1 Writers with Style . . . Select Strong, Specific Verbs

advertisement

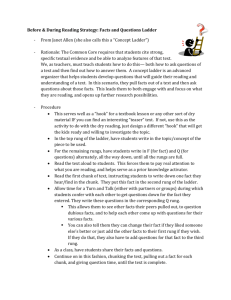

STYLE matters ****************************************************************************** 1 Writers with Style . . . Select Strong, Specific Verbs ****************************************************************************** What Are Strong Verbs? Typically, strong verbs possess a high degree of specificity and also describe a unique action. Most of the verbs that we use in casual conversation do not meet these two criteria. When we speak with friends, with family, even with shop owners and food servers, we tend to employ “catch all” verbs—nonspecific actions contingent on context. Take, for example, the verb “to get,” and consider how many actions it describes: I got an A on my History test. I got into the subway car. I got down when the baseball headed my way. I got up at six o’clock. I got over to the side of the road. = = = = = I earned an A on my History test. I boarded the subway car. I ducked when the baseball headed my way. I rose at six o’clock. I steered to the side of the road. Each one of those sentences relies on a slightly different use of the verb “to get,” illustrating the transportability of that general (and lifeless) verb. To complicate matters, we could easily take the same verb, even the same preposition following it, and “get” different results: I got the calculus lesson right away. I got into jazz in high school. I got down when my dog died. I got up for the big race. I got over the break up. = = = = = I grasped the calculus lesson right away. I discovered jazz in high school. I grieved when my dog died. I braced myself for the big race. I survived the break up. Here, one verb stands in for ten specific actions, which means that “to get” is highly transportable. Other verbs, such as “to be,” “to have,” “to see,” “to do,” “to make,” and “to go,” share that transportability, easily adapting to all sorts of different situations and contexts. They make impromptu speech and conversation easy, since we do not need to search for the precise verb. They also imply a particular attitude toward language, one that values ease over aesthetics, simplicity over style. They represent, in other words, the “lowest common denominator” of language use. In writing, these verbs do not carry much strength or exhibit much style. If they can shift around depending on context, then their degree of specificity must be low. To strengthen your writing, you first need strong verbs that describe highly specific actions, and that do not lend themselves to transportability. Observe some ways in which you can easily “ratchet up” the specificity in your verbs and render them more action-specific: F. Scott Fitzgerald does a good job of describing New York City during the ’20s. F. Scott Fitzgerald accurately describes New York City during the ’20s. The second chapter of Moby Dick is confusing. The second chapter of Moby Dick presents several perplexing questions. When Frost’s narrator says, “I took the [road] less traveled by,” he is being self-congratulatory. When Frost’s narrator declares, “I took the [road] less traveled by,” he adopts a self-congratulatory attitude. CALISTHENIC 1a Read the following sentences and ratchet up the specificity in the verbs. Weak, general verb Strong, specific verb 1. Can I have your dictionary? ___________ 2. I forgot to take back my library books. ___________ 3. Tim likes Coke more than Pepsi. ___________ 4. I am crazy about skeet shooting. ___________ 5. Arfana is really good in chemistry. ___________ 6. My little brother was like my shadow all day. ___________ 7. Professor Smith was a champion of my writing. ___________ 8. My parents frequently go to the opera. ___________ 9. The refrigerator made loud buzzing sounds. ___________ 10. Emily Dickinson was a writer of brief poems. ___________ The Active Voice Sentences written in the active voice can lend force and clarity to your writing. In an active-voice sentence, you place the actor (the doer, the subject) at the start of the sentence, followed by the action (the verb) that the actor performs. Example: Jane sat on the park bench. “Jane” = the actor, the subject; “sat” = the action, the verb Active sentences differ from “passive” sentences, where the actor/subject follows the verb. For example: “The bench was sat on by Jane.” Passive-voice sentences typically include weak verbs such as “was” and weak connecting words such as “by.” Concentrate on using the active voice effectively. Choose vivid, image-building, active verbs, and your writing will strengthen—guaranteed. Here are some active-voice examples from Annie Dillard’s essay “Living Like Weasels”: — He (subject, a weasel) sleeps (vivid, active verb) in his underground den. — He bites his prey at the neck. — Once, a man shot an eagle out of the sky. — He examined the eagle and found the dry skull. — The weasel swiveled and bit as instinct taught him, tooth to neck, and [he] nearly won. — I startled a weasel who startled me, and we exchanged a long glance. — The world dismantled and tumbled into that black hole of eyes. Often, in conjunction with active-verb constructions, expert writers such as Dillard effectively use “ing” verbs. This strategy offers relief from the repeated use of the subject/active-verb arrangement, while keeping the prose in the active voice: — In winter, brown-and-white steers (subject) stand (active verb) in the middle of Hollins Pond, merely dampening (“ing” verb) their hooves. — Outside, the weasel stalks rabbits, mice, muskrats, and birds, killing more bodies than he can eat warm, and often dragging the carcasses home. Your writing will engage more readers if you learn to diversify the style of your sentences. “Ing” verbs can help you stay in the active voice, while creating longer, more complex sentence constructions that your readers will appreciate. Study the difference between the following examples in passive and active voice. Also, note the detail provided by climbing the ladder of specificity. Example: Passive voice without specificity: A lot of beer was drunk by the young women in the sorority. Active voice with specificity: The Sigma Delta sisters guzzled three kegs of Bud. Example: Passive voice without specificity: People in this country are made to want lots of things by our capitalistic society. Active voice with specificity: American capitalism encourages the accumulation of material goods such as expensive automobiles, trendy clothing, and grandiose homes. CALISTHENIC 1b Convert the sentences below from passive to active voice: 1. The sandwiches were devoured by the football team. 2. The final code was keyed in by Hank. 3. Jerry was frightened by Julie’s pit bull. 4. Many tourists are stunned by the size of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. 