Make In India And Challenges Before Defence Manufacturing

advertisement

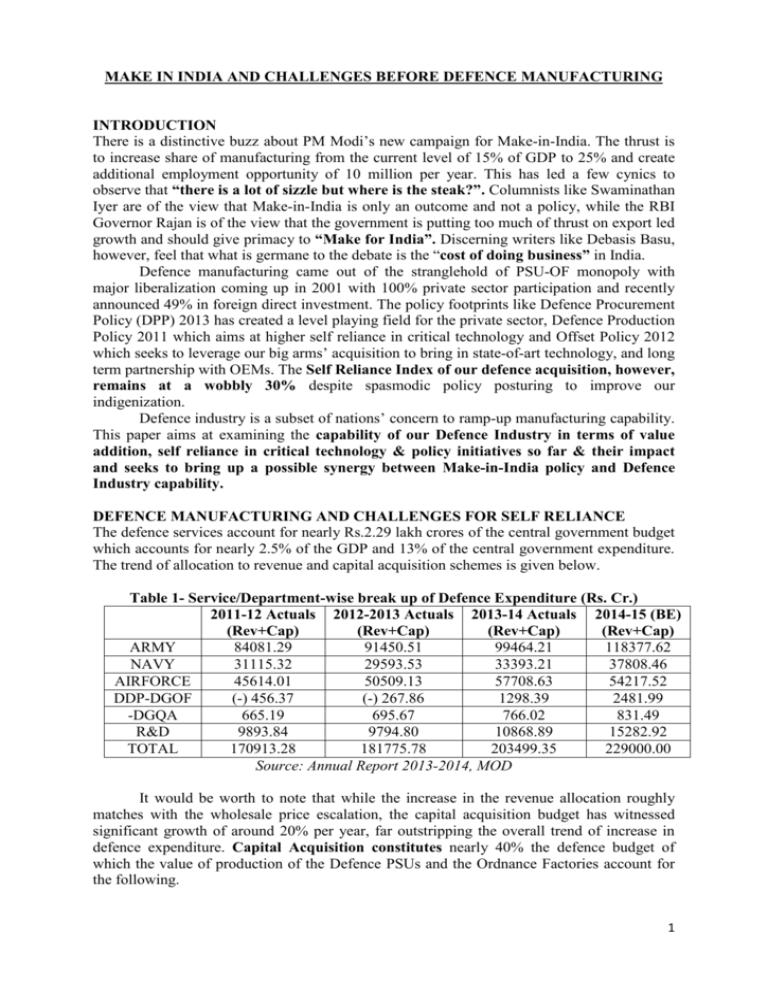

MAKE IN INDIA AND CHALLENGES BEFORE DEFENCE MANUFACTURING INTRODUCTION There is a distinctive buzz about PM Modi’s new campaign for Make-in-India. The thrust is to increase share of manufacturing from the current level of 15% of GDP to 25% and create additional employment opportunity of 10 million per year. This has led a few cynics to observe that “there is a lot of sizzle but where is the steak?”. Columnists like Swaminathan Iyer are of the view that Make-in-India is only an outcome and not a policy, while the RBI Governor Rajan is of the view that the government is putting too much of thrust on export led growth and should give primacy to “Make for India”. Discerning writers like Debasis Basu, however, feel that what is germane to the debate is the “cost of doing business” in India. Defence manufacturing came out of the stranglehold of PSU-OF monopoly with major liberalization coming up in 2001 with 100% private sector participation and recently announced 49% in foreign direct investment. The policy footprints like Defence Procurement Policy (DPP) 2013 has created a level playing field for the private sector, Defence Production Policy 2011 which aims at higher self reliance in critical technology and Offset Policy 2012 which seeks to leverage our big arms’ acquisition to bring in state-of-art technology, and long term partnership with OEMs. The Self Reliance Index of our defence acquisition, however, remains at a wobbly 30% despite spasmodic policy posturing to improve our indigenization. Defence industry is a subset of nations’ concern to ramp-up manufacturing capability. This paper aims at examining the capability of our Defence Industry in terms of value addition, self reliance in critical technology & policy initiatives so far & their impact and seeks to bring up a possible synergy between Make-in-India policy and Defence Industry capability. DEFENCE MANUFACTURING AND CHALLENGES FOR SELF RELIANCE The defence services account for nearly Rs.2.29 lakh crores of the central government budget which accounts for nearly 2.5% of the GDP and 13% of the central government expenditure. The trend of allocation to revenue and capital acquisition schemes is given below. Table 1- Service/Department-wise break up of Defence Expenditure (Rs. Cr.) 2011-12 Actuals 2012-2013 Actuals 2013-14 Actuals 2014-15 (BE) (Rev+Cap) (Rev+Cap) (Rev+Cap) (Rev+Cap) ARMY 84081.29 91450.51 99464.21 118377.62 NAVY 31115.32 29593.53 33393.21 37808.46 AIRFORCE 45614.01 50509.13 57708.63 54217.52 DDP-DGOF (-) 456.37 (-) 267.86 1298.39 2481.99 -DGQA 665.19 695.67 766.02 831.49 R&D 9893.84 9794.80 10868.89 15282.92 TOTAL 170913.28 181775.78 203499.35 229000.00 Source: Annual Report 2013-2014, MOD It would be worth to note that while the increase in the revenue allocation roughly matches with the wholesale price escalation, the capital acquisition budget has witnessed significant growth of around 20% per year, far outstripping the overall trend of increase in defence expenditure. Capital Acquisition constitutes nearly 40% the defence budget of which the value of production of the Defence PSUs and the Ordnance Factories account for the following. 1 Table 2- Value of production and value addition PSUs and OFB (Rs. In Crore) Name of PSUs 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 Value Addition HAL 12693.19 14201.82 15296.00 39% BEL 5793.58 6290.00 6140.00 41% BEML 4077.19 3359.70 3201.32 39% MDL 2523.69 2290.64 2709.00 23% GRSE 1293.80 1529.37 1550.83 35% GSL 676.40 506.62 512.24 37% BDL 992.94 1177.00 1793.43 50% MIDHANI 496.00 537.37 555.04 57% HSL 564.04 483.84 403.22 OFB 12390.72 11984.00 11234.00 85% TOTAL 41501.55 42360.36 43395.08 50% Source: Annual Report 2013-2014, MOD It would be seen from the above that while the average yearly increase in VOP of Defence PSUs is around 5% per year, in case of the OFs it is only 2%. It would be interesting to note that