The Missing Dimension - The Center for Process Studies

advertisement

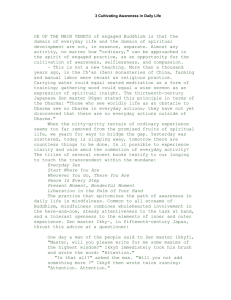

Stephen Rowe, Dispatches – From the Contest of American Culture in Education 9/24/14 1075 THE MISSING DIMENSION : There is a rather large cluster of terms that appear, often together and sometimes interchangeably, in the discourse of American higher education today: mindfulness, critical thinking, service, diversity, attentiveness, contemplation, reflection, meditation, otherness, reflexivity, inclusiveness, integration, multiculturalism, and dialogue. These terms, both separately and in various combinations, are often associated with the highest order of importance and possibility. But what do they mean? This question is rarely asked because the terms radiate significance, almost an energy, and because few want to slow down the parade by admitting ignorance. So we stumble along in an atmosphere of both enthusiastic acknowledgment and considerable confusion. This is the condition I want to address in this essay, by proposing a simple distinction between three interdependent developmental stages and levels through which these terms can be understood and advanced within the rich but often muddled discourse of education in our time. Confusion arises in large part because all of these terms are reflective of distinctly postmodern sensibilities and intuitions, glimmers of a way of knowing and being that is deeper than the modern dichotomies between idealistic intellectualism and positivistic empiricism, fact and value, objective and subjective. They arise from the sense that there is something more than either absolute/ideological Truth or relativistic personal preference, something we can be in 1 touch with and live well by. It is precisely the absence of these sensibilities and intuitions – of something deeper or more than the prevailing modern mindset and its institutionalization in our educational systems could envision – that led the great social ethicist, James Luther Adams, to conclude that this absence was a primary reason for the failure of 1960’s activism. His term for what was missing was “disciplines of the inner life.”i Could it be that now, nearly fifty years later, we are experiencing the emergence of a post-modern worldview? So my largest thesis is that in the space between the poles of modern dichotomous (or Cartesian) thinking we see on the contemporary landscape of higher education three levels of the inner life being reawakened and engaged. In am proposing that the rather long list of terms in the first lines of this essay can be organized and understood in these three levels and developmental stages, in a world where the nautilus shell is a more adequate image than the straight line. The first is Dialogue. Moving beyond the dichotomy of rote learning and propositional logic versus assertions of unexamined personal preference, this capacity entails the capacity for understanding and “reflection” on a variety of positions – including one’s own – on any given issue, as well as the ability to be open to emergent truth as an essential property of dialogue, democratic relationship, or mature thinking. It indicates the ability to thrive in a “pluralistic” environment where encounter with the “other” is welcomed as opportunity rather than threat, where “diversity,” “inclusiveness,” and “multiculturalism” are positive values. Is this not precisely what Socrates had in mind when he advocated “the examined life” (Apology, 38a)? The life he advocated is associated with contemporary usages of “reflexivity” and “critical thinking” as something greater than the ability to recognize bad logic and/or manipulation. 2 The second is Meditation. Moving beyond the dichotomy between theoretical and practical knowing, here we are talking about engagement of a practice which allows us to live with openness to deep sources of knowing, and the capacities of “mindfulness” and “reflexively. It cultivates a way of presence referred to as “attentiveness” through contemplative practice. The world and its varied traditions contain many such practices with remarkable similarities and differences. Essentially they involve the paradox of clearing one’s mind and thinking nothing, with the aid of a very specific object of focus (or “mantra”). These practices are often simple though not easy. Though there can be many arguments about the true nature of this practice of meditation, none of them are very fruitful apart from the actual experience of doing it, which turns out to be extremely persuasive in terms of stress reduction, emotional stability, concentration, and quality of presence which follow from its engagement. Persuasiveness is aided by the recent findings of neuroscience, as well as continuing reappropriations of those mystical traditions which were dismissed in the tempest of modernity. Third is Service. Moving beyond the dichotomy between self-interest and self-sacrifice, real “service learning” is centered on a point that is well understood by the great traditions: that the end of meditation is to stop “meditating” as a separate and distinct practice. The end is to be meditating all the time, to “return,” as an old Zen proverb says very compactly: “Easy to meditate in the monastery, more difficult in the home, most difficult in the world.” To be meditating all the time is to be in caring or compassionate relationship with the other, such that this quality of relationship – indicated by the Greek love of the world (amour mundi), the Christian “love thy neighbor as thyself,” and the Japanese Zen identification of prajna (wisdom) 3 with karuna (compassion) – becomes both the mark of true enlightenment and the finest form of practice. Service as also associated with the wholeness of the person, and hence the “integrative” dimension of education, where everything we have studied and become is brought to the essential moment of our presence in the world. So I am here proposing simple clarification of some of the more sensitive terminology of our time, but I am also seeking to illuminate a developmental pathway which some of our more exemplary students travel in the direction of becoming the kind of adults we so urgently need. However, clarification must be followed by a caution, especially when developmental movement is involved. As we practice the teaching art through which we guide students, we must be careful not to let levels and stages fall into yet another simple linearity, a risk that runs very high in an era of assessment, quantification, and standardization. The feminist and philosopher of education, Elizabeth Minnich, reminds us of the importance of honoring complexity and interdependence: “… I want to make a case for an overlap of thoughtfulness and mindfulness as arts and ways of being for which we can purposefully educate, not as in some traditions to win release from the world but, entirely on the contrary, to accept our responsibilities as conscious beings affected by and affecting the worlds around us with every breath, action, and word.”ii So reclaiming the depth dimension of a cultivated inner life is not an entirely private matter, and neither is it opposed to thought and action in the world. i James Luther Adams, “The Changing Reputation of Human Nature,” in Voluntary Associations: Socio-Cultural Analysis and Theological Interpretation, ed. J. Ronald Engel (Chicago: Exploration Press, 1986), p. 31. ii Elizabeth Minnich, “The Evil of Banality: Arendt Revisited,” in Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 0(0). P. 5. 4