File

advertisement

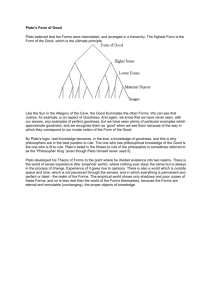

Finn 1 Contrasting Western and Eastern Philosophical Views Jordan Finn Nicholas Brasovan Philosophy 1330 5 December 2013 Finn 2 Contrasting Western and Eastern Philosophical Views The Western and Eastern hemispheres of the world developed independently from one another which resulted in a significant difference in not just culture and way of life, but in way of thinking and philosophical beliefs as well. Philosophy was defined by Confucius as the love of learning. It adopts an attitude of curiosity and strongly encourages one to question everything. The two hemispheres adopted very different ways of thinking about the world and our existence, with Western thought focusing on a supernatural ultimate reality and Eastern thought focusing on the self-creating quality of nature. Plato sets the stage for the foundation of Western thought with his concept of metaphysical dualism and his Allegory of the Cave. Many subsequent philosophers followed Plato’s concept and each retains the theme of a supernatural supreme being. Doaist thought focuses on a more naturalistic concept in which the world is seen as an ongoing process which is self-generating and self-sustaining which can be contrasted to Plato’s idea of an overarching source of the world. These two philosophies contrast in way of the theory of the origin of the world and knowledge theories as well as many other aspects of concepts of nature. Plato’s Dualism Plato, student to Socrates, set the foundation for the general theme of Western thought when he adopted a concept of metaphysical dualism to explain the origins of the world and the nature of the existing world today. In his studies, Plato attributed the existence of the empirical world to a supernatural world which was independent and transcendent of the physical empirical world we live in. This metaphysical dualism refers to these two realms which make up the universe, the first being the empirical visible world which we sense through observation. The second realm is the Realm of Forms and Ideas which is perfect and transcendent of the sensory Finn 3 world. This realm is independent and supreme and exists separately from the world we live in, which is a dependent and imperfect reflection of the supernatural realm. This realm was Plato’s form of arché, the defining principle upon which everything depends on to exist, or the source of the world (Class lecture notes). Plato divided the realms by a line signifying their separation and attributed different qualities to the two realms, describing their differences but also their interconnectedness. The Realm of Forms and Ideas is invisible, eternal, necessary, and absolute. The empirical world is visible, temporal, immanent, and always changing. The empirical world depends upon the Forms and Ideas which are independent and project upon the empirical world, a mere copy of the supernatural realm. Without the supernatural Forms and Ideas, the empirical world would not exist. The mind is consistent with the empirical world, dependent and temporal, where the soul is cohesive with the Realm of Forms and Ideas, eternal and unchanging. The mind, like the empirical world, is dependent upon the soul. In his “Allegory of the Cave” drawn from his work The Republic, Plato draws out a metaphor between the difference and significance of the two realms and the difference between life in the cave and life outside. The allegory begins by describing a scene in which prisoners are kept inside a dark cave from childhood on and are chained so that they cannot look at each other or anything else other than the wall in front of them (Deutsch 300). A fire is burning behind these prisoners, as guards place puppets in front of the fire representing images of men and dogs and other everyday structures. The prisoners believe these shadows to be the actual structures the puppets represent and do not realize they are merely shadows (Deutsch 301). One prisoner is forcefully dragged out of the cave into the world above and is stunned by the sunlight which he must adjust to in order to see anything. The prisoner’s eyesight gradually adjusts and he is able to see the real forms of the shadows he once believed to be real. If the prisoner were to return to the Finn 4 dark cave, the other prisoners would not believe him and would be adamant to remain in the cave, as they would believe the prisoner’s eyesight to be ruined (Deutsch 302). The cave and the shadows on the wall represent the empirical world which is less real than the transcendent realm which is represented by the outside world and actual forms which the prisoner is able to see once out of the cave. The prisoners are content with the shadows, which they believe to be real, just as people are content with the empirical world they can observe and sense. Once the one prisoner is able to get out of the cave, he no longer believes the shadows to be real and realizes the truth of these outside forms. The prisoner coming out of the cave represents enlightenment and the realization of the Realm of Forms, transcending past the empirical world into the intelligible (Deutsch 302). The person who dragged the prisoner out of the cave serves as a representation of a teacher which can help enlighten one to the ultimate reality of the supernatural realm. The other prisoners do not believe this enlightened prisoner and chose to only believe what they can observe just as others stick to the empirical world and their own observations (Deutsch 302). When one can see the Realm of Forms and its supreme reality, one can then transcend the constrictions of the empirical world. Plato’s Legacy Plato’s concept of metaphysical dualism was carried on throughout the works of subsequent Western philosophers which carried on the concept of the dualistic nature of the world, always implying the existence of a supernatural realm or being. His works were incorporated into many different schools of thought, and had a resonating impact in the works of Christian philosophers as well as that of scientific philosophers as well. Such philosophers or thinkers which adopted a similar concept to Plato can be seen through the works of St. Augustine Finn 5 and St. Thomas Aquinas, two early Christian philosophers which adopted a dualistic theory concerning religious matters. In Augustine’s work, “Evil as the Privation of Good”, Plato’s concept can be seen