the value addition of different defence PSUs vary between 23% to 57% while it is very high (85%) for OFB. PSUs like HAL and MDL show a poor level of value addition as they are largely system integrators, while Midhani & BDL have contributed handsomely to indigenization. The higher indigenization in case of OFB is largely attributable to the low end technology. India has been historically availing of technology through licence agreements from Russia and a smattering of western countries. The exceptions are some of the missile systems, small arms and their ammunition and tanks where technology has been indigenously developed by the DRDO. The LCA with Final Operational Clearance (FOC) will hopefully be a major Make-in-India platform. It must be mentioned that indigenization has effected substantial reduction in cost of the systems due to India’s labour arbitrage, good facilities and fairly well trained labour force. The following table brings out the cost saving of a few major products through the technology transfer route. Table 3-Indigenization & Cost Savings through TOT Product Indigenization Cost Saving Milan 71% 60% Konkur 70% 30% HAL SU-30(Air Frame) 55% 45% SU-30 Engine 65% 45% HAWK 40% 18% MEDAK ICV 90% 50% MIDHANI Titanium Alloy 60% 15% BEL Sonoboys 70% 30% Source: Table prepared by Author based on data obtained from DPSUs/OF DPSU/OF BDL SELF RELIANCE TRENDS The self reliance trends in defence acquisition show a dismal picture. A committee under Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam, the then SA to RM, had recommended India should ramp-up this quotient from 30% (1995) to 70% by (2005). The following table, however, brings out how the self reliance index has remained sticky around 30%. 2 Table 4-Total Acquisition and SRI: Trends Total Acquisition Indigenous Acquisition Self Reliance % Cost (Rs. Cr) Cost (Rs. Cr) 1993-94 399 1200 30% 2000-01 11164.5 3400 31% 2005-06 24464 7828 32% 2009-10 38258 12251 32% 2012-13 49578 26260 35% Source: Table Prepared by Author based on data obtained from Ministry of Defence Year The principal reason for this state of affair is our poor design capability in critical technologies, inadequate investment in R&D and our inability to manufacture major subsystems and components. The technology transfer route has provided India with the know how without providing the clue for know why. It is because of this reason that even for an upgrade of the systems, the defence PSUs are critically dependent on the original licensors. A case in point is SU-30 upgrade where the Russians often take HAL to ransom. The following table brings out the gaps in critical technology of different systems. Sl. No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Table 5- Critical Technology & Gaps System Gaps Gas Turbine Engine (a) Single Crystal and Special Coating in Turbine Blades FADEC Missile Uncooled FPA seekers Aeronautics Smart Aerostructures Stealth Technology Material Nano Material, Carbon Fibres Naval Systems Super Cavitating Technology Sensors AESA, Radar, RLG, INGPS Communication Software Defined Radio Avionics Gen III, II Tubes Surveillance UAVs, Satellites Source: DRDO, BEL and HAL From the foregoing it would be seen that the major deficiency in terms of capability are in the areas like propulsion, weapons and sensors. Some of the critical technologies where the progress made by DRDO has been abysmally poor are Focal Plane Array (FPA), Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) Radar and Stealth Technology India is presently engaged in design and production collaboration for a Fifth Generation Fighter Aircraft (FGFA) with the Russians for a stealth aircraft. PROCUREMENT, PRODUCTION & OFFSET POLICY IN RETROSPECT & THEIR IMPACT The Defence Procurement Policy 2013 envisages higher preference to Buy (India), Buy and Make (India), and Make options over the earlier thrust towards Buy (Global) or the import option. It ostensibly looks at creating a better level playing field between the public and private