Objective: To determine the incidence of pulmonary embolism in

advertisement

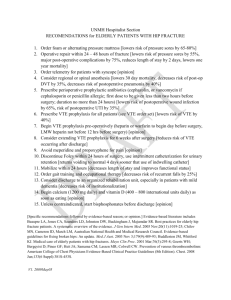

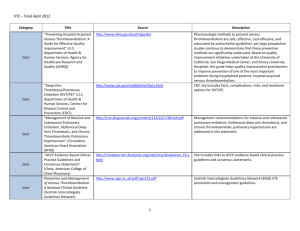

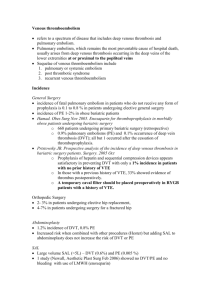

Objective: To determine the incidence of pulmonary embolism in surgical mortality patients in Australia and assess the appropriateness of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis usage. Introduction VTE remains a major cause of morbidity and a significant cause of mortality in hospitalized patients across Australia each year. The common presentations of VTE include deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the lower limbs and pulmonary embolism (PE). VTE has an average annual incidence of 30,000 cases in which an estimate of 7% die (ref). PE is diagnosed in10% of all hospitalized patients (1, 2), possibly being one of the most common preventable causes of inhospital deaths (3, 4). Studies have shown that there is a strong linkage between the occurrence of DVT and PE. About 50% of patients with proximal DVT develop PE while 30% of patients with DVT, independent of location, develop post-thrombotic syndrome or recurrent DVT as a consequence. On the other hand, 70% of those with clinically significant PE have had a history of DVT (5-7). Hospitalised patients have markedly increased risk of developing these presentations than the rest of the community (8). In the absence of prophylaxis, the rates of DVT and fatal PE among general surgical patients range from 15-30% and 0.2 to 0.9% respectively(9, 10).The rate of DVT in vascular surgery is approximately 21% with routine contrast venography (11-13)and 15% with routine postoperative ultrasonography performed(14, 15). In total hip replacements, the incidence of venographydetected DVT ranges from 40% to 60% and clinically overt VTE between 2% and 5%(10, 16)while fatal PE occurs in approximately 1 of 500 patients undergoing elective hip replacement(17, 18). The pathogenesis of VTE is proposed by Virchow’s triad of hypercoagulability, blood stasis and vascular endothelial injury which leads to thrombosis(19). Virchow demonstrated that pulmonary thrombi from deep veins of the systemic circulation are carried to the pulmonary circulation by venous blood flow (10). Several studies showed that many patients fulfil all, or most of the criteria of Virchow’s Triad (11, 12, 13). Various medical risk factors have been identified to cause VTE in hospitalised patients. These include more than 48 hours of immobility Prepared by Siang Wei GAN, Sarah LEE 2012 in the preceding month, surgery, malignancy, infection in the past three months and hospitalisation. Many patients with an episode of VTE, have more than one of these risk factors(20). Furthermore it is believed that the interaction between multiple coexisting risk factors contribute to the increased risk of developing VTE regardless of the risk factors (4, 21). In addition, the presence of a positive family history contributes to be a strong risk factor for developing VTE(22). Method of DVT/PE detection DVT is diagnosed clinically and confirmed by compression ultrasonography. Ascending venography is considered to be the ‘gold standard’ diagnostic tool with a greater sensitivity than compression ultrasound for distal (below-knee) DVT. However, it is rarely used in clinical practice due to its invasive technique. PE is usually diagnosed or excluded by computed tomographic (CT), pulmonary angiography or ventilation-perfusion isotope scan. Screening for PE is not routinely performed, however patients are assessed for PE based on clinical suspicion, symptoms, signs and other investigations. Therefore, the actual incidence of PE may be underestimated(23). Among surgical patients, the overall risk of VTE relies on both the patient’s baseline morbidities and the nature of the surgery including type of surgery, duration and type of anaesthesia(24, 25). Procedures with an especially high risk of developing VTE immediately after surgery are orthopaedic surgery, major vascular surgery and neurosurgery(26).The absolute risk of DVT in hospitalised patients without thromboprophylaxis is approximately 10-40% among general surgery patients, and 40-60% among major orthopaedic patients(27). In addition, there is an increasing awareness that VTE risk among those surgical patients persists