", American Journal of Political Science, 50:3, 755-69. Therriault, Andrew (2009). Issue Ownership, Party Reputations, and Policy Positions. Where Issue Ownership Comes From, and Why the Answer Matters. Unpublished paper. New York, NY: New Your University. Tresch, Anke, Jonas Lefevre and Stefaan Walgrave (2013). "'Steal me if you can!': The impact of campaign messages on associative issue ownership", Party Politics. van der Brug, Wouter (2004). "Issue ownership and party choice", Electoral Studies, 23:2, 209-33. Wagner, Markus and Eva Zeglovits (2014). "Survey questions about party competence: Insights from cognitive interviews", Electoral Studies, 34:1, 280-90. Walgrave, Stefaan, Jonas Lefevre and Anke Tresch (2012). "The Associative Dimension of Issue Ownership", Public Opinion Quarterly, 76:4, 771-82. Wright, John R. (2012). "Unemployment and the Democratic Electoral Advantage", American Political Science Review, 106:4, 685-702. Zaller, John (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 22 Table 1. Issue ownership over Immigration and Tax Policy, Per Cent. Standard CIO LongTerm CIO ShortTerm CIO Best Policy Best Qualified Spontaneous AIO Immigration Social Democrats Social Liberals Conservatives Socialist People’s P. Liberal Allinace Christian Democrats Danish People’s P. Liberals Red-Green Alliance Equally Good/Bad Don’t know Duncan Index 14.2 8.4 1.4 4.6 1.6 0.4 33.5 9.8 6.0 8.9 11.3 16.7 8.1 2.2 2.9 0.8 0.6 25.7* 13.4* 4.9 12.4* 12.2 11.6 16.2 7.0 2.6 4.4 1.5 0.2 28.9 12.2 3.9 12.7* 10.5 9.4 10.9 8.8 2.9 5.9 2.7 0.2 31.5 7.4 12.0* 6.1 11.6 10.7 14.7 9.1 1.1 5.7 1.9 0.8 27.6* 10.2 8.5 10.2 10.2 7.3 5.4* 3.7* 0.6 1.7* 0.8 0.3 76.1* 1.9* 2.2* 5.5 1.7* 42.7 Tax Policy Social Democrats Social Liberals Conservatives Socialist People’s P. Liberal Allinace Christian Democrats Danish People’s P. Liberals Red-Green Alliance Equally Good/Bad Don’t know Duncan Index 17.9 4.7 4.3 2.8 5.6 0.3 5.1 25.6 4.7 15.1 14.0 22.0 4.3 5.7 1.4 1.2* 0.2 3.1 30.1 2.2* 14.9 14.9 11.0 19.3 6.1 4.1 2.2 4.4 0 3.5 28.2 3.3 17.7 11.2 8.1 17.6 5.9 5.3 4.6 7.4 0 5.0 21.6 7.6* 9.9* 15.1 9.9 21.4 6.8 5.1 3.6 4.5 0.6 4.7 23.1 5.3 15.5 9.5* 8.5 21.8* 4.6 8.3* 2.1 9.8* 0.1 3.2* 31.8* 1.7* 13.1 3.5* 18.4 Emphasis AIO 4.8*/ 4.1*/ 0.7 1.4*/ 0.8 0.2 68.2*/* 3.0*/* 5.3/* 3.2*/* 8.3/* 34.8 11.3 11.3*/* 3.8 10.7*/* 1.2*/ 16.6*/* 0 4.6/* 27.0/* 3.3/* 7.4*/* 13.9/* 19.0 22.7 N 788 491 543 476 529 2,180 1,454 Note: *: p < .05. CIO: Competence Issue Ownership; AIO: Associative Issue Ownership. Entries are percentages giving each answer. Significance tests compare the share in each cell with the corresponding cell for the Standard CIO version. In the last column, asterisks after the slash signify a difference between the two AIO versions. The Duncan index is calculated with respect to the Standard CIO version except the scores in the lower rows of the two halves of the table which relate to the difference between the two AIO versions. 