Programme - The British Empire at War Research Group

advertisement

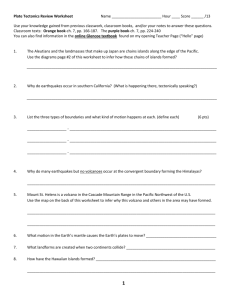

Islands of War, Islands of Memory 5-7 April, 2013 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Programme for Friday 5 April 2013 1.00pm – 2.15pm: Registration and coffee Islands of memory, islands of community 2.15 – 2.40pm: Jacqui Leckie: Islands and Intimate memories: ‘Kai Amerika’ children of Fiji from the Pacific War. 2.40 - 3.05pm: Marek Jasinski: A farewell to Utøya: Painful legacy and creation of heritage. 3.05 – 3.30pm Jonathan Sweet: ‘World Within’ no more: The shaping of heritage in the Kelabit Highlands, Borneo. 3.30- 3.55: Coffee 3.55 – 4.20pm Alexander Debono: Malta: Post-war cultural narratives of a Mediterranean island. 4.20-4.45: Hazal Papuccular: Dodecanese Islands in the Second World War: Islands of war, hunger and migration. 4.45 – 5.05: Irene Lagani: Post war legacies in the island of Cythera: oblivion versus historical memory. 5.05 – 5.45pm: Discussion (led by convenors) Conference posters will be on display in the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research (Posters by Hedda Askland & Thushara Dibley) 6-8pm – Informal Conference Welcome by Convenors followed by Drinks Reception in the Senior Combination Room, St Catharine’s College Programme for Saturday 6 April 2013 10.00 – 10.10: Welcome address (Gilly Carr and Keir Reeves) Islands of heritage, islands of war 10.10 – 10.35: Gilly Carr: Islands of obsession, islands of nostalgia: the afterlife of the German Occupation in the British Channel Islands. 10.35 – 11.00: Brent Fortenberry and Andrew Baylay: From across the sea: Boer POWs in 20th Century Bermuda. 11.00 - 11.25: Daniel Travers: Part of the Landscape: The HMS Royal Oak and Italian POWs in Orkney's Contemporary Culture and Remembrance 11.25 – 11.55: Coffee 11.55 – 12.20: Nota Pantzou: War Remnants of the Greek Archipelago: Persistent memories or fragile heritage? 12.20 – 12.45: Artemi Alejandro-Medina: A place in the sun: Negotiating Franco’s World War II hidden heritage in the Canary Islands and its tourist development. 12.45-1.10: Questions and discussion 1.10 – 2.10: Lunch Islands of tourism, landscapes of war 2.10 – 2.35: Federico Lorenz: What did the war mean for Islanders? Legacies of the Malvinas / Falklands War in the Patagonic Islands. 2.35 – 3.00: Linda Riddell: The Importance of Geography: The Experience and Commemoration of Two World Wars in Shetland. 3.00 – 3.25: Stephen A. Royle: War, memory and heritage from the Falklands Conflict of 1982. 3.25 – 3.55: Coffee 3.55 – 4.20: Richard Butler: The legacy of war in the Northern Isles: varying aspects of heritage in Orkney and Shetland. 4.20 – 4.45: Beate Feldmann Eellend: ‘Post-military landscape on islands in the Baltic Sea Area. 4.45 – 5.30: Discussion (discussant: Gilly Carr) From 5.30-6.30pm, Sheila Lecoeur’s film, A Basket of Food: Greece in the 1940s will be shown. 7.15pm: Conference dinner at University Centre (please follow organisers) Programme for Sunday 7 April 2013 Islands of war, islands of memory 9.30: Coffee 10.00 – 10.25: Keir Reeves and Joseph Cheer: “I Gat Wol Wo II”: Remembering Melanesia’s enduring World War Two heritage. 10.25 – 10.50: Ryoji Aritsuka: Post-traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSS) in the battle in Okinawa islands in Japan 1945. 10.50-11.15: Kris Liaugminas: Marshall Law: the Legacy of Containment and the American Nuclearization of the Marshall Islands in the Cold War 11.15-11.45: Coffee 11.45-12.10: Ian Kinane: Theatre of War: Survivor: Palau as a Pacific 'Lieu de Mémoire'. 12.10 – 12.35: Elena Mamoulaki: An island of (no) outcasts: Memories of war, exile and cohabitation on Ikaria. 12.35 – 1.00: Questions and discussion 1.00 – 2.00: Lunch Islands of war, islands of contested memory and difficult heritage 2.00 - 2.25: Geoffrey White: (De)Colonizing Island Memories of World War II. 2.25 – 2.50: David Watters: The heritage of World War II across the disparate Caribbean region. 2.50 – 3.20: Coffee 3.20 – 3.45: Sheila Lecoeur: Memories and conflicting memories of occupation and war in the Cyclades islands, 1941-5. 3.45 – 4.10: Robert van Ginkel: The Memorialisation of the ‘Russians’ War’ on the Island of Texel. 