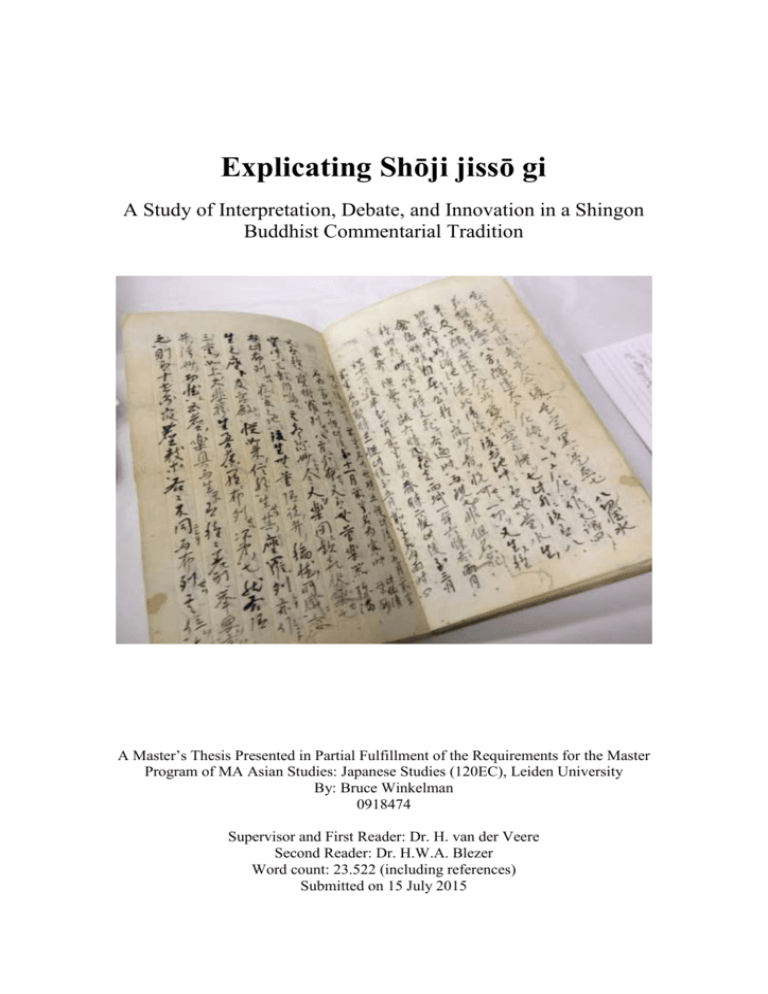

mathesis_final_winkelman_0918474 (120EC Japans)

advertisement