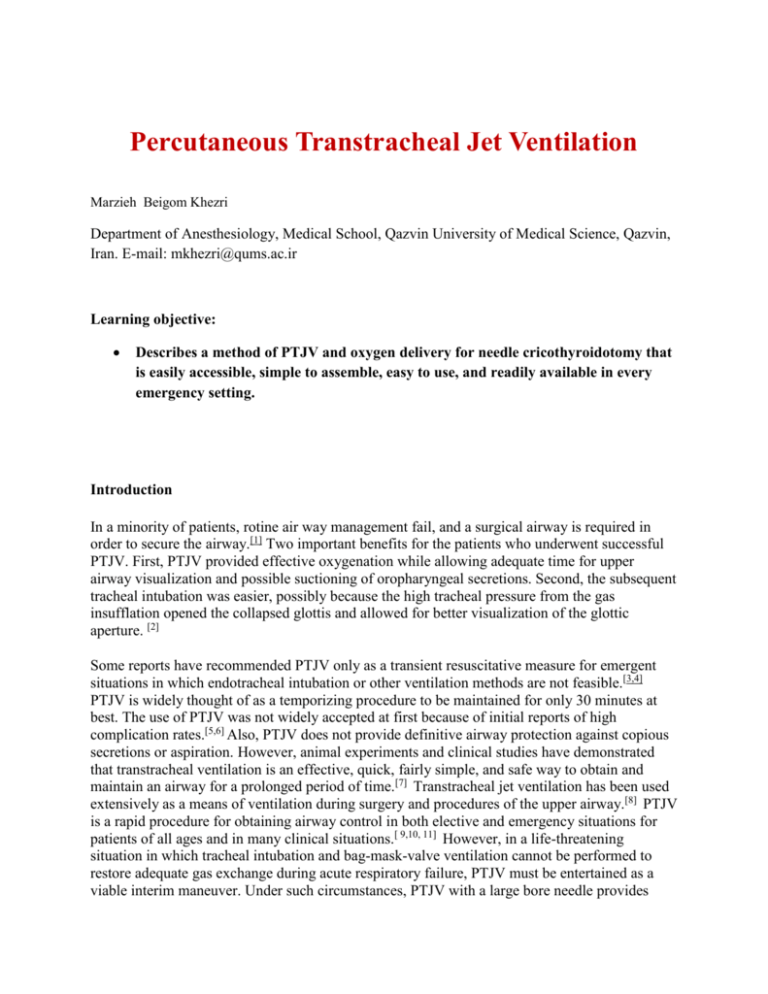

Percutaneous Transtracheal Jet Ventilation

advertisement

Percutaneous Transtracheal Jet Ventilation Marzieh Beigom Khezri Department of Anesthesiology, Medical School, Qazvin University of Medical Science, Qazvin, Iran. E-mail: mkhezri@qums.ac.ir Learning objective: Describes a method of PTJV and oxygen delivery for needle cricothyroidotomy that is easily accessible, simple to assemble, easy to use, and readily available in every emergency setting. Introduction In a minority of patients, rotine air way management fail, and a surgical airway is required in order to secure the airway.[1] Two important benefits for the patients who underwent successful PTJV. First, PTJV provided effective oxygenation while allowing adequate time for upper airway visualization and possible suctioning of oropharyngeal secretions. Second, the subsequent tracheal intubation was easier, possibly because the high tracheal pressure from the gas insufflation opened the collapsed glottis and allowed for better visualization of the glottic aperture. [2] Some reports have recommended PTJV only as a transient resuscitative measure for emergent situations in which endotracheal intubation or other ventilation methods are not feasible.[3,4] PTJV is widely thought of as a temporizing procedure to be maintained for only 30 minutes at best. The use of PTJV was not widely accepted at first because of initial reports of high complication rates.[5,6] Also, PTJV does not provide definitive airway protection against copious secretions or aspiration. However, animal experiments and clinical studies have demonstrated that transtracheal ventilation is an effective, quick, fairly simple, and safe way to obtain and maintain an airway for a prolonged period of time.[7] Transtracheal jet ventilation has been used extensively as a means of ventilation during surgery and procedures of the upper airway.[8] PTJV is a rapid procedure for obtaining airway control in both elective and emergency situations for patients of all ages and in many clinical situations.[ 9,10, 11] However, in a life-threatening situation in which tracheal intubation and bag-mask-valve ventilation cannot be performed to restore adequate gas exchange during acute respiratory failure, PTJV must be entertained as a viable interim maneuver. Under such circumstances, PTJV with a large bore needle provides immediate oxygenation and ventilation by providing adequate gas exchange and ensuring the patency of the airway until a definitive procedure such as oral intubation with bronchoscopy followed by surgical tracheostomy can be performed. It requires fewer instruments and can be performed more quickly than surgical cricothyrotomy. Transtracheal jet ventilation may be used even with partial airway obstruction.[12]PTJV can force oropharyngeal secretions out of the proximal trachea and may force a foreign body out of the proximal trachea (in cases of partial airway obstruction). However, upper airway patency is required for exhalation during PTJV, and an open cricothyrotomy is preferred if significant obstruction exists. PTJV is the surgical airway of choice for children younger than 12 years because of the small tracheal diameter on which an open cricothyrotomy is often impossible. Although rarely performed, needle cricothyroidotomy is a potentially life-saving procedure. The range of adapted equipment presently used for needle cricothyroidotomy is diverse. A surgical airway can be obtained in the emergency setting in 1 of 2 principal methods: surgical cricothyroidotomy Needle cricothyroidotomy.[1, 13] ( provides the simplest, fastest, and safest access.)[2, 5] Cricothyrotomy creates a percutaneous airway through the cricothyroid membrane. Its advantages over tracheotomy are that the membrane is superficial and relatively avascular and cartilage incision is not necessary because the height of the membrane is greater than the distance between the tracheal rings. Cricothyrotomy can be performed with a surgical or cannula (needle) technique, and appropriate use can prevent anestheticrelated deaths. It is a core skill for the anesthesiologist. Indications Complete upper airway obstruction(surgical cricothyrotomy is preferred over PTJV) Temporary measure to establish oxygenation until tracheostomy can be done PTJV is indicated in any situation in which intubation is contraindicated or cannot be achieved.