File - PROFESSIONAL teaching profile

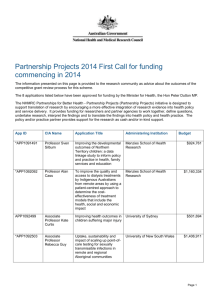

advertisement

Indigenous Australian Cultures The Dreaming The centre of Indigenous Australians’ cosmology and philosophy is, what is referred to as, the Dreaming and its link between humans, land and everything on the land (Hume, 2002, p. 24). The concept of the dreaming states there was a period of creation where creator beings performed deeds. As theses deeds were performed they moulded the landscape and created the customs followed by Aboriginal people. The beings of the Dreaming are the spiritual Ancestors of the Aboriginal People. These Ancestors are seen as animals, birds, plants, atmospheric and cosmological phenomena and even disease (Clarke, 2003, p. 16). The title, the Dreaming, is an English translation, it is known in a variety of language forms. For example, it is referred to as djuguba throughout the Great Victorian Desert, duma, in the Rawlinson range, djumanggani in the Balgo area and ngarunggani in the eastern Kimberley (Hume, 2002, p. 28). The Dreaming provides Indigenous Australians with the answers to areas of life such as origin, meaning, purpose, and destiny of life, as it relates to the past, present and future (Clark, 2003, p. 16) and it connects the Aboriginal people with the land, events and geographically together (Hume, 2002, p. 27). For example, the Ngarrindjeri people believe the Murray River was formed when Ngurunderi, a male ancestor, chased a large Murray codfish down a narrow creek, forcing the banks to widen (Clarke, 2003, p. 17). Kinship The kinship system is very important to Indigenous Australians, social life is centred on it, it provides cannels for the sharing of meaning and experience as well as identification and it is through this vast network that can help one understand the Aboriginal people, mainly through the naming process (MacDonald, 1998, p. 303). The first level of kinship is the moiety. You either inherent your mother’s or father’s moiety. Aboriginal people cannot marry someone of the same moiety and those with the same moiety are your first level of care (The University of Sydney, 2014, August 11a). The second level of kinship is totems. Every Indigenous Australian is given a totem that represents their nation, clan and family group (The University of Sydney, 2014, August 11b). Member from the same totem believe to be united decedents from a common ancestor (Bani, 2004, p. 151). The third level of kinship is skin name. An Indigenous Australian’s skin name identifies their blood line. Husbands, wives and 1 Kyle Palmer, 11540705 children do not have the same skin name. Those with the same skin name are consider to be your brothers and sisters (The University of Sydney, 2014, August 11c). These levels create connections between the Aboriginal people and the environment. For the Wiradjuri people, kinship is a key social expression (MacDonald, 1998, p. 300). There is diversity between different nations as the Yanyuwa and Garrwa system of kinship is characterised by four terminological lines (Bradley, 2006, p. 161). Economic Organisation The trading of goods and ideas was a feature of Indigenous Australian life. Through trade, other nations could get items that were not available in their own area. Trading was sometimes done at special places such as Kopperamanna on the Copper Creek in eastern South Australia (Gibbs, 1996, pp. 47-8). Knowledge of the environment and skill in maintaining its resources enabled Aboriginal people to survive and have enough to trade. Aboriginal people are resourceful, as they are able to find enough food for a balanced diet but also have plenty of time for leisure (Gibbs, 1996, p. 38). Some techniques the Aboriginal people used to manage the land, animal habitats and food sources was burning the land, to allow new growth, control their population and the creation of forests next to grass lands (Australian National University, 2011, February 27). For example, the Yarralin people would burn the grass in the wet season, later they would be able to hunt fat kangaroos and wallabies. Effective management of the land involved knowing when to hunt and gather a species and when to leave it alone (Rose, 1998, p. 247). By following these resource management techniques it meant they followed the law set by the dreaming (Australian National University, 2011, February 27). For the Yanyuwa and Garrwa people the economic ties of the cycad palm creates a long history of intermarriage, intergroup alignment (Bradely, 2006, pp. 162-3). Men and women have different roles within the economic organisation. For example, the Eora women would fish with a hook and line in a canoe and the men would use a spear off the rocks (Bennett, 2007, p. 88). Link The principles of Aboriginal people’s lives (kinship and economic organisation) were determined in the Dreaming. To be ignorant of one’s origin, of the meaning of one’s life and of one’s place in the cosmos, according to the Indigenous Australians is to be both rootless and witless (Rose, 1998, p. 247). Therefore these three areas are linked. 2 Kyle Palmer, 11540705 Reference List Australian National University (2011, February 27). Bill Gammage discusses ‘The Biggest Estate on Earth [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SkoYDIULKY Bani, E. (2004). Torres News, the voice of the Islands: what is a totem? In R, Davis (Ed.), Woven histories, dancing lives: Torres Strait Islander identity, culture and history (p. 151). Acton, A.C.T: AIATSIS. Bradley, J. (2006). The Social, economic and historical construction of cyad palms among the Yanyuwa. In I. J. McNiven, B. Barker & B. David (Eds.), The Social Archaeology of Australian Indigenous Societies (pp. 161-81). Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press. Clarke, P. (2003). Where the Ancestors Walked: Australian as an Aboriginal Landscape. Retrieved from the EBook Library. Gibbs, R. M. (1996). The Aborigines (4th ed.). South Melbourne: Addison Wesley Longman Australia Pty Limited. Hume, L. (2002). Ancestral Power: The dreaming, consciousness, and Aboriginal Australians. Carlton South: Melbourne University Press. MacDonald, G. (1998). Continuities of Wiradjuri tradition. In W.H. Edwards (Ed.), Traditional Aboriginal society (2nd ed.) (pp. 297-312). South Melbourne. Macmillan. Rose, D.B. (1998). Consciousness and responsibility in an Australian Aboriginal religion. In W.H. Edwards (Ed.), Traditional Aboriginal society (2nd ed.) (pp. 239-251). South Melbourne: MacMillan. The University of Sydney. (2014, August 11)a. Aboriginal Kinship Presentation: Moiety [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lvTYMJcvfU4 The University of Sydney. (2014, August 11)b. Aboriginal Kinship Presentation: Totems [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpHG9V2qJiE The University of Sydney. (2014, August 11)c. Aboriginal Kinship Presentation: Skin names [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ynQEtTfQjQc 3 Kyle Palmer, 11540705