4.10 – 5.00: Discussion (discussant: Keir Reeves). Conference disperses Convenors Keir Reeves Keir Reeves is based at Monash University in Australia where he is a Senior Monash Research Fellow in the School of Journalism, Australian and Indigenous Studies where his current research in concentrated on Asia and the Pacific cultural heritage and history. He is currently involved in two major Australian Research Council projects that interrogate war and memory. In 2013 he is a Visiting Fellow at Clare Hall Cambridge and is also a visiting researcher in the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research where he is working with the Cambridge Heritage Research Group in the Department of Archaeology. Keir’s publications include co-editing (contributing) Places of Pain and Shame Dealing with ‘difficult heritage’ (Routledge, 2009) with Bill Logan and more recently he has been a jointauthor on the Bruce Scates led Anzac Journeys: Walking the Battlefields of the Second World War (Cambridge University Press, 2013). He has recently published on heritage, history and travel in Annals of Tourism Research, International Journal of Heritage Studies, Tourism Analysis, Landscape Research,,Australian Historical Studies and Critical Asian Studies. With Dr Gilly Carr, Keir is co-convening Islands of War, Islands of Memory. Gilly Carr Gilly Carr is a Senior Lecturer and Academic Director in Archaeology at the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Continuing Education. She is also a Fellow and Director of Studies in Archaeology and Anthropology at St Catharine’s College. Her fieldwork is currently based in the Channel Islands, where she has worked and published extensively on the archaeology, heritage and memory of the German occupation. Her latest book, Legacies of Occupation: archaeology, heritage and memory in the Channel Islands, is forthcoming. She also works with former deportees who were sent to German internment camps during WWII. Her museum exhibition, Occupied Behind Barbed Wire, was on display in Guernsey and Jersey Museums in 2010 and 2012 respectively. Other publications include ‘Prisoners of War: Archaeology, memory and heritage of 19th and 20th century mass internment’ (Springer 2012) and ‘Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War: Creativity behind barbed wire’ (Routledge 2012), both co-edited with Harold Mytum. Abstracts and Biographies (alphabetical order) Ryojij Aritsuka The islands of Okinawa are situated in the most southern part of Japan, where the independent country of the Ryukyu Kingdom had been before the forced occupation by Japan 1871. At the end of WWII, the Japanese Government intended to gain more time before the landing operations by US Army on the mainland, at the sacrifice of the islands of Okinawa. The Japanese Army in Okinawa numbered 70,000 troops. They were very obviously outnumbered by US troops, who numbered 550,000 men. To gain more time, the Japanese army allowed the Americans to invade, while themselves withdrawing to the southern end of the island, where 200,000 people were living. They demanded that these people leave their homes and hand them over to the Japanese soldiers along with their food. Thus, with no access to shelters, many inhabitants died in the US bombing. Men between the ages of 14 and 60 were forced to fight as untrained soldiers after the Americans landed on 1 April 1945. Families, along with Japanese soldiers, sometimes hid or took shelter in caves, but when the island babies inevitably started to cry, Japanese soldiers killed them or forced their mothers to kill them in case they alerted the American troops to the presence of the soldiers. Further, islanders were not allowed to surrender to the Americans or become prisoners; if they tried to surrender, they were killed by Japanese soldiers. In any case, the Japanese suspected the Okinawan islanders of being US spies because they could not understand their language. Because of the prohibition against surrender, Japanese soldiers indirectly encouraged islanders to commit suicide. They distributed hand grenades to local people, telling them that the Americans would kill all the men and rape the women. People were scared of both the Japanese and American troops. They were most of all afraid that Japanese soldiers would kill them if they were captured alive by the Americans. Thus, the senior members of families sometimes killed their own family members using the hand grenades rather than be taken prisoner. This is today referred to as a ‘mass suicide’, and over 1,000 people’s lives were taken in this way; hundreds were killed by Japanese soldiers. As a result of such a cruel war, 20% of the total Okinawan population of 450,000 people died. Added to this number are the untrained Okinawan soldiers who died. In total, 126,000 local inhabitants were killed between 10 October 1944 (when the bombing began) and 7 September 1945 (when the battle ended). The event is highly traumatic in local memory such that we can find many types of post-traumatic stress syndromes of old civilian people in Okinawa even now. In my paper I will discuss the many kinds of PTSS. Ryoji Aritsuka, M.D., is Chief of the Department of Psychiatry, Okinawa Cooperative Hospital, Naha City, Japan. He was born in 1947, and graduated from the medical school of Hirosaki University. He is a member of Association of European