for several weeks after hospital discharge, for example hemiarthroplasty of hip fracture and knee replacement surgery (28-30). Studies revealed that VTE prophylaxis used in surgical patients is suboptimal, inconsistently applied and underutilised (31-33). In certain cases where prophylaxis was prescribed to surgical patients, the duration of administration is often inadequate, resulting in a high incidence of post discharge VTE Prepared by Siang Wei GAN, Sarah LEE 2012 events(33, 34). In the United States, appropriate prophylaxis is based on the 2001 American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines for correct type, dose and duration. These guidelines identified that correct procedures were followed in only 32% of all surgical patients and ranged from 12% of neurosurgery patients to 74% of orthopaedic surgery patients(26, 30, 34). Due to the silent features of DVT, only 19% of patients had symptoms of DVT before death in a study conducted in the UK (35). In a Swedish study, out of 994 autopsies that were performed from departments of general surgery, infectious diseases, internal medicine, oncology and orthopaedics, 347 patients (35%) were found to have VTE(36). This shows that incidence of PE may be underestimated(23). Therefore, effective VTE risk assessment is crucial in identifying patients that are at high risk in order to optimise the use of prophylaxis which in turn improves patient outcomes(37). VTE prophylaxis has been identified as being inappropriately or under-prescribed in a significant number of patients(38, 39) therefore, various risk assessment guidelines have been produced to help reduce the incidence of VTE (40). The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Clinical Practice Guideline listed a number of well-recognised VTE risk factors which include age, previous VTE, active or occult malignancy and marked obesity. The patients are not divided into low or high risk categories based on any single risk factor or combination of risk factors due to lack of supporting evidence in the literature. The guideline recommends that the use of prophylaxis should be a clinical decision based on the presence of individual risk factors(23). The Thromboembolic Risk Factors (THRIFT) Consensus Group recently produced a guideline to classify patients into three groups based on the degree of risk of VTE. Low risk patients have a less than 10% chance of developing DVT, while moderate and high risk patients have a 10-40% and 40-80% chance respectively (39, 41, 42). Due to difficulties and complexities in individualising each patient's thromboprophylaxis regime which may cause suboptimal therapeutic effect, the 2008 ACCP Guidelines have grouped patients into low, moderate or high risk groups depending on the risk factors and the type of surgeries performed(24). Prepared by Siang Wei GAN, Sarah LEE 2012 Evidence of the use of VTE Prophylaxis protocols There are various methods of VTE prophylaxis that are commonly used in Australia which include pharmacological and mechanical prophylaxis. The optimum agent of prophylaxis should be effective, administered easily, have a predictable onset and duration with minimal food or drug interactions besides being easily reversible and be cost effective with minimal side effects (43). Various studies have attempted to look into the efficacy of the different prophylaxis agents. However there is no conclusive evidence to show which agent is more superior. A review by Amaragiri and Lees showed that graduated compression stocking reduced the risk of DVT in hospitalised patients after their operation, but had an even better result when coupled with another agent (44). However, at least 18 to 20 hours a day is needed for mechanical prophylaxis to be effective which is difficult to achieve due to poor compliance by patients (45). The Pulmonary Embolism Prevention trial showed that aspirin significantly decreased the risk of DVT and PE by 37% and 53% respectively in 26,890 high risk medical, general surgical and orthopaedic patients when compared to placebo (46). Aspirin is not part of VTE prophylaxis recommendation from ACCP Guidelines due to its safety profile and low efficacy (24) however the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical guidelines have included aspirin as one of the recommended VTE prophylaxis