throughout his ideas which take on a dualistic attitude to the concept of goodness. Augustine asserts that all beings have goodness in them, for “the Creator of them all is supremely good” (Augustine 291). Evil is seen as merely the absence of this good for, like the Realm of Forms projects imperfect copies which make up the empirical world, the Creator produces imperfect projections as well. These individuals made after the Creator can then have less good “for they are not, like their Creator, supremely and unchangeably good” (Augustine 291). Just as the empirical world is not eternal and unchanging like the Realm of Forms, the individuals on Earth are not unchangingly good like their transcendent Creator. Augustine also alludes to Plato’s concept that the empirical world is dependent upon the Forms and Ideas through his idea that every being is dependent upon the good which can stand alone. But for good to be diminished is an evil, although, however much it may be diminished, it is necessary, if the being is to continue, that some good may constitute the being. For however small or whatever kind the being may be, the good which makes it a being cannot be destroyed without destroying the being itself (Augustine 291). The being cannot stand alone without the good whereas the good stands independent. The empirical world cannot stand alone without the Realm of Forms whereas the Realm of Forms, like Augustine’s concept of the good, is independent and eternal. Another Christian philosopher, St. Thomas Aquinas, incorporated Plato’s ideas into his works as well. Aquinas sought to prove the existence of God through using concepts very similar to Plato’s in his “Five Ways to Prove the Existence of God.” In one of his proofs, Aquinas goes off of Augustine’s study of good and asserts that the world is made up of a gradation of Finn 6 everything including good. Some beings are more or less good than others except for the ultimate good which was prior to all other goods which can be understood as God (Deutsch, 470). Plato’s ideas can be compared to this as the Realm of Forms and Ideas was prior to anything in the empirical world which are mere copies and projections of the Forms and Ideas. The projections in the empirical world can then also have a gradation of qualities, the only perfect quality being that Form. Another proof Aquinas presents is the fact that anything moved in the world must be moved by something else and that there must be a first mover. This first mover is what we understand to be God (Aquinas 471). Plato’s metaphysical dualism is seen in this concept, as the Realm of Forms is the first supreme mover, or source, which sets in motion the empirical world. Everything has a perfect Form in the Realm of Forms which can be thought of as the first and primary mover, the one substance to stand independent of anything else. Aquinas also presents a proof regarding efficient causes. No one thing on Earth can be the cause of itself. Just as in metaphysical dualism, nothing in the empirical world is dependent on only itself. What we understand as God is the first being to cause something else to exist which is prior to Himself, not being caused by anything else (Aquinas 470). The Realm of Forms is similarly independent and is the ultimate cause of the empirical world. Another proof is the fact that anything in existence exists through something else that was already in existence. Therefore something always had to be in existence and this is God (Aquinas 470). The Realm of Forms therefore is the supreme and eternal being which was always in existence and what is the source of all other things which make up the empirical world. Aquinas’s final proof deals with the concept of governance and the fact that unintelligent beings cannot move towards an end but we observe that they do in our world. Therefore, there must be some intelligent supreme being moving these things towards an end and that is God (Aquinas 471). Plato’s Realm of Forms can be seen as the Finn 7 supreme being which moves all things towards an end in the empirical world. Forms are perfect and are what which the empirical world depends to move towards an end. Chinese Naturalistic Cosmology Developing completely independent from the Western side of the world, the Eastern hemisphere produced a vastly different world view than that of Plato and his successors. Roger T. Ames, a philosophy professor at the University of Hawaii, asserts that the two civilizations “developed almost entirely independently of each other” (Ames 254) and that this produced “a far more profound difference in mental categories and modes of thought”(Ames 254), which then gave way to an entirely different philosophy. Plato’s concept of an arche, an ultimate principle by which all things exist, is opposed by the Chinese aesthetic view of the world and their belief that the world is always changing and “possesses its own creative energy”(Ames 255). The Chinese did not focus on an eternal and all powerful source of the universe, but instead looked to the universe and nature itself as a self-creating and self-governing source of energy. Chinese thinking focuses more on analyzing the source itself than searching for a supernatural principle which governs the order of the universe. This way of thinking ingrained in the Chinese prevented them from grasping the concept of Christianity, more alike to Plato’s concepts of an arche. Inversely, Western thinkers could not grasp the Chinese concepts of nature as a self-governing being (Ames 254). Because of the independent developments of the two separate cultures, the two philosophies have been contrasted and compared by several thinkers such as Ames. The Chinese school of Daoism exemplifies this naturalistic cosmology in such philosophical works as the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi along with the virtue of living a natural life dominated by simplicity and honesty. Daoist thinkers utilize the overall theme of ziran, Finn 8 meaning “self-so”, to expand upon the idea that the world possesses self-creating and selfgoverning qualities (Moeller 41). They believe the world was spontaneously created and that there is no precise Creation, but merely an origin of the world which remains a part of the whole, an on-going and always changing process. Daoist philosophy emphasizes the key concepts of determinacy and indeterminacy and their interconnectedness. Determinacy