Low Risk Diversified Portfolio

advertisement

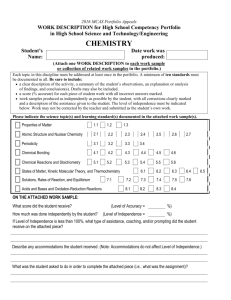

Low Risk Diversified Portfolio? How Do You KNOW? Michael Tove Ph.D, CEP, RFC May 2015 It’s so common, it’s cliché: “My portfolio is a diversified mix of higher risk investments (for growth) and lower risk investments (for safety).” Apart from the fact that there is ABSOLUTELY NO TRUTH to the notion that higher risk means better growth (see Riskadjusted Return), how do you KNOW your portfolio includes lower risk investments? Answer the following: “I know my investment portfolio is “Low Risk” because. . .” A) I ran all the correct mathematical calculations: Sharpe Ratio, Traynor Ratio, Capital Asset Pricing Model, Correlation Coefficients, etc. on every investment in the portfolio. B) My broker (or investment company) said it was. C) It was on the print-out by my investment company’s computer. D) I’m very diversified with many different funds across all sectors: domestic, international, large cap, small cap, etc. E) My portfolio includes a lot of bonds and cash. F) None of the above. The correct answer is “F” – None of the above. Let’s analyze. A. These mathematical formulae offer the only way to quantify (measure) relative risk between two investments. But they base those measures on what the investments did IN THE PAST, ignoring the wisdom of the cliché admonition “Past performance is no indicator of the future.” For years, there has been an assumption that markets were patterned and predictable but research by an increasing number of pre-eminent economists (George Akerloff, Robert Shiller, Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, Richard Thaler, etc.) have shown otherwise. The conclusion of these researchers is that markets are neither rational nor predictable any more than are the future results of tossing a coin or spinning a roulette wheel. One more thing. If you’ve never heard of those equations, don’t feel bad. Most investment advisors don’t know them either which means they don’t know what the risk of your portfolio really is (see response B below). B. Just because a broker or representative of an investment firm says something is “low risk” is utterly meaningless. How do THEY know? Chances are they didn’t even do the math mentioned in A (even if they knew how). They make those statements based on qualitative (non-factual) belief, fundamentally because that’s what they were taught… by people who were taught that by people who were... 1 C. Same with answer B. The computer spits out pie-charts based on variables programmed into the software. Those basic algorithms don’t change in real time for all the different circumstances in the lives of “real people” nor do they have the level of “Artificial Intelligence” necessary to make those adjustments. D. In theory, owning multiple funds from different parts of the world or different industry sectors diversifies a portfolio if those investments perform differently under specified economic conditions. However, since the mid-1990’s, the world has become so globally connected that markets respond in kind to what the others are doing, whether or not they’re related. Thus, if there is a market surge or plunge in China or Hong Kong, it affects how markets respond in Europe or the United States. In other words, in the modern era, old school theories of diversification do not actually deliver the results they’re theoretically supposed to. E. When bonds offer very low interest rates (such as typified the first decades of the 21 Century), they carry nearly as much risk as stocks. Even bond funds, from 2005 – 2015 did not perform consistently better than equity funds and following the financial collapse of 2007-08, lost value. F. In the end, NOTHING can accurately predict or guarantee the future including markets. And unfortunately, common theory that diversifying portfolios mitigates the negative volatility is yesterday’s news. Why? Because the stock market is fundamentally a secondary market place meaning previously issued shares of stock are bartered and sold by people who are speculating on the future performance of those assets, based on what they predict the future to be, short-term. But nobody can accurately predict the future. To be sure, there are financial experts who can build investment portfolios that are consistently successful, but they do not rely on the sort of rear-view mirror predictive (“technical”) analysis that is the basis of what dominates popular investing theory. The financial Gurus who do consistently beat the market are highly trained, skilled experts who know far more than the average lay person – including those who have done a “lot of self-study.” It’s like a suburban driver thinking because he’s driven a mid-sized sedan for 30 years makes him qualified to race in the Indianapolis 500. Efficient Markets Myth In 1955, Harry Markowitz, a graduate student in economics at the University of Chicago (working under the venerable economist Milton Friedman), wrote his dissertation describing strategies that diversified an investment portfolio for maximum optimization. In 1990, this theory, which eventually became known as Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. As Markowitz explains (see Levine 2011), “… asset classes move roughly in proportion to their historical betas,” he said. The beta value is a measure of how risky an asset is in relation to the overall stock market. The S&P 500, for example, has