agents (47). On the other hand, a meta-analysis demonstrated that compared to placebo, unfractioned heparin managed to reduce the risk of DVT by 68% in general surgical, orthopaedic and urological surgical patients (48). There is no specific protocol of VTE prophylaxis for emergency surgery in the current Australian guidelines(23). However, patients that are admitted emergently to the surgical ward are thought to have a moderate risk of developing VTE(49).Emergency caesarean section is identified as an independent risk factor of postnatal VTE (odds ratio of 2.7, 95% confidence interval 1.8-4.1)(50) as it confers the patient a two-fold chance of developing VTE compared to a planned caesarean section. A UK study also concluded that patients admitted as an emergency were less likely to receive adequate thromboprophylaxis(42). An alternate study showed that hospitalised surgical patients following abdominal surgery were found to receive inadequate VTE prophylaxis(51). This is supported by a Canadian study where only 56.9% of patients admitted emergently to the surgical ward with acute abdominal conditions received adequate prophylaxis even though they had a higher risk of VTE (33). While there has not been many trials looking into the use of Prepared by Siang Wei GAN, Sarah LEE 2012 prophylaxis for patients having emergency surgery, the evidence shows that the use of prophylaxis helps to prevent the development of VTE in patients admitted with acute medical conditions. Pearsall et al (2010) suggested the results of these studies are applicable to surgical patients as many surgical patients have the same comorbidities and risk factors as do medical patients(49). Conclusion In summary, VTE is a major public health issue, predominantly among the surgical patients, regardless of administration of VTE prophylaxis as suboptimal usage and inadequate duration of prophylaxis used, has always been a problem. The development of Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines for Prevention of VTE has highlighted gaps which suggest areas for future research, including: knowledge relating to the prevalence of known risk factors for VTE and the magnitude of risk, and evidence on the effectiveness of VTE prevention in specific situations. Lastly, there is a lack of studies conducted on emergency admissions requiring surgery and the role of VTE prophylaxis in this setting, along with the absence of a specific protocol for VTE prophylaxis in Australia. However, in Adelaide there are hospital-wide protocols but even these set of guidelines differ from hospital to hospital. For example, the Royal Adelaide Hospital allows the use of heparin in moderate risk patients undergoing surgery (52) while the Queen Elizabeth Hospital only approves the use of enoxaparin in moderate risk patients (53). Therefore, it would be worth investigating the VTE disease in emergency operative procedures of surgical mortality patients in Australia and the corresponding VTE prophylaxis regimen used, if any and their respective efficacies. Prepared by Siang Wei GAN, Sarah LEE 2012 References 1. Ho WK, Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW. The incidence of venous thromboembolism: a prospective, community-based study in Perth, Western Australia. Med J Aust. 2008 Aug 4;189(3):144-7. 2. Studies NIoC. Evidence-Practice Gaps Report: National Institute of Clinical Studies2003. 3. Alikhan R, Peters F, Wilmott R, Cohen AT. Fatal pulmonary embolism in hospitalised patients: a necropsy review. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2004 Dec;57(12):1254-7. 4. Geerts W, Ray JG, Colwell CW, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Lassen MR, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2005;128(5):3775(2). 5. Prandoni P, Lensing AWA. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. [Article]. 1996;125(1):1. 6. Bick RL, Fareed J. Current Status of Thrombosis: A Multidisciplinary Medical Issue and Major American Health Problem—Beyond the Year 2000. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 1997 October 1, 1997;3(1 suppl):S1-S5. 7. A.B. ADAN. Thrombosis and Coagulation: Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism Prophylaxis. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2005;85(6):1163-77. 8. Heit JA, Melton LJ, Lohse CM, Petterson TM, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients vs community residents. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001 Nov;76(11):1102-10. 9. Mismetti P, Laporte S, Darmon JY, Buchmüller A, Decousus H. Meta-analysis of low molecular weight heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in general surgery. Brit J Surg. 2001;88(7):913-30. 10. Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, Pineo GF, Colwell CW, Anderson FA, et al. Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism. Chest. 2001 January 1, 2001;119(1 suppl):132S-75S. 11. Hamer JD. Investigation of oedema of the lower limb following successful femoropopliteal bypass surgery: The role of phlebography in demonstrating venous thrombosis. Brit J Surg. 1972;59(12):979-82. 12. Porter JM, Lindell TD, Lakin PC. Leg Edema Following Femoropopliteal Autogenous Vein Bypass. AMA Arch Surg. 1972 December 1, 1972;105(6):883-8. 13. Olin JW, Graor RA, O'Hara P, Young JR. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm resection. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 1993;18(6):1037-41. 14. Hollyoak M, Woodruff P, Muller M, Daunt N, Weir P. Deep venous thrombosis in postoperative vascular surgical patients: A frequent finding without prophylaxis. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2001;34(4):656-60. 15. Killewich LA, Aswad MA, Sandager GP, Lilly MP, Flinn WR. A Randomized, Prospective Trial of Deep Venous Thrombosis Prophylaxis in Aortic Surgery. Arch Surg. 1997 May 1, 1997;132(5):499-504. 16. Salvati EA, Pellegrini VD, Sharrock NE, Lotke PA, Murray DW, Potter H, et al. Recent Advances in Venous Thromboembolic Prophylaxis During and After Total Hip Replacement. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, American Volume. [Article]. 2000;82(2):252. 17. Warwick D, Williams M, Bannister G. Death and thromboembolic disease after total hip replacement. A series of 1162 cases with no routine chemical prophylaxis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995 January 1, 1995;77-B(1):6-10. 18. Wroblewski BM, Siney PD, Fleming PA. Fatal pulmonary embolism after total hip arthroplasty: diurnal variations. Orthopedics. 1998;21(12):1269-71. 19. Bagot CN, Arya R. Virchow and his triad: a question of attribution. Brit J Haematol. 2008 Oct;143(2):180-90. Prepared by Siang Wei GAN, Sarah LEE 2012 20. Spencer FA, Emery C, Lessard D, Anderson F, Emani S, Aragam J, et al. The Worcester venous thromboembolism study - A population-based study of the clinical epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Jul;21(7):722-7. 21. Anderson FA, Jr., Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. [Review]. 2003 Jun 17;107(23 Suppl 1):I9-16. 22. Bezemer ID, van der Meer FJ, Eikenboom JC, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. The value of family history as a risk indicator for venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2009 Mar 23;169(6):610-5. 23. Council NHaMR. Clinical Practice Guideline For the Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients Admitted to Australian Hospitals. National Health and Medical Research Council; 2009. 24. Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Samama CM, Lassen MR, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. [Practice Guideline]. 2008 Jun;133(6 Suppl):381S-453S. 25. Jaffer AK, Barsoum WK, Krebs V, Hurbanek JG, Morra N, Brotman DJ. Duration of Anesthesia and Venous Thromboembolism After Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005 June 1, 2005;80(6):732-8. 26. White RH, Zhou H, Romano PS. Incidence of symptomatic venous thromboembolism after different elective or urgent surgical procedures. Thromb Haemostasis. [Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.]. 2003 Sep;90(3):446-55. 27. Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Bergqvist D, Lassen MR, Colwell CW, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism.(The Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy). Chest. 2004;126(3):338S(63). 28. Muntz J. Duration of deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis in the surgical patient and its relation to quality issues. Am J Surg. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review]. 2010 Sep;200(3):413-21. 