5. The decision was made by the students to join the study abroad program in Germany. “To Be” Constructions Before turning in any writing, be sure to minimize “to be” constructions—is, am, are, was, were, be, and being. These words tend to sap the strength of college-level prose (and lower your grades). For practice, study the following examples from criticism on Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein: 1. As soon as the creature is given life, he is no longer pleasing to Victor. As soon as he stirs with life, the creature no longer pleases Victor. 2. To add to the creature’s understanding that he is unacceptable is his observation of the close-knit community of the cottagers. The creature’s sense of his unacceptability intensifies when he observes the close-knit community of the cottagers. 3. Some of the first concepts that Shelley’s monster begins to understand among the cottagers are the concepts of “father, brother, son, daughter, and mother” (103). His first inklings of understanding are that of acceptance and togetherness. He sees that the family seems to be happy because they are together. This is where the creature realizes his need for companionship. During his stay, he is also able to learn to read, and through that skill, he is able to increase his knowledge about the importance of human bonds. Among the cottagers, Shelley’s monster first understands the concepts of “father, brother, son, daughter, and mother” (103) and gradually learns about acceptance and togetherness. Witnessing the happy, unified family, the creature realizes his need for companionship. During his stay, he also teaches himself to read, which increases his knowledge about the importance of human bonds. CALISTHENIC 1c In the following excerpts, modify the “to be” verbs with more specific verbs. 1. J. Alfred Prufrock is very obsessed with the postponement of decisions. 2. One supporter of the theories of psychoanalysis was Sigmund Freud’s daughter Anna. 3. Samuel Beckett’s Endgame is an exploration into the threat of nihilism in modern society. 4. In Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens is making a point about the unequal class structures of nineteenth-century British society. 5. Jane Addams is considered one of the most effective social reformists in American history. Besides its passivity and inaction, “to be” also takes part in two other problematic and unstylish constructions, which you will want to avoid: “It is” / “there is” constructions When we write, “It is a beautiful day,” we don’t really need that initial “it is.” Sure, we will have to revise the sentence to avoid the fragment “a beautiful day,” but this challenge allows us to write a much more active and descriptive sentence: “Jillian awoke to brilliant sunshine and mockingbird chatter on her rooftop.” Constructions such as “it is,” “there is,” and “there are” represent empty language. Consider the following example, notice how easily we can delete “there are” at the beginning: There are several instances in which the narrator of Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” refers to the patriarch as a Nazi. The narrator of Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” often refers to the patriarch as a Nazi. CALISTHENIC 1d Rewrite the following sentences to overcome problematic “to be” phrasings: 1. There were hundreds of fans cheering in the stands. 2. It is common for elephant calves to weigh over 200 pounds at birth. 3. There was a dark cloud looming above the hill. 4. It is typically the case that American college students take out loans to cover the costs of school. 5. There is no way I am going to be persuaded to lend out my copy of Middlemarch. Progressives When you use a form of “to be” followed by a verb ending with “ing,” you deploy the progressive tense. Take, for example, the following sentences in the progressive: The author is saying that American culture was being overrun by crass opportunists. Sylvia Plath’s poem is suggesting that the father figure is a massive force, a colossus. The article is arguing for a more historically contextualized reading of Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado.” We tend to use this tense often in spoken English, and it dominates our conversational questions: “What are you doing tonight?” “What are you eating?” “How are feeling”? “When are you going to Sally’s party?” In writing, however, the necessity of the “to be” verb and the repetitive “ing” endings render the progressive tense both tiresome and unstylish. By avoiding the verb “to be” in all its forms, you simultaneously sidestep the progressive tense. CALISTHENIC 1e Strengthen the following sentences by removing the progressive tense: 1. That editorial is implying that the United Nations is lacking in direction and power. 2. The mayor is underestimating the intelligence of young voters in this city. 3. The construction industry is facing hard times. 4. That student who is repeatedly falling asleep in class is clearly playing on the professor’s nerves. 