Delvaux - CLAS Users

advertisement

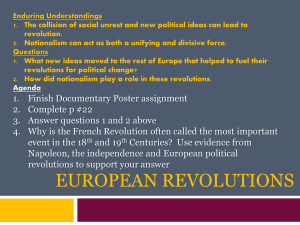

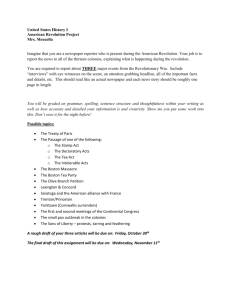

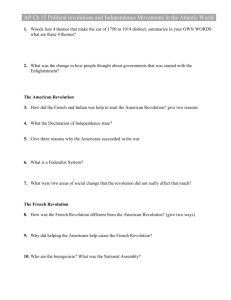

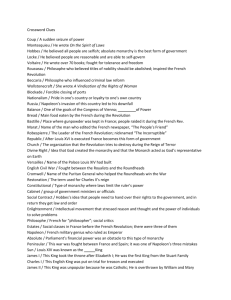

EUH5934: Atlantic History and Beyond Lecture Assignment (revised 4/23) Delvaux 1 of 3 Age of Revolutions – Lecture Outline WOH4234: Atlantic Exchanges from Columbus to NATO This lecture could feasibly be adapted to an hour-long course or a two-hour lecture period, depending upon the level of detail desired. However, in a course such as WOH4234, it would work best as a lecture delivered over two periods. For example, on Monday, the American and French Revolutions would be considered (slides 1-11). On Wednesday, the Spanish-American Revolutions would be considered (slides 11-31). These lectures would be joined by the repetition of slide 11, as well as the repetition of learning objectives (slide 2) in the discussion slide (slide 31). Friday period would be dedicated to discussing the learning objectives (slides 2 and 31) and key terms (slide 32). During discussion, students would also develop a list of key events, in conjunction with the instructor. Images behind the text are offered only so that students may more readily recognize them upon later encounters. If time allows, images would be discussed during the lecture. (Also, I would ideally incorporate a sound clip of “La Marseillaise” to accompany the slide “Aux armes, citoyens,” which would break up the monotony of the lecturer’s voice.) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. The Age of Revolutions in the Atlantic World (Title Slide) image: Francisco de Goya (1746-1828), El Tres de Mayo de 1808 (1814). Napoleonic soldiers execute Spanish resistance fighters in Madrid, 3 May 1808. Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain.1 Learning Objectives image: attributed to Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), “Join, or Die,” The Pennsylvania Gazette, 9 May 1754. An Age of Revolutions: What is the Age of Revolutions? 1. Define “Age of Revolutions.” A worldwide series of revolutions, 1750-1850 2. Orient students to key events. American, French, Haitian, Napoleonic, Latin-American, 1848 3. Emphasize that these are revolutions of the Atlantic World. Revolutions also occurred elsewhere. An Age of Revolutions: Why an Age of Revolutions? 1. The revolutions that occurred throughout the Atlantic world, 1750-1850, were not just coincidental, but shared common themes, causes and effects. 2. Thinking about this era as an Age of Revolutions helps historians explore what connects these revolutions, as well as what makes each revolution a unique historical event. Mixing the Powder image: Claude Joseph Vernet (1714-1789), La Rochelle Harbor in 1762 (1762). Musée de la Marine, Paris. 1. Empires and Colonies. European Empires exploit colonies for resources, depend upon colonies for economic prosperity; colonies depend upon metropoles for economic infrastructures, protection. 2. Eurocentrism. Colonists identify with European metropoles; metropoles use colonies to achieve political ends in Europe. 3. An Integrated Atlantic. New economic system, new merchant class, new aristocracies based on resource exploitation. 4. New Communities, New Identities. New communities within the integrated Atlantic foster formation of creole identities. Priming the Pan – The First World War? image: Benjamin West (1738-1820), Death of General Wolfe (1770). British General James Wolfe dies on the Plains of Abraham where the British won the Battle of Quebec, 13 September 1759, securing control of French Canada. The French commander, the General Marquis de Montcalm, also died in the fighting. National Gallery of Canada, Ottowa, Ontario. 1. A series of wars in which metropolitan politics increasingly disrupts the Atlantic world, metropoles compete for colonies, colonies suffer and are expected to fight. Sparks of Conflict 1. Cost of wars increase as metropoles defend colonies and colonial infrastructures. 2. Metropoles revise colonial policies to ensure continued cash flow, centralize administrations, increase taxation. 3. Colonists form networks of support during conflicts, forced to evolve a measure of self-sufficiency. 4. Metropoles trade colonies during peace process: emphasizes that colonies are in some ways independent units, begins dissolving sense of community with metropole. (Contrast with self-rule idea of virtual representation.) The Shot Heard Round the World – The American Revolution image: Emanuel Leutze (1816-1868), Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), Washington attacks Hessians at Trenton, All images are in the public domain and available from Wikipedia, accessed 22 April 2012; available from http://en.wikipedia.org/. 1 EUH5934: Atlantic History and Beyond Lecture Assignment (revised 4/23) Delvaux 2 of 3 night of 26–27 December 1776. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. 1. Colonists identify selves as having borne the brunt of fighting during the Seven Years’ War, begin questioning parliamentary legislation for defense and taxation and more stringent enforcement of old tax laws that stem from the Seven Years’ War. 2. New ideas of community develop, primarily based at the level of the individual colony, although some interdependence for defense and economic reasons is acknowledged; notably, the colonies which declare independence only include the colonies which had been British during the Seven Years’ War. 3. Warfare is uniquely American, guerilla fighting and piracy help colonists overcome line tactics of European warfare. 4. France capitalizes upon the disruption of Britain’s empire, supports the colonists and helps guarantee successful independence. (Britain will do likewise to prevent France from exploiting Spanish colonies during occupation of Spain.) 