RIBA Awards Religious Buildings Category Introduction by Martyn

advertisement

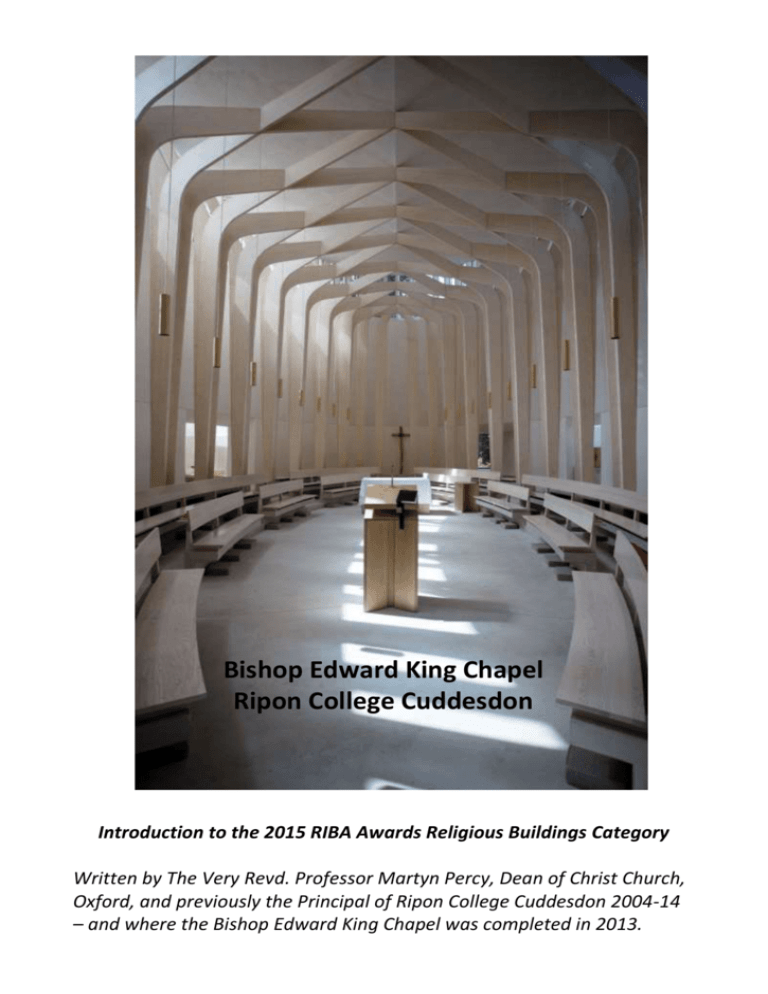

Bishop Edward King Chapel Ripon College Cuddesdon Introduction to the 2015 RIBA Awards Religious Buildings Category Written by The Very Revd. Professor Martyn Percy, Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, and previously the Principal of Ripon College Cuddesdon 2004-14 – and where the Bishop Edward King Chapel was completed in 2013. Although it is something of a cliché, most people will know that churches are essentially ‘sermons in stone’. That is to say, the very design, layout and physicality of a church building convey spiritual sentience and religious resonance. To try and ‘read’ a church otherwise is to entirely misunderstand its purpose: gathering for worship. Churches are spaces that take us to another place. They point us upward to God, inward to reflect, and outward to a world that is both created and awaiting redemption. We, as clients, were deeply fortunate – I should say blessed, really – to have an architect in Niall McLaughlin who understood that our new Chapel could only ever be a sermon in stone. To be sure, everyone knows what stone is; and they might assume they know what a sermon is too (i.e. often lengthy, ponderous, and dull…?). But a sermon is, strictly speaking, a small comment – an expansion and reference which only refers us back to the scriptures. A sermon in stone is merely a comment on what God has already revealed in words. Niall McLaughlin’s design – essentially a ship, or large coracle – is rooted in a remarkable Gaelic Christian legend, and recounted in a famous story by Seamus Heaney (Selected Poems, from ‘Seeing Things’, 1991): Lightenings viii The annals say: when the monks of Clonmacnoise Were all at prayers inside the oratory A ship appeared above them in the air. The anchor dragged along behind so deep It hooked itself into the altar rails And then, as the big hull rocked to a standstill, A crewman shinned and grappled down the rope And struggled to release it. But in vain. 'This man can't bear our life here and will drown,' The abbot said, 'unless we help him.' So They did, the freed ship sailed, and the man climbed back Out of the marvellous as he had known it. The story, much like McLaughlin’s architecture, leans on ancient ideas of Christian space. The ‘nave’ of a church comes from the same term from which we derive the word ‘naval’. One of the earliest Christian symbols, apart from the cross, was that of a ship – conveying the idea of pilgrimage – the soul in transition, or the journey from this life to the next. More specifically, one thinks of the boat tossed on the storms of Sea of Galilee and the fear of the disciples – yet the boat does not sink because of the presence of Jesus (Matthew 8: 23-27). The story, taken as literal or as metaphor, simply says, ‘you will not be overcome’ by the storms of life; be still, have faith, and trust in God. The spiritual relationship between individuals, communities and their buildings is always a complex one. Yet sometimes, the simplest things are also the most difficult to produce. McLaughlin’s great skill was to be able to not only tell a simple story of salvation, but to create and interpret that sermon in stone within the award-winning Bishop Edward King Chapel at Cuddesdon. McLaughlin has created a uniquely holy space that anchors women and men in their evolving vocations and discipleship. The building provides a unique, inspiring and beautiful frame of reference that is open in character and texture. For many people the ‘implicit theology’ of the new Chapel will not be obvious at first sight. Yet if you encounter the space in stillness, you quickly absorb the sense of the use of light, space, materials and design – all combining to produce an awareness of being carried and held, yet also freed and offered. The relationship between the Chapel and the worshippers becomes essentially perichoretic – the ‘mutual indwelling’ of materials and spiritual currents that blend and inter-penetrate, producing new spiritual meanings, whilst also maintaining distinctive sodalities. The use of colour (bare, minimal) means that the natural light does all the work, and the worshipper is simply left with a sense of being bathed in warm, numinous buttermilk. The Chapel does not seek to impose; yet it cannot fail to inspire. Most people, when they enter the Chapel for the first time, simply gasp – and then whisper a single word: ‘wow’. Then they fall silent, subsumed by the simplicity and intricacy of it all.