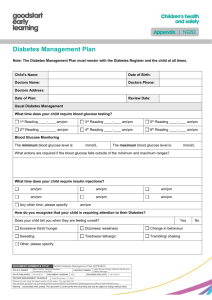

Diabetes_acc

advertisement