5. It is being suggested by the latest ad campaign for Gap jeans that pre-washed denim is gaining more appeal among teenage consumers. ****************************************************************************** 2 Writers with Style . . . Choose Strong, Specific Nouns ****************************************************************************** What Are Strong Nouns? Strong nouns refer to highly specific persons, places, and things. They offer, in other words, not generalizations and broad categories but focused and particular identifiers. Again, the kinds of nouns we commonly use in speech do not help us a great deal when writing stylish and informed prose for university classes. “Catch all” nouns such as “things,” “something,” “stuff,” and “junk” fail to add contour and specificity. They remain generic and, thus, unstylish. Other general nouns such as “people” similarly fail to add specificity to your writing. Consider this example: People tend to conform to religious principles. The problem lies in the general “people.” Not all people conform, so this statement will render your writing less persuasive and stylish. What happens, though, when we lend more specificity to those “people”: Most mid-nineteenth century New Englanders followed strict Protestant principles. Here, we build in two degrees of specificity in relation to our “people”—firmly rooting them in a particular time (“mid-nineteenth century”) and place (“New England”). Furthermore, we have specified the general term “religion.” Sharpening your nouns strengthens your persuasions, nuances otherwise vague declarations, and builds in style and flair. The same goes for “place.” We simply “climb the ladder of specificity,” with each rung representing a more focused version of a particular locale: first rung: second rung: third rung: fourth rung: town small town small town in the American South Carrollton, a small town and county seat in Northwest Georgia Note the degree of specificity on the fourth rung. Are all towns equal? Is a town in the outer Hebrides (a remote island chain off the northern coast of Scotland) the same as Carrollton, Georgia? Specificity lends credibility to your arguments. The same applies to larger cities: first rung: second rung: third rung: fourth rung: New York Manhattan Upper East Side “Museum Mile,” the stretch of the Upper East Side bordering Central Park and home to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Whitney, and the Guggenheim, among others. You can even imagine how the ladder of specificity could help you hone your descriptions of entire countries and continents: first rung: second rung: third rung: fourth rung: Europe Italy Northern Italy the wine country in the northwest Italian region of the Veneto In each case, higher rungs on the ladder of specificity lend greater stylistic focus. And what about “things”? Again, trust the ladder of specificity to help you build in particularity: first rung: second rung: third rung: fourth rung: equipment sports equipment fishing rod Orvis tip-flex graphite rod first rung: second rung: third rung: fourth rung: household items furniture chair leather La-Z-Boy recliner first rung: second rung: third rung: fourth rung: book novel Herman Melville novel limited-edition Moby Dick illustrated by Rockwell Kent We could extend our discussion to “time,” as we try studiously to avoid generalized chronological tags such as “back in the day,” “in early times,” “way back when,” and the like. (These are clichés—used-up phrases that carry little punch or meaning.) Instead, pinpoint your exact historical or chronological setting. Imagine, for example, you are composing an essay on one of William Shakespeare’s plays. Rather than the broadly defined “When Shakespeare was writing,” imagine one of the following: In Elizabethan England . . . In the second half of Queen Elizabeth’s reign . . . At the start of the seventeenth century, as England further advanced its imperial sway . . . The same holds true for an essay focused on an early American text. Instead of the bland and predictable “In colonial times,” consider one from the list below: Prior to the War of 1812 . . . In the early years of Jefferson’s presidency . . . In 1731, the year that Benjamin Franklin founded the first public library in America . . . Or what about criticism regarding the “contemporary American South”? If you sidestep the usual “The South, in recent years,” you might test out more specific options: During the first years of the twenty-first century, the states along the Gulf of Mexico . . . In the last two decades of the twentieth century, the American South . . . Since the Civil Rights era, states such as Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana . . . While many writers believe that leaving language broad and generic will afford their readers more space in which to “relate” and color the scene in their own ways, we suggest that only through specificity do readers understand general concepts. Give us the specifics, from which we will construct the general, if need be. In most university situations, however, specificity wins out. Climbing the ladder of specificity also compels you to stick to the physical and the precise. Forcing generalized language up the ladder—where every rung demands a new level of precision in terms of names, numbers, sensory detail, cinematic imagery, illustrative examples, and so on—will strengthen your prose and make it far more stylish. As an aid to memory, you might think about building in specificity and particularity by “Minding Your Ps & Qs.” We have borrowed this phrase from the early days of printing, when it was easy for manual typesetters to confuse the lower-case letters “p” and “q,” since these individual pieces of type looked very much alike when one or the other was turned upside down. Typesetters were constantly reminded to “mind”—or pay close attention to—their ps and qs, and this bit of advice can also help you overcome sweeping generalizations, sidestep needless repetitions, and steer clear of other weakening agents in your critical prose. Here is a helpful chart of ps and qs: Mind Your Ps & Qs Proper Nouns names of people, places and things; precise terms & Quantities amounts, numbers, calculations Physical Senses sight, sound, touch, taste, smell & Qualities shapes, sizes, colors, textures, materials Proofs evidence, examples, illustrations, proven data & Quotations noteworthy facts, expert testimony, citations of text Postulations theories, explanations, reasons & Questions who, what, where, when how, and why With continued practice climbing the ladder of specificity, your nouns—and by extension your writing—will achieve more nuance, more substance, and more style.