[14] The failure or inability to secure a definitive airway by endotracheal intubation in a timely fashion, and a subsequent inordinate delay in definitive airway control and oxygenation PTJV has also been used electively in patients of all ages and as a rescue procedure. PTJV is the surgical airway of choice for children younger than 12 years of age. Contraindications Absolute contraindications If a definitive airway can easily and rapidly be secured with endotracheal intubation, percutaneous transtracheal jet ventilation (PTJV) is not used. PTJV is not used in the presence of known significant direct damage to the cricoid cartilage or larynx.[14] Relative contraindications If complete upper airway obstruction is present, surgical cricothyrotomy is preferred over PTJV.[15] PTJV can be used in the presence of partial airway obstruction provided that appropriatesized catheters are used.[15] Airway obstruction below the vocal cords that renders exhalation difficult or impossible is a relative contraindication. Equipment Equipment for needle cricothyrotomy and percutaneous transtracheal jet ventilation (PTJV) consists of the following:[4] High-pressure noncollapsible oxygen tubing Needle catheter, 13 or 14 gauge Oxygen source with a flow at 10-15 L/min Manual jet ventilator/insufflator device If a manual jet ventilator/insufflator device is not available, needle cricothyrotomy and PTJV can be performed with equipment that is readily accessible in emergency settings, is simple to assemble, and is easy to use. This equipment includes the following: Oxygen source with a flow at 10-15 L/min(Oxygen could be provided by flashing oxygen at a rate of 15/L/min)16 Commercial bag-valve-mask device (Ambu bag) that includes noncollapsible oxygen tubing and a reservoir bag Large-bore, over-the-needle intravenous catheter (14 ga; 2 in) Plastic syringe, 3 mL, with Luer lock tip, that fits tightly into a 7.5-mm inner diameter endotracheal tube adapte Inner adapter of 7.5 mm endotracheal tube Click here to see video Equipment assembly Connect the intravenous catheter to a 3-mL syringe barrel (with its plunger removed). Connect the 3-mL syringe barrel to a 7.5-mm inner diameter endotracheal tube adapter. Lock the valve of the bag-valve-mask device and connect its oxygen tubing to an oxygen source with a flow at 10-15 L/min. (Oxygen could be provided by flashing oxygen at a rate of 15/L/min)16 Connect the endotracheal tube adapter to the bag-valve-mask device. Manually ventilate at a rate of 1-second compression with 4-second relaxation (ventilations are guided with chest rise). Positioning The patient ideally should be positioned to expose the neck and its landmarks (see image below). If no contraindications are present (eg, known or suspected cervical spine injury), place the patient's head in a hyperextended or "sniffing" position. Extension of the neck aids identification of the anatomy and control of the cricoid space. The cricothyroid membrane is located by identifying the dip or notch in the neck below the laryngeal prominence. The cricothyroid membrane is bounded by the thyroid cartilage superiorly and the cricoid cartilage inferiorly. The landmarks are most easily found by placing the index finger on the prominence of the thyroid cartilage and slowly palpating downward until the finger "drops off" the thyroid cartilage and onto the cricoid membrane. Airway protection during percutaneous transtracheal jet ventilation (PTJV) is attained by positioning the patient to allow drainage of secretions away from the larynx during expiration, so upward gas flow through the larynx causes secretions and blood, for example, to be blown away from the larynx. Technique Before percutaneous transtracheal jet ventilation (PTJV) can begin, a needle cricothyrotomy must be performed. Needle cricothyrotomy Description: Catheter passed through cricothyroid membrane allowing for jet ventilation (oxygenation through small transtracheal catheters) via specialized ventilator. Anesthesia Lidocaine 1-2% at a dose of 2-3 mL is generally sufficient for local skin anesthesia via infiltrative administration in patients who are alert and awake. Injection of a small amount of anesthetic percutaneously into the trachea itself will blunt the cough response as well.