Stress Trauma and Dissociation, and a former member of Confederation of European Firms, Employment Initiatives and Cooperatives for people with mental health problems. (CEFEC; http://socialfirmseurope.org/). Artemi Alejandro-Medina Nazi Germany was supported in the Second World War by Franco’s dictatorship. The Canary Islands (Gran Canaria) were an important geo-strategic place for the Axis and Allies. During the war Franco hurried into fortifying the islands with an anti-invasion plan along the coastal line. Also, as part of a larger scale project; a U-Boat bunker pens, a new navy base and the Manuel Lois barrack, an underground torpedoes warehouse, were built. The economic, technical and human effort deployed was colossal in an exhausted Spain after the Spanish Civil War.Franco’s propaganda apparatus worked during 40 year to create a distorted reality of the Spanish role played in the Second World War. Today the access to the archives is still difficult and this period of History a sensitive issue. The oral memory mixes up legend and truth. However the use of archaeology for the study of the 20th century has opened a new field of interpretation.This paper is focusing on the Francoist heritage in the Canary Islands, specifically from the Second World War. Also, it claims for a social and tourist use of it as the best way of preservation for it. Artemi Alejandro-Medina is Director of Archaeology at Patrimonia Consulting. He is also working for the Pilgrim Archaeological Project, which is focusing in the Canary Islands and the Second World War heritage. He is currently a PhD candidate for the Universidad de Gran Canaria. His fields of interest are conflict archaeology, community projects and cultural and tourist development. Hedda Haugen Askland and Thushara Dibley In 2002, Timor-Leste—a nation marked by centuries of colonial control, military rule, oppression and war—celebrated the realisation of independence. For the past two years, the country had been under United Nations transitory administration following the retreat of the 24-year-old Indonesian occupational regime. Since then, the two consecutive periods of colonisation and war, the Portuguese and the Indonesian, have marked the historical layers of the Timorese nation and become prominent characteristics of the Timorese people’s national identity; whilst different historical narratives and cultural memories exist, the Portuguese era and the resistance motif have dominated public discourse. This paper briefly considers how these historical memories emerged as dominant national narratives following independence and reflects on how the subsequent lack of public attention to competing historical narratives formed part of the nation’s progress towards stability and peace. It considers these issues through an analysis of how political, social and cultural memories formed part of the political crisis that occurred in East Timor in 2006–2007. Through an analysis of the historical layers of, and community response to, the crisis, the paper aims to provide insight into how lived memories of occupation, war and resistance form part of the East-Timorese community in the present day. Hedda Haugen Askland is an anthropologist currently working in the School of Architecture and Built Environment at The University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia. Hedda conducted the research for her PhD thesis in 2006 and 2007, at a time of political conflict and national upheaval in East Timor. Her PhD pays particular attention to how the political conflict manifests within the East-Timorese community in Australia and how communal and national memories are negotiated in the shadow of political conflict. Thushara Dibley is an Honorary Associate at the University of Sydney and a Visiting Scholar at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. Her PhD focussed on how ideas about peace-building were exchanged and developed in the partnerships between local and international NGOs in East Timor and Aceh, Indonesia. Before starting her PhD, Thushara lived and worked for a local NGO in East Timor in the lead up to and during the 2006 political crisis. Richard Butler The Orkney and Shetland Islands comprise the northernmost extent of the British Isles, and as such have always held an important strategic position in times of European conflict. Both island groups possess a widely varying heritage of conflicts over a period of a thousand years. This heritage takes many forms, physical and intangible, visible and hidden, recent and ancient, personal and materialistic. Many examples have become tourist attractions, almost irrespective of the nature of the feature involved, while others have been virtually ignored, important perhaps only to those with a personal attachment. The paper places the major