Media Release

advertisement

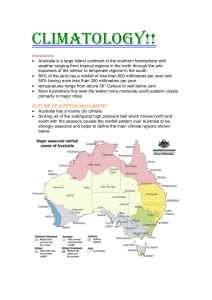

Climate change’s growing strain on Australian water resources EMBARGO: 2am, Tuesday, October 20. AEST Sydney, Australia: Satellite observations reveal plants in Australia’s semi-arid and sub tropical/ Mediterranean-style regions are getting greener because of increased atmospheric CO2, but at a significant cost to water resources. The more vigorous growth of plants requires more water, so less run-off now flows into many of Australia’s river basins, according to new research published in Nature Climate Change. “To compound matters, many important regions are projected to experience future declines in rainfall as a result of climate change,” said lead author Dr Anna Ukkola, who performed the research at the Department of Biological Sciences at Macquarie University, but is now based at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science. “This means water resources for agriculture and environmental flows in places like the Murray Darling Basin, inland Queensland and south-western Western Australia’s wheatbelt will be reduced even further.” But there was also a positive side to the greening. The researchers found, because of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide, less water was required to produce the exact same amount of leafy vegetation. This is because plants use water more efficiently where there is more carbon dioxide. So, for the same amount of water plants grew more vigorously which, in turn, likely increased the amount of carbon dioxide they took out of the atmosphere. According to the researchers, satellite measurements suggested areas of Australia with sufficient water resources were indeed showing an increase in vegetation. “This increased production is a boon for farmers where water resources are readily available, but the problem is for those regions that already experience water scarcity on a regular or semi-regular basis and where farmers rely on streamflow for irrigation needs,” Dr Ukkola said. As droughts regularly show us, once rainfall drops below a minimum level, plant growth slows and, if water scarcity is severe enough, they die. “The role of vegetation makes predicting future water resources difficult at best,” said coauthor Dr Trevor Keenan from the Department of Biological Sciences at Macquarie University. “We are however getting a better picture of likely possible futures for vegetation, water resources, and the impact of climate change on society in Australia.” As part of getting a clearer understanding, the researchers quantified the threshold at which there is enough rainfall to maintain a level of plant growth not restricted by a lack of water. They refer to this as the precipitation threshold. Above that threshold, there is no lack of water to restrict growth. Below that threshold, the lack of water impacts plant growth. Interestingly, observations from 1982-2010 show that as atmospheric carbon dioxide has increased over Australia and made plant growth easier, the precipitation threshold has declined. From 1982-1990, an average of around 900mm of rainfall a year was required for plants to grow without being restricted by a lack of water. From 2001-2008, the average amount had dropped to around 750mm a year. “While there are clearly some positives for growth found by this research, it also shows us that some of our crucial agricultural areas will not see these benefits because of the future impacts of climate change on rainfall,” said Dr Ukkola. “Water is the liquid gold that powers our economy, agriculture and daily lives now and into the future. At its core this research shows we must focus on how to preserve our water resources as our world changes.”