sector with greater impetus towards indigenization. A major departure from the previous policy is allowing the private Indian industry to avail of technology transfer which was the exclusive domain of DPSUs/Ordnance factories earlier. The policy also encourages Joint Venture with OEMs. PM Modi’s Make-in-India campaign has added another 3 category to Defence Acquisition though it would include cases coming under the panoply of ‘Buy’ and Make and ‘Make’ where technology is indigenously developed. The Offset Policy guidelines (2012) have for the first time has allowed TOT through the JV or through non equity route. It has also allowed multiplier for critical technology areas like FPAs, Nano Technology based sensor, fiber laser technology & THZ technologies, which was alluded to above. The Defence Production Policy (2011) aims at achieving substantive self reliance in design, development and production of critical subsystems by forming consortia, JVs by involving academia and R&D institutions. It also promised to set up a set up a defence technology fund to support public, private sector as well as academic and scientific institutions for pursuing high end research. The impact of all such policies on FDI inflow, export, augmentation and long term partnership has been quite disappointing. The reasons are enumerated below. FDI Policy The OEMs for setting up business in India in partnership with public/private players want to have a major say in the management of manufacturing. While the announcement to upscale the FDI limit from 26% to 49% in the last budget has been a step in the right direction, it is unlikely to enthuse reputed global manufacturing houses to set up manufacturing bases and bring in front end technology though some joint venture intents has been evinced for companies like the TATAs. On the other hand countries like China and South Korea have become major manufacturing hubs in aeronautics and ship building technology by being very liberal in their FDI policy and providing high modicum of ‘Ease of Doing’ business compared to India. R&D Allocation Besides the FDI policy, inadequate investment in R&D and lip service to technology funding by making a token allocation of Rs.100 crore to Defence Technology Fund in the last budget is adequate commentary on our lack of seriousness in the area of research and development. The allocation to DRDO remains sticky around 6% of defence expenditure though successive parliamentary committees have recommended a minimum allocation of 10%. The private sector giants like the TATA, L&T and Mahindra and Mahindra invest less than 1% of their turn over in R&D unlike countries like France where corporate invest more than 10% in R&D. It would be also be interesting to note that the overall allocation to R&D is significantly lower (0.85%) in India compared to advanced countries which spend in the range of 2.2% to 3.5%. The following table would bring out the trend. Table 6-Major R&D Spenders in the World Vis-à-vis India Country 2012 2013* GERD (PPP R&D as % of GERD (PPP R&D as % of US$ Billion) GDP US$ Billion) GDP US 418.6 2.68 423.7 2.66 Japan 159.9 3.48 161.8 3.48 Germany 90.9 2.87 91.1 2.85 South Korea 55.8 3.45 57.8 3.45 France 50.4 2.24 50.6 2.24 India 40.3 0.85 45.2 0.90 Note. *: Figures for 2013 are forecast; GERD: Gross Expenditure on R&D Source: Battelle and R&D Magazine, 2013 Global R&D Funding Forecast, December 2012. 