( If the patient is alert or concern exists about the cough reflex, prepare another 5mL syringe containing 4 mL of 1% lidocaine with a 25-ga needle). Some advocate that 2 mL of lidocaine be sprayed into the larynx/trachea percutaneously to suppress the cough reflex. o o Attach a small (3-5 mL) syringe containing 1-2 mL of sterile normal saline or water to a large-bore needle (13 or 14 ga). A small bend in the distal 2.5 cm segment of the needle can facilitate advancing the catheter once the trachea has been cannulated. There are also commercially available catheters with a slight bend at the tip specifically for PTJV. While the dominant hand holds the syringe and needle containing saline, with the needle directed caudally at 30-45° to the skin, hold and stabilize the larynx with the nondominant hand. Stabilize the cricoid cartilage with the thumb and middle fingers of the nondominant hand, and palpate the cricothyroid membrane with the nondominant index finger. Insert the needle through soft tissues, the skin, and the cricothyroid membrane. The cricothyroid membrane should be punctured in the inferior aspect (ie, nearer the cricoid Cartilage than the thyroid cartilage) to avoid puncturing the cricothyroid arteries. While exerting negative pressure on the barrel of the syringe, insert the needle through the cricothyroid membrane into the larynx. Air bubbles in the fluid-filled syringe signify entry into the larynx. After entering the larynx, advance the cannula into the larynx and trachea, and then remove the needle. If much resistance is encountered when the needle or catheter is passing through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, or cricothyroid membrane, kinking or bending of the catheter may occur unless a stiffer catheter is used. A small nick in the skin may be needed to facilitate passage through the dermis into the subcutaneous tissue. A percutaneous dilational or Seldinger guidewire technique may result in fewer complications.[ 17,18] Secure the cannula by suturing it to the skin or by placing a circumferential tie around the neck. The proximal end of the cannula must be snug or tightly fitting and securely held around the puncture wound opening. If the cannula is not securely held in place, subcutaneous emphysema may result, the cannula may be dislodged from the larynx, or both. Connect the oxygen source to the cannula. Percutaneous transtracheal jet ventilation A trial of several bursts of oxygen flow is recommended to make certain that the cannula is correctly placed and that the setup is working and ventilating properly. The hypoxic patient should receive 100% oxygen in intermittent bursts < 50 psi at a rate of 20 bursts per minute. For this, an oxygen source capable of 50 psi is needed, along with a regulator to ensure delivery of no more than 50 psi.For children, 30 psi has been recommended. The percentage of inspired oxygen concentration can then be adjusted, depending on blood gas laboratory results. The inspiratory phase or insufflation with the burst of oxygen should last approximately 1 second, and the expiratory phase should last long enough to allow for adequate exhalation, typically 3-4 seconds.[3,19]( slow intermittent rate of 6 breath /min and an inspiratory –expiratory ratio of 1/4) .16 An adequate expiratory phase is important to minimize the risk of barotrauma. Ventilation was controlled by manually opening and closing the valve approximately 12 to 20 times per minute. A successful PTJV was defined as the insertion of an angiocath through the cricothyroid membrane into the trachea and restoration of the pulse O2 saturation to > 90% while using high-pressurized oxygen. An unsuccessful PTJV was defined as the inability to insert the angiocath through the cricothyroid membrane or the inability to insufflate oxygen with the jet ventilator. Pearls To avoid subcutaneous emphysema or a dislodged cannula, be sure to snugly secure the cannula after insertion. A small nick in the skin may be needed to facilitate passage through the dermis into the subcutaneous tissue. Thin catheters may kink or bend in the presence of too much resistance during insertion. Percutaneous transtracheal jet ventilation (PTJV) can be performed in patients of all ages. and it is the surgical airway of choice for children younger than 12 years. Complications Complications with this technique include aspiration, bleeding, pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, barotrauma (eg, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum), catheter-related problems (eg, obstruction or blockage of the catheter, kinking of the catheter, catheter displacement, misplaced or unsuccessful needle or catheter placement),[7] and inadequate ventilation.