23 Table 2. Issue ownership over Unemployment and the Danish Economy, Per Cent. Standard CIO LongTerm CIO ShortTerm CIO Best Policy Best Qualified Spontaneous AIO Unemployment Social Democrats Social Liberals Conservatives Socialist People’s P. Liberal Allinace Christian Democrats Danish People’s P. Liberals Red-Green Alliance Equally Good/Bad Don’t know Duncan Index 21.1 2.8 1.3 4.2 2.9 0.3 5.3 18.4 8.9 21.1 13.8 32.6* 2.2 2.0 3.3 1.0* 0.2 2.0* 23.2* 4.3* 14.9* 14.3 17.6 23.8 3.1 1.8 2.0* 2.8 0.2 2.4* 21.4 8.7 23.2 10.7 8.6 19.3 5.3* 2.5 5.5 3.2 0 5.0 15.5 14.1* 13.7* 16.0 12.7 23.1 5.1* 1.5 3.8 4.2 0.6 4.2 16.4 11.3 19.1 10.8 8.5 40.3* 1.3* .6 3.9 2.0 0.1 3.1* 12.8* 14.0* 18.9 3.0* 24.4 The Danish Economy Social Democrats Social Liberals Conservatives Socialist People’s P. Liberal Allinace Christian Democrats Danish People’s P. Liberals Red-Green Alliance Equally Good/Bad Don’t know Duncan Index 19.7 6.6 2.8 1.4 3.2 0.4 5.3 28.8 3.3 16.4 12.2 23.6 6.3 7.1* 0.4 1.0* 0.2 1.8* 33.8 2.2 13.4 10.0 13.4 21.0 6.8 3.1 1.3 2.8 0.2 3.1 29.3 3.1 18.0 11.2 4.0 21.0 9.0 3.2 2.9 3.4 0 5.0 26.1 4.6 9.5* 15.3 10.3 21.2 8.1 2.8 1.3 4.0 0.6 3.6 26.5 4.0 17.0 11.0 5.3 28.6* 8.9 2.7 0.7* 3.0 0.1 3.3* 31.4 2.0* 16.2 3.1* 13.9 Emphasis AIO 19.0/* 1.8 1.7/* 5.3/* 2.6 0.1 6.4/* 10.2*/* 29.5*/* 11.0*/* 12.5/* 23.2 31.9 17.2/* 8.4 4.3*/* 0.7 6.6*/* 0.1 5.5/* 29.4 2.2 12.4*/* 13.3/* 8.6 17.8 N 788 491 543 476 529 2,180 1,454 Note: *: p < .05. CIO: Competence Issue Ownership; AIO: Associative Issue Ownership. Entries are percentages giving each answer. Significance tests compare the share in each cell with the corresponding cell for the Standard CIO version. In the last column, asterisks after the slash signify a difference between the two AIO versions. The Duncan index is calculated with respect to the Standard CIO version except the scores in the lower rows of the two halves of the table which relate to the difference between the two AIO versions. 24 Table 3. Predispositions and Issue Ownership, McFadden’s R2. Standard CIO Long Term CIO ShortTerm CIO Best Policy Best Qualified Spontaneous AIO Emphasis AIO Immigration Empty model 12.4 13.8 14.0 6.6 9.2 61.3 55.5 Full model 57.8 48.9 57.3 61.1 60.6 63.4 60.8 Difference 45.4 35.1 43.3 54.5 51.4 2.1 5.3 Tax Policy Empty model 16.3 30.6 20.3 7.5 13.5 19.6 15.9 Full model 67.2 59.4 63.7 63.8 59.4 23.2 25.8 Difference 50.9 28.8 43.4 56.3 45.9 3.6 9.9 Unemployment Empty model 17.5 34.6 22.5 11.4 14.1 32.3 20.1 Full model 61.0 64.2 65.3 58.2 63.5 33.9 41.7 Difference 43.5 29.6 42.8 46.8 49.4 1.6 21.6 The Danish Economy Empty model 22.4 32.5 25.3 18.7 20.9 28.7 18.9 Full model 70.8 63.2 71.1 66.5 68.1 44.3 48.4 Difference 48.4 30.7 45.8 47.8 47.2 15.6 29.5 Note: CIO: Competence Issue Ownership; AIO: Associative Issue Ownership. Entries are explained variance as measured by McFadden’s R2 from conditional logit models multiplied by 100. The empty models include only party intercepts whereas the full models add party identification and policy agreement between respondents and the parties. Both independent variables are significant at the .05-level in all models and, hence, so are all differences between the empty and full models. 25