29. Dahl OE, Andreassen G, Aspelin T, Muller C, Mathiesen P, Nyhus S, et al. Prolonged thromboprophylaxis following hip replacement surgery--results of a double-blind, prospective, randomised, placebo-controlled study with dalteparin (Fragmin). Thromb Haemostasis. [Clinical Trial Randomized Controlled Trial]. 1997 Jan;77(1):26-31. 30. Huber O, Bounameaux H, Borst F, Rohner A. Postoperative Pulmonary-Embolism After Hospital Discharge - An Underestimated Risk. Arch Surg. [Article]. 1992 Mar;127(3):310-3. 31. Tooher R, Middleton P, Pham C, Fitridge R, Rowe S, Babidge W, et al. A systematic review of strategies to improve prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospitals. Ann Surg. [Meta-Analysis Review]. 2005 Mar;241(3):397-415. 32. Studies NIoC, Health AN, Council MR. Evidence-practice gaps report, volume 1: a review of developments 2004-2007: National Institute of Clinical Studies; 2008. 33. Yu HT, Dylan ML, Lin J, Dubois RW. Hospitals' compliance with prophylaxis guidelines for venous thromboembolism. Am J Health Syst Pharm. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2007 Jan 1;64(1):69-76. 34. Amin AN, Stemkowski S, Lin J, Yang G. Preventing venous thromboembolism in US hospitals: are surgical patients receiving appropriate prophylaxis? Thromb Haemostasis. [Letter Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2008 Apr;99(4):796-7. 35. Sandler DAM, J.F. Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1989;82(4):203-5. Prepared by Siang Wei GAN, Sarah LEE 2012 36. Lindblad B, Sternby NH, Bergqvist D. Incidence of venous thromboembolism verified by necropsy over 30 years. British Medical Journal. 1991;v302(n6778):p709(3). 37. Bergan JJ. The vein book: Elsevier Academic Press; 2007. 38. Stratton MA, Anderson FA, Bussey HI, Caprini J, Comerota A, Haines ST, et al. Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism: Adherence to the 1995 American College of Chest Physicians Consensus Guidelines for Surgical Patients. Arch Intern Med. 2000 February 14, 2000;160(3):334-40. 39. Harinath G, St John PH. Use of a thromboembolic risk score to improve thromboprophylaxis in surgical patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1998 Sep;80(5):347-9. 40. Colditz G, Tuden R, Oster G. Rates of Venous Thrombosis After General Surgery: Combined Results Of Randomised Clinical Trials. The Lancet. 1986;328(8499):143-6. 41. Scurr J, Baglin T, Burns H, Clements RV, Cooke T, de Swiet M, et al. Risk of and prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospital patients. Phlebology. [Review]. 1998;13(3):87-97. 42. Gillies TE, Ruckley CV, Nixon SJ. Still missing the boat with fatal pulmonary embolism. Brit J Surg. 1996 Oct;83(10):1394-5. 43. Zywiel MG JA, Mont MA. DVT prophylaxis: better living through chemistry: opposes. Orthopedics. 2010;33(9). 44. Sachdeva A DM, Amaragiri SV, Lees T. Elastic compression stockings for prevention of deep vein thrombosis. 2010. 45. Michota FA. Prevention of venous thromboembolism after surgery. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2009 November 1, 2009;76(Suppl 4):S45-S52. 46. Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial. The Lancet. 2000;355(9212):1295-302. 47. Surgeons AAoO. AAOS Clinical Guideline on Prevention of Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism (PE) in Patients Undergoing Total Hip or Knee Arthroplasty. 2007. 48. Collins R, Scrimgeour A, Yusuf S, Peto R. Reduction in Fatal Pulmonary Embolism and Venous Thrombosis by Perioperative Administration of Subcutaneous Heparin. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;318(18):1162-73. 49. Pearsall E, Sheth U, Fenech D, McKenzie M, Victor J, McLeod R. Patients Admitted with Acute Abdominal Conditions are at High Risk for Venous Thromboembolism but Often Fail to Receive Adequate Prophylaxis. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2010;14(11):1722-31. 50. Jacobsen AF, Skjeldestad FE, Sandset PM. Ante- and postnatal risk factors of venous thrombosis: a hospital-based case–control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(6):905-12. 51. Amin AN, Lin J, Ryan A. Need to improve thromboprophylaxis across the continuum of care for surgical patients. Adv Ther. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2010 Feb;27(2):81-93. 52. Hospital RA. DVT prophylaxis for patients undergoing surgery. 2003. 53. Hospital TQE. DVT prophylaxis for patients undergoing surgery. 2005. Prepared by Siang Wei GAN, Sarah LEE 2012