9. Aux armes, citoyens! – The French Revolution image: Jean Duplessis-Bertaux (1747-1819), Prise du palais des Tuileries (1793). Revolutionaries attack the Tuileries Palace, massacre the Swiss Guard, and seize the royal family, 10 August 1792. Palace of Versailles, France. 1. America established as a colony without a monarchy; intellectual currents spread back to Europe. 2. Metropolitan citizens begin considering prospect of a metropole without a monarchy, based on the same ideals. 3. French Revolution begins in 1789 rallying around principles of liberty, equality, and patriotism. 4. Practically speaking, these ideas require a constitutional democracy; conscription required to suppress royalists and foreign intervention, but also helps create a new national sense of identity; new patriotism appropriates power and wealth of national and international organizations from the ancien régime, namely the divine monarch and the Catholic Church. 10. A Whiff of Grapeshot – The Napoleonic Empire image (left): Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), Napoleon on his Imperial Throne (1806). Napoleon received the crown from Pope Pius VII and crowned himself Emperor of the French, 2 December 1804. Musée de l'Armée, Les Invalides, Paris. image (right): Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801). Napoleon crosses the Great St. Bernard Pass into Italy to regain territory seized by the Austrians, May 1800. Musée national du château de Malmaison, Rueil-Malmaison, France. 1. Allies join to suppress Revolution, preserve monarchy. Allows Revolutionary hero Napoleon consolidates power. 2. Napoleon institutes reforms, initially based on Republican ideals, and begins a counter-offensive against monarchies that had tried to suppress the Revolution. 3. Republican innovation of conscription provides Napoleon with the armies to conquer much of Europe, eventually extending from Portugal to Moscow; lasting impacts include the overthrow of the Holy Roman Empire and the displacement or dissolution of monarchies and aristocracies; however, especially as Napoleon becomes more secure in his power, he begins installing family members as replacement monarchies, especially in Italy and Spain. 11. Combustion image: January Suchodolski (1797–1875), Battle at San Domingo (1845). No further information given. 1. Liberté, Égalité, Slavery? Haitian Revolution begins as an independence movement, but a slave revolt ensues based on Revolutionary ideas, using Revolutionary language; Napoleon unable to commit sufficient troops to crush the revolt; becomes a warning to other slave societies in the Atlantic World, either don’t revolt or control the slaves (and indigenes). 2. Trafalgar. An outnumbered Nelson defeats combined French and Spanish fleets, leaving Britain with almost sole control of the Atlantic. 3. Napoleon attempts to break British power by mandating an embargo on British goods throughout Continental Europe, further isolating Europe from the colonies. 4. Napoleon allies with Spain to force Portugal to join Continental System; alliance allows Napoleon to saturate the Peninsula with French troops; pro-Republican Spaniards encourage Napoleon to invade; forces the Spanish Bourbon monarchy into the abdications of Bayonne; installs his brother, sparking the Peninsular War and a crisis of loyalties in the colonies. 5. Brazil, refuge for monarchy (1808); elevated to sovereign status and united with Portugal (1815); refuses to return to colonial status and declares independence under regent monarch (1822). 12-29. Spanish-American revolutions image: From “Spanish American wars of independence,” Wikipedia, accessed 22 April 2012; available from http://en.wikipedia.org/. 1. European conflicts disturb power relations between metropoles and colonies. EUH5934: Atlantic History and Beyond Lecture Assignment (revised 4/23) Delvaux 3 of 3 2. Ideas of self-rule reinforced by experience of self-sufficiency in absence of metropolitan governance. 3. Ambiguous or conflicting loyalties to juntas or monarchy makes independence the only option with clear implications. 4. Military leaders consolidate political power. 5. Impacts of intervention from other Atlantic powers: Britain tries to prevent France from benefiting from Spanish colonies; United States tries to construct new centers of power. 30. Repercussions image: Howard Chandler Christy (1873–1952), Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States (1940). Scene depicting Independence Hall, Philadelphia, 17 September 1787. East Stairway, House of Representatives Wing, United States Capitol. 1. Libertadores – South American military leaders, using Revolutionary language and tactics, establish new states during the disestablishment of the Bourbon monarchy. 2. Slave trade disrupted, New England industrializes, America becomes an independent source of merchant sailors, new American trade networks established that transcend old imperial boundaries. 3. Continental System forces new demands for self-sufficiency on Britain, beginning a transition to industrialization; consolidation and urbanization of political power joins with technological advances to begin the Industrial Revolution. 4. Republican and Revolutionary ideas respond to industrialization; basis of Communism, Revolution of 1848 31. Discussion image: Francisco de Goya (1746-1828), The Second of May 1808 or The Charge of the Mamelukes (1814), companion piece to El Tres de Mayo de 1808. Malmelukes, the French Imperial Guard, charge into a crowd of rioting citizens in Madrid, 2 May 1808. Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain. 1. Answer student questions or discuss learning objectives as time allows. 32. Key Terms.