Louis Sullivan - Sat Priya School Architecture & Design

advertisement

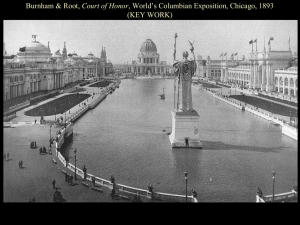

Louis Sullivan Louis Henri Sullivan (September 3, 1856 – April 14, 1924) was an American architect, and has been called the "father of skyscrapers” and "father of modernism". He is considered by many as the creator of the modern skyscraper, was an influential architect and critic of theChicago School, was a mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright, and an inspiration to the Chicago group of architects who have come to be known as the Prairie School. Along with Henry Hobson Richardson and Frank Lloyd Wright, Sullivan is one of "the recognized trinity of American architecture" Biography Louis Sullivan[4] was born to an Irish-born father and a Swiss-born mother, both of whom had immigrated to the United States in the late 1840s. He grew up living with his grandmother in South Reading (now Wakefield), Massachusetts. Louis spent most of his childhood learning about nature while on his grandparent’s farm. In the later years of his primary education, his experiences varied quite a bit. He would spend a lot of time by himself wandering around Boston. He explored every street looking at the surrounding buildings. This was around the time when he developed his fascination with buildings and he decided he would one day become a structural engineer/architect. While attending high school Sullivan met Moses Woolson, whose teachings made a lasting impression on him, and nurtured him until his death. After graduating from high school, Sullivan studied architecture briefly at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Learning that he could both graduate from high school a year early and pass up the first two years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by passing a series of examinations, Sullivan entered MIT at the age of sixteen. After one year of study, he moved to Philadelphia and talked himself into a job with architect Frank Furness. Later career and decline In 1890 Sullivan was one of the ten architects, five from the Eastern U.S. and five from the Western U.S., chosen to build a major structure for the "White City", the World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893. Sullivan's massive Transportation Building and huge arched "Golden Door" stood out as the only forward-looking design in a sea of Beaux-Artshistorical copies, and the only multicolored facade in the White City. Sullivan and fair director Daniel Burnham were vocal about their displeasure with each other. Sullivan was later (1922) to claim that the fair set the course of American architecture back "for half a century from its date, if not longer."[6] His was the only building to receive extensive recognition outside America, receiving three medals from the Union Centrale des Arts Decoratifs the following year. By both temperament and connections, Adler had always been the one who brought in new business to the partnership, and after the rupture Sullivan received few large commissions after the Carson Pirie Scott Department Store. He went into a twenty-year-long financial and emotional decline, beset by a shortage of commissions, chronic financial problems and alcoholism. Selected projects Buildings 1887–1895 by Adler & Sullivan: Martin Ryerson Tomb, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago (1887) Auditorium Building, Chicago (1889) Carrie Eliza Getty Tomb, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago (1890) Wainwright Building, St. Louis (1890) Charlotte Dickson Wainwright Tomb, Bellefontaine Cemetery, St. Louis (1892) which is lised on the National Register of Historic Places [11][12][13][14] is considered a major American architectural triumph,[15] a model for ecclesiastical architecture,[16] a "masterpiece",[17] and has been called "the Taj Mahal of St. Louis." Interestingly, the family name appears nowhere on the tomb.[18] Union Trust Building (now 705 Olive), St. Louis (1893; street-level ornament heavily altered 1924) Guaranty Building (formerly Prudential Building), Buffalo (1894) Buildings 1887–1895 by Louis Sullivan, with Dankmar Adler until 1895. Springer Block (later Bay State Building and Burnham Building) and Kranz Buildings, Chicago (1885–1887) The Auditorium Building, Auditorium Hotel and Auditorium Theater (now Roosevelt University), Chicago (1886–1890) Selz, Schwab & Company Factory, Chicago (1886–1887) Commercial Loft for Wirt Dexter, Chicago (1887) Standard Club of Chicago, Chicago (1887–1888) Hebrew Manual Training School, Chicago (1889–1890) James H. Walker Warehouse & Company Store, Chicago (1886–1889) Warehouse for E. W. Blatchford, Chicago (1889) Kehilath Anshe Ma'ariv Synagogue (also known as the K.A.M. Temple, later known as the Pilgrim Baptist Church), Chicago (1890–1891) James Charnley House (also known as the Charnley–Persky House Museum Foundation and the National Headquarters of the Society of Architectural Historians), Chicago (1891– 1892) Albert Sullivan Residence, Chicago (1891–1892) Transportation Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago (1891–1893) McVicker's Theater, second remodeling, Chicago (1890–1891) Bayard Building, (now Bayard-Condict Building), 65–69 Bleecker Street, New York City (1898). Sullivan's only building in New York, with a glazed terra cotta curtain wall expressing the steel structure behind it. Commercial Loft of Gage Brothers & Company, Chicago (1898–1900) Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church and Rectory, Chicago (1900–1903) Carson Pirie Scott store, (originally known as the Schlesinger & Mayer Store, now known as "Sullivan Center") Chicago (1899–1904) Virginia Hall of Tusculum College, Greeneville, Tennessee, 1901 Van Allen Building, Clinton, Iowa (1914) The banks A portion of the National Farmer's Bank's west face, Owatonna, Minnesota (1908) National Farmer's Bank, Owatonna, Minnesota (1908) Peoples Savings Bank, Cedar Rapids, Iowa (1912) Henry Adams Building, Algona, Iowa (1913) Merchants' National Bank, Grinnell, Iowa (1914) Home Building Association Company, Newark, Ohio (1914) Purdue State Bank, West Lafayette, Indiana (1914) People's Federal Savings and Loan Association, Sidney, Ohio (1918) Farmers and Merchants Bank, Columbus, Wisconsin (1919) First National Bank, Manistique, Michigan (1922–1924) A remodeling of an existing bank building. Lost Sullivans Grand Opera House, Chicago. 1880. Demolished 1927. Pueblo Opera House, Pueblo, Colorado. 1890. Destroyed by fire 1922. New Orleans Union Station, 1892. Demolished 1954. Dooly Block, Salt Lake City, Utah. 1891. Demolished 1965. Chicago Stock Exchange Building. Adler & Sullivan. 1893. Demolished 1972. The Trading room from the Stock Exchange was removed intact prior to the building's demolition and was subsequently restored in the Art Institute of Chicago in 1977; the entryway arch (seen at right) stands outside on the northeast corner of the AIC site. Zion Temple, Chicago. 1884. Demolished 1954. Troescher Building, Chicago. 1884. Demolished 1978. Transportation Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago. Adler & Sullivan. 1893– 94. An exposition building, it was only built to last a year. Louis Sullivan and Charnley Cottages, Ocean Springs, Mississippi destroyed in Hurricane Katrina. Frank Lloyd Wright also claimed credit for the design. Schiller Building (later Garrick Theater), Chicago. Adler & Sullivan. 1891. Demolished 1961. Third McVickers Theater, Chicago. Adler & Sullivan. 1883? Demolished 1922. Thirty-Ninth Street Passenger Station, Chicago. Adler & Sullivan. 1886. Demolished 1934. Standard Club, Chicago. Adler & Sullivan. 1887–88. Demolished 1931. Pilgrim Baptist Church. Adler & Sullivan. 1891. Destroyed by fire January 6, 2006. Wirt Dexter Building. Adler & Sullivan. 1887. Destroyed by fire October 24, 2006. George Harvey House. Adler & Sullivan. 1888. Destroyed by fire November 4, 2006.