4 Manufacturing It accounts for 14-16% of GDP with 85% of employment in unorganized sector, with a ‘missing middle’, unlike manufacturing hubs in Korea, China, Germany and Japan where 50% of the firms are large with benefit of economy of scale and 20% are SEMs. Value addition in global value chain for India was only 1% in 2009 as against 9% by China and Germany. National manufacturing Zone (NMZ) 2011 policy is limping big time in the absence of Centre State synergy, tardy land acquisition and long drawn environmental clearance. Subir Gokran has rightly observed that increase in Incremental Capital Output Ratio (ICOR) from 3.1% (2005-2006) to 5.9% (2012-2013) is largely attributable to supply constraints like power-coal imbalance and in ordinate project delays. Export Promotion The following table provides a trend analysis of exports by Defence PSUs and Ordnance Factories since 2008-09 Year 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 Table 7-Export Performance of DPSUs/OFs (Rs. Crore) VOS % Increase Exports 27237.1 15.0 854.38 33995.9 24.8 477.7 36537.9 7.5 653.6 40499.4 10.8 730.0 40956.2 1.1 755 41001 0.1 768 Source: Annual Report, MOD % Increase 36.0 -44 36.8 11.7 3.5 1.7 Of the PSUs/OFB, HAL & BEL account for 66% of exports. Export as share of VOS has remained around 3% for HAL and around 3-4% for BEL thereby showing the policies so far have not impacted on their export performance. Raghuram Rajan sounds a note of caution regarding the obsession for export led growth by heavily subsidizing inputs at the cost of fostering domestic demand. His call for Make for India to supplement Make-in-India is an extremely welcome alternative. Impact of Offset Contracts After promulgation of this policy in 2005, 24 contracts have been signed for $4.8billion. However discerning analysts observe that the expected benefit in terms of FDI inflow, high end technology, increased export and outsourcing have not taken place. The C&AG in its performance audit of Fleet Tanker Contract (2010) has brought out how full benefit of offset provision has not been availed from the OEM. Further C&AG’s comprehensive report of 2012 on offset contracts severely castigates the inept contractual arrangement that underlay such offset arrangements and additional cost implication. MANUFACTURING, MAKE IN INDIA POLICY AND DEFENCE MANUFACTURE The sectoral share of primary, secondary and tertiary segments show a tectonic shift since liberalization wafting through the corridors since 1990s. The share of agriculture in GDP shows a significant reduction while the share of industry has remained stagnant and the service sector showing the way as the sunshine sector. The following table brings out the trends in the compositional shift. 5 Sector Primary Secondary Tertiary Table 8-Sectoral Share of GDP 1950-1951 1990-1991 55 33.1 14.7 24.2 30.3 42.7 Source: CSO 2013-2014 15 25 60 A disaggregation of the secondary sector shows that the share of manufacturing sector has remained constant around 15% which is now targeted to increase to 25%. The experience of manufacturing giants like Germany, South Korea and China reveal that manufacturing account for 30% of their GDP. Therefore the thrust of the government to encourage Make-inIndia option by facilitating the enabling environment to manufacture, improving ease of doing business, encouraging creation of national manufacturing zones in tandem with the states and investing one trillion dollar through PPP route in the infrastructural sector make eminent sense. Prof. Basu rightly observes out that the success of the Make Indian policy will critically hinge on cost of doing business in India. The two critical factors for this would be the quality of human resources and cost of capital. India’s education system is presently mired in a mess and need millions of skilled workers coming out of ITI with quality training. While access to education at the primary level through Right to Education has improved access significantly, the quality deficit, both in the primary segment and higher education is palpable. While the private sector has contributed handsomely to the growth of technical and management education, the quality of education and lack of research impact on the employability of students adversely despite the global opportunity. As regards cost of capital, the following table would bring out the distributing trend of exorbitant cost of capital in India compared to the developed countries. Table 9-Cost of Capital: Global Comparison Country 10 years Govt. Bond Inflation (CPI) USA +2.16 +1.7 Japan +0.41 +2.7 Euro Area +0.68 0.5 