a beta 2 value of one. So a stock or mutual fund that has a beta value greater than one will lose more money when the market declines than a stock that has a beta value less than one.” The application of MPT in contemporary investing promotes the notion that diversifying a portfolio to include different classes of investments offers the chance to “beat the market” by having one investment that would go up to offset the losses of other when they went down. However, long before Markowitz, markets were described as unpredictable, being likened to a “Random Walk.” The notion of “Random Walk” stems from Jules Regnault (1863), Louis Bachelier (1900) and Karl Pearson (1905). It describes the path that an object takes as a result of completely random independent steps, each having nothing to do with the previous. In its earliest descriptions, the theory supposed the path of a person so drunk, he stumbles at complete random, starting from a light post. After a long series of random stumbles, he ends up back at the light pole, having made no net progress in any one direction. The widespread importance of the Random walk concept is not to be under-estimated. In contemporary science, it is a cornerstone of thought in such diverse fields as biology, chemistry (Brownian Motion), physics (Markov Chains), as well as economics, etc. In 1965, Eugene Fama, also at the University of Chicago, published his dissertation (1965a, 1965b) which concluded that future stock prices are unpredictable and follow a “Random Walk.” Essentially, Fama disagreed with Markowitz, saying that it’s impossible to beat the markets because market prices always incorporate all known and relevant information. In 1970, Fama updated his Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) to include three variations or “Forms.” The “Weak Form” states that Technical Analysis (looking for patterns in past performance) cannot successfully predict or be used to beat markets. However some forms of Fundamental Analysis (through economic study of corporate assets, liabilities, earnings, etc.) may offer an advantage to randomly selecting investments. The “Semi-Strong Form” states neither Technical nor Fundamental Analysis can produce reliable assurance of beating the market. Rather, only through the use of non-public information (insider information, etc.), can one out-perform a random market. The “Strong Form” states that nothing, whether legal or otherwise, can provide a long-term predictor of future market performance. The heart and soul of the EMH (and even MPT) is the notion that markets behave according to predictable patterns. The theories hold that the price of individual stocks will rise or fall in large part because of the underlying financial strength of the company. In fact, the very reason that shareholders are (or should be) interested in corporate decisions is because those decisions may 3 affect future stock prices. When value in the stock of a company increases, shareholders are benefitted by profits, either through profit-sharing payments called Dividends or by direct capital appreciation of the stock, or both. But what if markets were fundamentally not rational and unpredictable? What if one company who was doing poorly saw dramatic increases in stock value while another, stalwart company saw slipping stock prices? What if there was nothing anybody could do other than pick some random market investment and hope for the best? This was just the accusation made by a number of behavioral economists including Nobel Laureates George Akerloff, Daniel Kahneman and Robert Shiller (Kahneman, Knetsch & Thaler 1986; Dreman & Berry 1995; Shiller 2000, 2006, Dreman & Lufkin 2000, Akerloff and Shiller 2009). From the end of World War II through 1995, the general behavior of the markets was benign. With the single exception of “Black Monday” (the market crash of October 19, 1987), markets trended steadily upward with minimal volatility. Even throughout the first half of the 20th Century, including the 1929 market crash (“Black Monday” was larger) there was relatively little volatility over time horizons longer than three to five years. It is notable then, that these were the years upon which so much of investment theory was derived. But beginning January 1995, everything changed. Markets began growing as they never had before. For five years, U.S. Markets roared upward in the greatest Bull Market in history. Fortunes were made. Then the Dot-Com bubble burst. From March 2000 through October 2002, markets crashed, most notably the NASDAQ Composite Index losing nearly 78% of its value. But the losses were pervasive and cut across all sectors, affecting every imaginable market, even those that were seemingly uncorrelated to the events that precipitated the Dot-Com Bubble crash. By 2003, investors were feeling less vulnerable and the recovery began. It started slowly but picked up steam through 2007 when the “Great Recession” triggered by the financial misdealings of Citigroup, Lehman Brothers, Bear Sterns, Washington Mutual, AIG, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, struck. Over the next sixteen months, markets across the globe crashed more than 50%. The recovery that began in March 2009 has seen multiple single day swings far greater than anything that occurred between 1945 and 1987. By January 2013, markets had regained what was lost in each of the two crashes, but costing the average investor ten years of no net gain. Then over the next two years, the markets roared upward again. Investors seemingly forgetting the lessons of 1999/2000 and 2007/2008, pressed forward with exuberant zeal. Unfortunately, the overwhelming opinion among financial experts is that another significant correction will occur. 