is correlated with presence as indeterminacy is correlated with absence. Presence is therefore rooted in absence. Writer Hans-Georg Moeller defines this concept of Daoism using the metaphor of the root when analyzing the Daodejing. Like the root, the Dao is indeterminate and like the plant, the universe is determinate. The metaphor expands on this concept by presenting the root as an origin of the universe but rejects the idea that the root is some supernatural divine force that created and governs the world (Moeller 40). Very different from Western views, Moeller goes on to explain that the creation of the world, “without an absolute beginning, is an on-going process of which its origin is an internal part” (Moeller 40). The metaphor explains that the Doa is the root of the world and is a continuous part of this self-generating and constant process. Moeller describes this world view as “acosmic”, a self-generating conceptual view of the world and how it was created (Moeller 40). Like the Dao, the root is invisible to the world but “is the source of nourishment for the plant” (Moeller 42), or the world which is visible. Moeller states how the Zhuangzi asserts the “futility of a philosophical search for an ultimate beginning” (Moeller 41) because of the fact that the world is a spontaneous and self-generating on-going process which had no precise beginning. Like the Dao did not exist before the world, the root does not exist before the plant, but is rather an integral part of the plant (Moeller 41). The Dao, like the root is to the plant, is fundamental to the world but remains a part. Contrary to Plato, the root does not transcend the plant’s physical existence, and is therefore not metaphysical. There is no supernatural force Finn 9 about that brought the plant into existence but instead was a part of the plant itself (Moeller 41). Daoist philosophy asserts that the natural balance of the world is cohesive with the balance of the Dao, such as the stability of the root determines the plant’s life. Comparative Epistemology Hellenistic and Doaist positions took on two very different knowledge theories, with the Hellenistic ratiocinative view employing descriptive and theoretical knowledge while the Daoists took a more prescriptive and practical approach. Hellenistic concepts attempt to attribute supernatural causes to the origin and creation of the world where Doaism believes the world to be self-creating and always changing. The two theories can be contrasted through the works of Plato and the Cook and Wheelwright parables in the book of Zhuangzi. Plato’s theory of the Divided Line illustrates the knowledge theory of Western thought during the Hellenistic Era. Western thinkers focused on supernatural reasons for the world, searching for an over reaching arche, or governing principle by which all things exist. Plato believed this arche to be the Realm of Forms, a supernatural realm which is perfect and eternal and completely independent. The empirical world is an imperfect copy of this realm and is dependent upon the supernatural realm for existence. These two realms are divided and exist separately from one another though the world is dependent upon the Realm of Forms. This supernatural way of thinking describes the general Hellenistic knowledge theory based on the concept of the supernatural being the ultimate cause of the world (Class lecture notes). The practical Doaist theory of knowledge can further be exemplified through the parables of the Cook and the Wheelwright. The parable of the Cook describes how if one divides things into smaller parts, one can easily accomplish tasks. This reflects the Chinese knowledge theory Finn 10 in that they view everything in detail and are more practical in their ways of thinking (Class handout). The Daoist philosophy is centered on the fact that the world is a practical selfgenerating process and is further shown through this parable. The parable of the Wheelwright, a story in which one man questions another reading books written by dead men, reflects upon the Doaist idea that the world is always changing and that nothing is permanent. The wheelwright asserts that he cannot teach what he knows to anyone other individual and that it would be pointless to look to the past for answers, as the world is ever changing (Class handout). Conclusion The Western hemisphere focused primarily on supernatural forces as an origin of the world, or an overarching being which governs all of existence. Plato set the stage for subsequent philosophers who took on his general theme through his “Allegory of the Cave” in describing his idea of metaphysical dualism and the idea that the Realm of Forms is the divine force which created the empirical world. These thoughts resonate in contemporary Western religious traditions, as in Christianity where God can be seen as the ultimate and perfect force which created the world in His image. Daoist perspectives concerning self-generating ideas are greatly differentiating from any form of metaphysical dualism, asserting that there is no divine or supernatural force which created the world (Moeller 40). They believe the world to be an ongoing process of which the Dao remains a part of continuously. These two different cultures adopted differences in knowledge theories as well, Hellenistic theories focusing on the supernatural causes of the world with Daoist theories taking a more practical approach, as seen through the Cook and Wheelwright parables in the book of Zhuangzi. Because these two cultures developed so independently from one another, they each took on very different methods of thinking and problem solving as well as different philosophical views (Ames 255). Finn 11 Works Cited Plato.“The Republic of Plato”. Introduction to World Philosophies, Elliot Deutsch. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 1997. Aquinas. “Summa Theologica in Basic Writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas”. Introduction to World Philosophies, Elliot Deutsch. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 1997. Augustine. “Evil as a Privation of Good”. Augustine of Hippo pdf file. Ames. “Alternative Rationalities”. Introduction to World Philosophies, Elliot Deutsch. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 1997. Moeller. “Daoism Explained From the Dream of the Butterfly to the Fishnet Allegory”. HansGeorg Moeller. Carus Publishing Company. 2004. Pdf file.