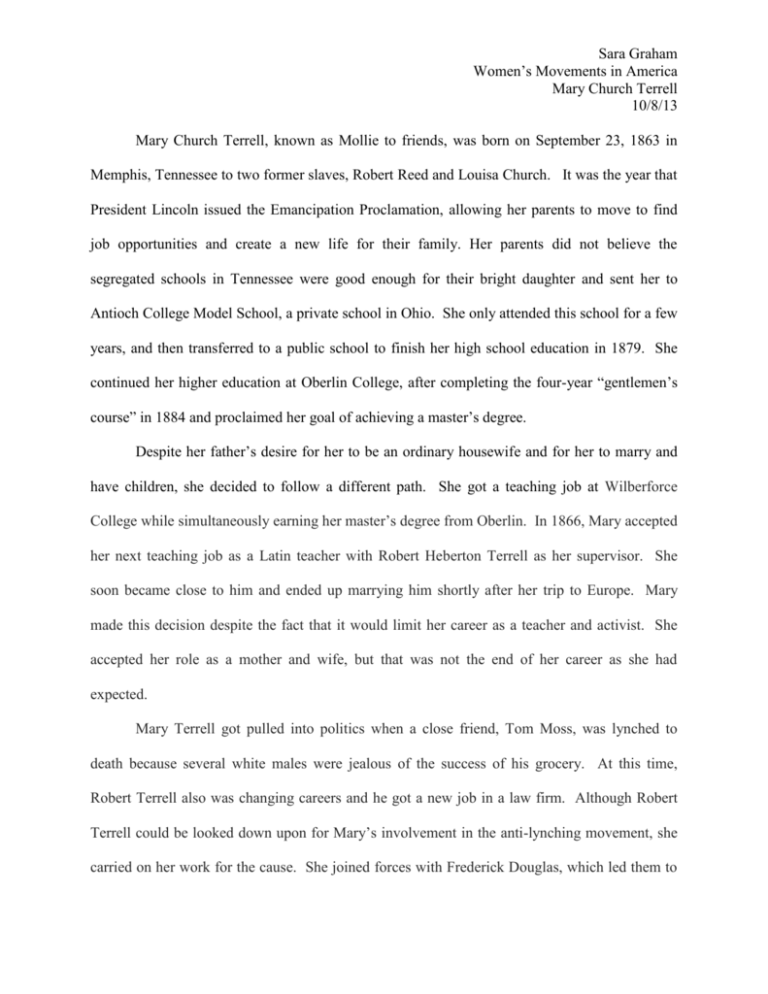

Mary Church Terrell

advertisement

Sara Graham Women’s Movements in America Mary Church Terrell 10/8/13 Mary Church Terrell, known as Mollie to friends, was born on September 23, 1863 in Memphis, Tennessee to two former slaves, Robert Reed and Louisa Church. It was the year that President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, allowing her parents to move to find job opportunities and create a new life for their family. Her parents did not believe the segregated schools in Tennessee were good enough for their bright daughter and sent her to Antioch College Model School, a private school in Ohio. She only attended this school for a few years, and then transferred to a public school to finish her high school education in 1879. She continued her higher education at Oberlin College, after completing the four-year “gentlemen’s course” in 1884 and proclaimed her goal of achieving a master’s degree. Despite her father’s desire for her to be an ordinary housewife and for her to marry and have children, she decided to follow a different path. She got a teaching job at Wilberforce College while simultaneously earning her master’s degree from Oberlin. In 1866, Mary accepted her next teaching job as a Latin teacher with Robert Heberton Terrell as her supervisor. She soon became close to him and ended up marrying him shortly after her trip to Europe. Mary made this decision despite the fact that it would limit her career as a teacher and activist. She accepted her role as a mother and wife, but that was not the end of her career as she had expected. Mary Terrell got pulled into politics when a close friend, Tom Moss, was lynched to death because several white males were jealous of the success of his grocery. At this time, Robert Terrell also was changing careers and he got a new job in a law firm. Although Robert Terrell could be looked down upon for Mary’s involvement in the anti-lynching movement, she carried on her work for the cause. She joined forces with Frederick Douglas, which led them to the White House. They approached President Benjamin Harrison and asked him to speak out for the racial injustice being shown towards blacks. Unfortunately, he never supported the black people and their rights to live without fear of being lynched for anything at anytime by white men in power. The reason he ignored her was because saying no to her request could not harm him. She was a woman and had no right to vote, which caused Mary to join women’s suffrage and racial equality movements into one objective. In 1892, Mary became the leader of a local Washington, DC club called the Colored Women's League. This club soon joined with other clubs to create the National Association of Colored Women, which she then was elected president for three terms. She was named honorary president for life, and this signified her importance to the movement. Her renowned motto was “lift as we climb.” This association did much in the way of social reforms; they created day care centers for black workingwomen’s children, campaigned for women’s right to vote, worked for racial equality, and enhanced working conditions for black women. She had said in response to some mean comments, "I resolved that so far as this descendant of slaves was concerned, she would show those white girls and boys whose forefathers had always been free that she was their equal in every respect. . . . I felt I must hold high the banner of my race." This view and position really jump-started her career as a speaker and figure of the movements she supported. As the 19th century came to a close, Mary was recruited by the Slayton Lyceum Bureau to be a professional lecturer because she had become such a popular national symbol. Even though she had already taken part of a lot of different associations, clubs, and causes, she still joined yet another group. She became a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, NAACP, which she stayed until she died on July 24, 1954 in Annapolis, Maryland. The NAACP did fought to uphold the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. The next major event to occur in her life was the publishing of her autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World. All of her work led her to great success; she was even there to witness women achieve the right to vote, which she then took advantage of as she became a member of the Republican Party. She had even been named one of the 100 most successful graduates of Oberlin College. In 1949, Mary became chairperson of the Coordinating Committee for the Enforcement of District of Columbia Anti-Discrimination Laws. Additionally, she was a part of a case that went to the Supreme Court because she was refused service at a public restaurant. The case was won in 1953, just before her death. Furthermore, the Brown V. Board of Education ruling had just been decided months before her death. Mary had a hand in everything she could and got to see almost all of those causes succeed in some way during her lifetime. Bibliography 1. "Mary Church Terrell." Contemporary Black Biography. Vol. 9. Detroit: Gale, 1995. Biography In Context. Web. 9 Oct. 2013. 2. "Mary Church Terrell." Encyclopedia of World Biography. Vol. 23. Detroit: Gale, 2003. Biography In Context. Web. 9 Oct. 2013. 3. Richardson, Mattie Udora. "No more secrets, no more lies: African American history and Compulsory Heterosexuality." Journal of Women's History 15.3 (2003): 63+. Biography In Context. Web. 9 Oct. 2013. 4. "100 Years of History." NAACP | National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. NAACP, n.d. Web. 09 Oct. 2013. <http://www.naacp.org/>.