Plato written info on his ideas and the cave

advertisement

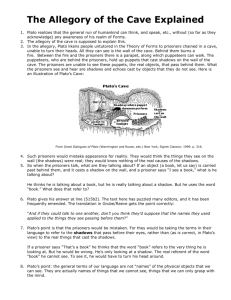

Plato’s Form of Good Plato believed that the Forms were interrelated, and arranged in a hierarchy. The highest Form is the Form of the Good, which is the ultimate principle. Like the Sun in the Allegory of the Cave, the Good illuminates the other Forms. We can see that Justice, for example, is an aspect of Goodness. And again, we know that we have never seen, with our senses, any examples of perfect goodness, but we have seen plenty of particular examples which approximate goodness, and we recognise them as ‘good’ when we see them because of the way in which they correspond to our innate notion of the Form of the Good. By Plato’s logic, real knowledge becomes, in the end, a knowledge of goodness; and this is why philosophers are in the best position to rule. The one who has philosophical knowledge of the Good is the one who is fit to rule. Plato’s belief in the fitness to rule of the philosopher is sometimes referred to as the ‘Philosopher King’ (even though Plato himself never used it). Plato developed his Theory of Forms to the point where he divided existence into two realms. There is the world of sense experience (the ‘empirical’ world), where nothing ever stays the same but is always in the process of change. Experience of it gives rise to opinions. There is also a world which is outside space and time, which is not perceived through the senses, and in which everything is permanent and perfect or Ideal - the realm of the Forms. The empirical world shows only shadows and poor copies of these Forms, and so is less real than the world of the Forms themselves, because the Forms are eternal and immutable (unchanging), the proper objects of knowledge. Plato's metaphor of the cave Plato's parable of the cave is a metaphor for ignorance and knowledge. Imagine, says Plato, a cave in which prisoners are chained in such a way that all they can see are shadows thrown on a wall in front of them. All they know of life are these shadows. They would think that these shadows were reality, having known nothing else. If one of them were freed, and allowed to emerge into the daylight, he would see things as they are, and realize how limited his vision was in the cave. He would be quite unwilling to return: And when he remembered his old habitation, and the wisdom of the den and his fellow-prisoners, do you not suppose that he would felicitate himself on the change, and pity them?...you must not wonder that those who attain to this beatific vision are unwilling to descend to human affairs; for their souls are ever hastening into the upper world where they desire to dwell. (Republic VII, 516) Yet to his fellow-prisoners, he would seem the fool, not they: And if there were a contest, and he had to compete in measuring the shadows with the prisoners who had never moved out of the den, while his sight was still weak, and before his eyes had become steady...would he not be ridiculous? Men would say of him that up he went and down he came without his eyes; and that it was better not even to think of ascending. (Ibid, 517)