Brazil Russia India China 12.5 12.44 7.91 3.67 Source: The Economist- 13th December, 2014 6.3 7.6 7.3 2.1 What is interesting also to note that most of the BRIC countries are bedeviled by high cost of capital and unacceptable level of inflation accentuating their “Misery Index”. Importance of Total Factor Productivity Prof. Solow, a Nobel Laureate, in his seminal paper had brought out the importance of factor productivity. His equation Q=A * K∆ Lβ where Q is the production function, A is the level of technology and scale, K & L are factors of production ∆ & β are factor efficiency has demonstrated how US has become the premier technological hegemon after the second world war. A case in point is the phenomenal growth in China from 1979 as would be evident from the following table. Almost 50% of the GDP growth is attributable to total factor productivity growth. 6 Table 10- Sources of Growth in China Parameter 1953-1978 1979-1994 Output Growth 5.8 9.3 Capital Input Growth 6.2 7.7 Labour Input Growth 2.5 2.7 TFP Growth 1.1 3.9 Contribution of Production 18.0 41.6 Source: A.P. Thirlwall - Economics of Development-Theory and Evidence LESSONS FOR INDIA’S DEFENCE INDUSTRY The defence industry in India cannot be impervious to these trends. It has to be sensitive to the skill requirements in order to absorb high technology which comes as part of TOT. One of the predominant reasons for Japan’s phenomenal growth since 1950s has been their highly skilled labour force which could absorb front end technology from US quickly and adopt them to harness commercial success through dual use technology. The success of Japan in electronics and automobile is testimony to this. In India, on the other hand, the TOT experience reveals that the technology absorption has been inordinately slow leading to continued dependence for our foreign collaborators well beyond the originally contracted period. Experience of HAL in terms of production of MIG series Aircraft and SU-30, and MDL for producing Scorpion submarines are grim reminders of our poor high skill absorbing capability. CONCLUSION India is witnessing a significant stickiness in its manufacturing sector which is bedeviled by huge presence of small scale and informal sector that are bereft of requisite skill levels and economy of scale. Their access to capital is also seriously constrained. However the manufacturing sector provides a wonderful opportunity for India to be part of the global supply chain and generate high levels of employment opportunity to absorb around 10 million young Indian who will come to the market in search of employment every year. They also need to be properly skilled and trained and networked with their global peers. The defence industry, be it public sector or private, has to be part of the national manufacturing policy mosaic. Unfortunately the defence sector often chooses to distance itself in its interface with other civilian sectors. There is opportunity aplenty in sectors like Aerospace and Ship building where there is considerable civilian and military market. Lack of design capability to manufacture critical subsystems remains a huge handicap. DRDO remaining mired in inordinate delay, huge cost over runs and deficient in critical technology areas like ‘seekers’ and ‘stealth’. Tokenism like Rs.100 crore allocation towards Technology Acquisition Fund or a lip service to FDI policy by increasing to 49% are not the way forward. Public private partnership, joint venture with foreign OEM and design houses will require bolder policy like higher FDI ceiling higher than 50%, a political will to mentor and hold hand of different stake holders who are often at cross purposes. The new PM has set his foot in the right place; the defence ministry, however, has to match his steps, shed its ghetto mentality and strive for better synergy with other manufacturing sectors to make “Make-in-India” the piped piper in the days ahead. Dr. S.N. Misra, Formerly, JS Aerospace, MOD (Views expressed are personal) 7