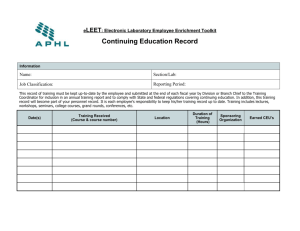

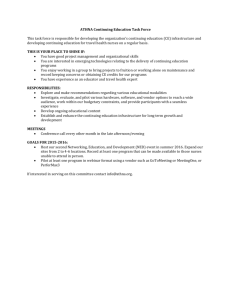

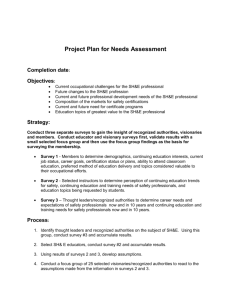

Towards more effective continuing education and training for

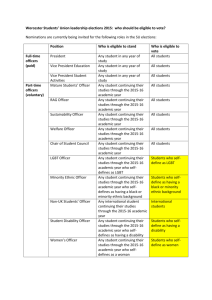

advertisement