[ 17,20] The exact incidence of complications with percutaneous transtracheal jet ventilation (PTJV) is not known, but it is thought to be low, considering that the complication rate of translaryngeal puncture alone is in the range of 0.03-0.8%.[13] Disadvantages of PTJV include the following: o o Incomplete control of the airway with subsequent greater potential for aspiration than with a cuffed endotracheal tube Potential for barotrauma (subcutaneous emphysema or pneumothorax) if exhalation is inadequate and airway pressure is elevated References 1. European Resuscitation Council. Guidelines for the advanced management of the airway and ventilation during resuscitation. A statement by the Airway and Ventilation Management of the Working Group of the European Resuscitation Council. Resuscitation. Jun 1996;31(3):201-30. [Medline]. 2. Patel RG. Percutaneous Transtracheal Jet Ventilation A Safe, Quick, and Temporary Way To Provide Oxygenation and Ventilation When Conventional Methods Are Unsuccessful. chest 1689;116(6):1689-1694. 3. Stothert JC Jr, Stout MJ, Lewis LM, Keltner RM Jr. High pressure percutaneous transtracheal ventilation: the use of large gauge intravenous-type catheters in the totally obstructed airway. Am J Emerg Med. May 1990;8(3):184-9. [Medline]. 4. Walls RM. Management of the difficult airway in the trauma patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. Feb 1998;16(1):45-61. [Medline]. 5. Benumof JL, Scheller MS. The importance of transtracheal jet ventilation in the management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. Nov 1989;71(5):769-78. [Medline]. 6. Patel RG. Percutaneous transtracheal jet ventilation: a safe, quick, and temporary way to provide oxygenation and ventilation when conventional methods are unsuccessful. Chest. Dec 1999;116(6):1689-94. [Medline]. 7. Jorden RC. Percutaneous transtracheal ventilation. Emerg Med Clin North Am. Nov 1988;6(4):745-52. [Medline]. 8. Smith RB, MacMillan BB, Petruscak J, Pfaeffle HH. Transtracheal ventilation for laryngoscopy. A case report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. May-Jun 1973;82(3):347-50. [Medline]. 9. O'Connor JV, Reddy K, Ergin MA, Griepp RB. Cricothyroidotomy for prolonged ventilatory support after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. Apr 1985;39(4):353-4. 10. Carden E, Ferguson GB. A new technique for micro-laryngeal surgery in infants. Laryngoscope. May 1973;83(5):691-9. [Medline]. 11. Chong CF, Wang TL, Chang H. Percutaneous transtracheal ventilation without a jet ventilator. Am J Emerg Med. Oct 2003;21(6):507-8. [Medline]. 12. Ward KR, Menegazzi JJ, Yealy DM, Klain MM, Molner RL, Goode JS. Translaryngeal jet ventilation and end-tidal PCO2 monitoring during varying degrees of upper airway obstruction. Ann Emerg Med. Nov 1991;20(11):1193-7. [Medline]. 13. Leibovici D, Fredman B, Gofrit ON, Shemer J, Blumenfeld A, Shapira SC. Prehospital cricothyroidotomy by physicians. Am J Emerg Med. Jan 1997;15(1):91-3. [Medline]. 14. Yealy DM, Stewart RD, Kaplan RM. Myths and pitfalls in emergency translaryngeal ventilation: correcting misimpressions. Ann Emerg Med. Jul 1988;17(7):690-2. [Medline]. 15. Yealy DM, Menegazzi JJ, Ward KR. Transtracheal jet ventilation and airway obstruction. Am J Emerg Med. Mar 1991;9(2):200. [Medline]. 16. Donlon JV,Doyle JD,Feldman A M.Anesthesia for eye ,ear,,nose, and throat surgery in miller anesthesia ,2005 ,Chichill levingstone , 2547. 17. Ciaglia P, Brady C, Graniero KD. Emergency percutaneous dilatational cricothyroidostomy: use of modified nasal speculum. Am J Emerg Med. Mar 1992;10(2):152-5. [Medline]. 18. Ophir D, Konichezky S. Minicricothyrotomy for tracheobronchial toilet. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. May 1990;99(5 Pt 1):337-9. [Medline]. 19. Spencer CD, Beaty HN. Complications of transtracheal aspiration. N Engl J Med. Feb 10 1972;286(6):304-6. [Medline]. 20. Flory FA, Hamelberg W, Jacoby JJ, Jones JR, Ziegler CH. Transtracheal resuscitation. J Am Med Assoc. Oct 13 1956;162(7):625-8. [Medline].