4 The real danger with the investing pop culture is the assumption that various portfolio manipulations (such as short-term trading) will out-perform the market as a whole. Obviously nobody can “beat the market” by passively participating in it. It’s analogous to trying to beat the race car you’re driving. So what’s wrong with trying to beat the market? The answer is nothing – as long as it works. This, in fact, is precisely what investment managers promote that they can do. Rather than simple buy a mutual fund, stick it in a drawer and forget it, individual investors as well as fund managers actively buy and sell, seeking to gain advantage by “buying low and selling high.” It makes a lot of sense in theory; too bad the results don’t match. According to DALBAR, Inc. (2015), a Boston-based independent financial services research firm, in 2014, the average equity mutual fund investor underperformed the S&P 500 by 8.19%. Where the S&P 500 returned 13.69%, the average investor gained just 5.50%. This surprising shortfall is actually consistent with a long-term pattern. DALBAR found that from 1995-2014 the S&P 500 returned 9.85% per year, whereas the average investor only gained 5.19%. Similarly, Morningstar’s director of funds research, Russel Kinnel (2014) reported that from 2003-2013 where the average Mutual Fund returned 7.3%, the average Mutual Fund investor gained just 4.8%. Both DALBAR and Kinnel attributed the disappointing result to imperfect investor timing. In other words, where everyone hoped to buy at the bottom and sell at the top, in “real life,” by being reactive, investors were consistently out of synch and inadvertently bought high and sold low (see also Marrion 2011). Michael Kitces (2012) suggested, as an alternate explanation for these findings, that the problem resulted from bad sequence of timing. As he points out, two investments with the same 10-year average return could have vastly different dollar-weighted returns (how much money is actually in the account) depending on whether a bull market occurred at the beginning or end of an investment cycle. In the end, identifying a “plausible” explanation why a portfolio under-performed expectations is like forgiving the burglar for the circumstances that led to his criminal behavior. Regardless of the reason, the conclusion to be drawn is that seeking to “beat the market” is likely to return less than simply trying to “match the market.” With volatility as high as it’s been since the mid1990’s, nobody can accurately “second guess” tomorrow’s market. The real problem is that today’s markets respond with investor knee-jerk reactions to random news events and not what the underlying corporations are actually doing. It’s precisely what prompted Yale professor of economics Robert Shiller to state that market behavior was based on “Irrational Exuberance” (Shiller 2000, 2005). 5 A second misrepresentation of fact has to do with portfolio diversification. Most investment advisors (and the computer models they rely on) spit out complex portfolios of different combinations of individual investments (stocks, bonds, mutual funds, etc.). But how does this compare with actual markets or single mutual funds? The answer may be surprising. The diversification theory suggests that a portfolio of different investments which move in different directions at different times such that the net (average) mitigates volatility, thereby reducing risk. Mathematically, risk is measured by volatility (the up and down swings that end up back at the same place), the most common approach being the standard deviation (average swings up and down from the average). In this regard, true portfolio performance is assessed by Risk-adjusted Return, not raw return (Sharpe 1964, see also Risk-adjusted Return). Essentially, lower volatility means less risk and that delivers higher risk-adjusted return. Thus diversifying a portfolio to mitigate volatility is thought to deliver a net better return. Unfortunately, there are two problems with the way most portfolios are diversified: 1. Over-diversification. Too often, portfolios look more like vast investment collections that include many different investments which fundamentally behave alike. This only adds complexity and potentially higher fees with no net benefit in performance. For example, an investor could purchase a collection of 50 to 100 individual stocks and manage that portfolio, perhaps with the assistance of a professional fund manager, buying and selling at supposedly opportune moments. Conversely, they could purchase a mutual fund. Mutual Funds are portfolio investments of typically 50 to 150 stocks that are managed by a professional fund manager. “But there’s more flexibility and customization to an individually managed portfolio.” a typical portfolio manager might argue. That is true and it would be advantageous if there were predictability in how different investments (based on different investment sectors). But that’s not the case and that’s the second mistake. 