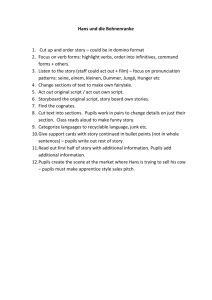

HP Programme - Implementation Science

advertisement