2. The assumption that different market sectors actually diversify each other is not supported by the data. Table 1 shows 20 years of the monthly performance of 6 major market indexes and their cumulative average from January 1, 1995 through December 31, 2014. What immediately jumps out is that the S&P 500, the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Russell 1000 were virtually identical and except for 1999-2003, so was the Russell 2000. The FTSE 100 (which represents international companies, predominantly European) underperformed everything but moved parallel with the others. The NASDAQ departed from the others from 1999 to 2002 and 2013 through 2014, but otherwise moved in a similar direction at the same time. More significantly, a “diversified portfolio” (by equal mix of all six) was virtually identical to the Dow, the S&P and Russell 1000. In other words, there was no net diversification among these six major market indexes. Conclusion: owning a lot of “different investments” may be little more than owning a collection different investments, not effective portfolio diversification. 6 S&P 500 DOW JONES NASDAQ 100 2000 2005 2010 2015 1 8 15 22 29 36 43 50 57 64 71 78 85 92 99 106 113 120 127 134 141 148 155 162 169 176 183 190 197 204 211 218 225 232 239 1995 FTSE 100 ALL COMBINED RUSSELL 2000 RUSSELL 1000 TABLE 1. Represents six major market indexes commonly thought to represent a broad and diversified cross-section of the investment markets. All graphs were adjusted to be on par with each other, starting at the same level. The graph covers the period from January 1, 1995 through December 31, 2014. KEY: Blue: S&P 500 - represents the best domestic companies in each of 10 defined market sectors. Red: Dow Jones Industrial Average - represents 30 of the largest (“Blue Chip”) Companies in the United States. Green: Nasdaq 100 - represents the top 100 “Over the Counter” stocks. Purple: FTSE 100 - represents the top 100 foreign, primarily European companies Yellow: Russell 2000 - represents an Index of Large Cap, Growth funds Orange: Russell 1000 - represents an Index of Small Cap, Growth Funds Black: All Combined - represents a “diversified” portfolio of equal weighting of the above six benchmark indexes. SUMMARY: The stock market is a place where would-be investors must accept risk in exchange for an expectation of return and the only reliable means of reducing risk is with Time IN the Market, not “Timing the market.” In other words, seeking to “beat the market” by actively trading and owning many different investments may look good in theory but over the long term, it does not work as well as many want to believe. In the end, the old school admonitions about market investing are once again proven correct: Invest for the long-term, buy and hold, don’t overdiversify, and don’t try to “beat the market.” A conservative, “old-school” strategy may not have “sizzle” but over time, it will win the race. 7 REFERENCES Akerloff, George A. and Robert J. Shiller. 2009. Animal Spirits. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. Bachelier, Louis. 1900. Theorie de la speculation. Annales Scientifiques de l’Ecole Normale Superieure Ser. 3(17):21–86. DALBAR (2015). Dalbar’s 21st Quantitative Analysis of Investment Behavior. Advisor Edition, Boston, MA David N. Dreman and Eric A. Lufkin 2000. Investor Overreaction: Evidence That Its Basis Is Psychological. The Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets. 1(1):61–75 http://www.signallake.com/innovation/DremanLufkin2000.pdf Dreman, David N. and Michael A. Berry. 1995. Overreaction, Underreaction, and the Low-P/E Effect. Financial Analysts Journal. July/August, 51(4). http://www.cfapubs.org/doi/abs/10.2469/faj.v51.n4.1917 Fama, Eugene. F. 1965a. Random walks in stock market prices. Financial Analysts Journal 21(5), 55–59. Reprinted 1995 as Random Walks in Stock Market Prices. Financial Analysts Journal 51(1), 75–80. Fama, Eugene F. 1965b. The behavior of stock-market prices. Journal of Business 38(1):34–105. Kahneman, Daniel, Jack L. Knetsch and Richard H. Thaler. 1986. Fairness and the assumptions of economics. Journal of Business vol. 59, no.4, pt. 2, s285-s300. http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/Richard.Thaler/research/pdf/Fairness%20and%20the%20Assum ptions%20of%20Economics.pdf Kinnel, Russel. 2014. Mind the gap 2014. Morningstar Fund Investor, Online report, February 27. http://www.morningstar.com/advisor/t/88015528/mind-the-gap-2014.htm Kitces, Michael, Oct 3, 2012. Does The DALBAR Study Grossly Overstate The Behavior Gap? Nerd’s Eye View. https://www.kitces.com/blog/does-the-dalbar-study-grossly-overstate-the-behavior-gap-guestpost/ Levine, Alan. 2011. Harry Markowitz – Father of Modern Portfolio Theory – Still Diversified. The Finance Professional’s Post (A Publication of the New York Society of Security Analysts), 8 Dec 28. http://post.nyssa.org/nyssa-news/2011/12/harry-markowitz-father-of-modern-portfoliotheory-still-diversified.html Marrion, Jack. 2011. Buy High, Sell Low, Lose Big. Advantage Compendium, Ltd., St. Louis, MO. Pearson, Karl. 1905. The problem of the random walk. Nature 72 (1865):294. Regnault, Jules 1863. Calcul des Chances et Philosophie de la Bourse. Mallet-Bachelier et Castel, Paris. Sharpe, William F. 1964. Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. The Journal of Finance 19(3):425–442. Shiller, Robert J. 2000. Irrational Exuberance. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. Shiller, Robert J. 2005. Irrational Exuberance: Second Edition. Princeton University Press, NJ 9