warrelated heritage features of the islands in the context of a continuum of attitudes toward war heritage developed by Butler and Suntikul (2012). The related discussion then turns to the way in which warscapes of these islands have been transformed into memoryscapes (JansenVerbeke and George 2012) in certain situations but remained warscapes in others. The role of the war legacy in Orkney and Shetland and its sustainability is reviewed in the context of the present tourism image of the islands and their marketing as tourist destinations. Butler, R.W. and Suntikul, W. (2012) Tourism and War, Routledge: London Jansen-Verbeke, M. and George, W. (2012) ‘Reflections on the Great War centenary: from warscapes to memoryscapes in 100 years’, in Butler, R.W. and Suntikul, W. (eds.) Tourism and War, pp.273-287. Routledge: London Richard Butler was educated at Nottingham University (BA Hons in Geography) and the University of Glasgow (PhD in Geography), and then spent thirty years at the University of Western Ontario in Canada where he was Professor and Chairman of the Department of Geography. After returning to the UK in 1967 he spent eight years at the University of Surrey as Deputy Head (Research) and Professor of Tourism in the School of Management. He then moved to Scotland and took a part-time position as Professor of International Tourism at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, and is now Emeritus Professor in the Strathclyde Business School. He has published many journal articles, sixteen books on tourism and many chapters in other books. His research interests include the development of tourist destinations, the impacts of tourism, carrying capacity and sustainability, and tourism in remote areas and islands. He is a past president of the International Academy for the Study of Tourism and the Canadian Association of Leisure Studies. His recent books include Giants of Tourism, dealing with the role of individuals in changing the face of tourism, Island Tourism: Sustainble Perspectives, Tourism and Political Change, and most recently, Tourism and War, published in August 2012. Gilly Carr What dictates how long an island will hang on to its memory of war? How long after war do certain marginalised memories begin to be narrated and articulated by heritage? Does the inward-looking or seemingly isolated nature of islands mean that memory narratives take longer to play out than those of the nearby mainland which had similar experiences? Or do some islands deliberately nurse memories which run counter to that of the outside world as part of their strategy of insularity and independence? And why should a traumatic experience be incorporated into the identity of an island and still worn as a badge of pride 70 years later? This paper explores these issues through the lens of the British Channel Islands, whose memories and heritage of the German occupation of WWII have now become an obsession – at least in the two largest islands of Jersey and Guernsey. Occupation nostalgia currently has the upper hand in the heritage of these two islands. Not even the return of the traumatic ghosts of war, both literal and metaphorical, have had the power to topple this most dominant of memory narratives which has reigned supreme since the late 1970s. Gilly Carr is a Senior Lecturer and Academic Director in Archaeology at the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Continuing Education. She is also a Fellow and Director of Studies in Archaeology and Anthropology at St Catharine’s College. Her fieldwork is based in the Channel Islands, where she has worked and published extensively on the archaeology, heritage and memory of the German occupation. Her latest book, Legacies of Occupation: archaeology, heritage and memory in the Channel Islands, is forthcoming. She also works with former deportees who were sent to German internment camps during WWII. Her museum exhibition, Occupied Behind Barbed Wire, was on display in Guernsey and Jersey Museums in 2010 and 2012 respectively. Joseph Cheer The historical meaning of the Battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands during 19421943 is that Theodore Roosevelt regarded it as the turning point of the Pacific War. However the enduring significance for Melanesia is that the material and intangible cultural heritage of World War Two related sites remain throughout the region over seventy years later. The war related cultural heritage situated throughout the Solomon Islands and to lesser extents Papua New Guinea, Fiji and Vanuatu (formerly the New Hebrides) remain unexamined and little known (notwithstanding the influential work of Geoffrey White and Lamont Lindstrom). There is also an enduring intangible heritage associated with the Second World War driven in large part by what Marianne Hirsch has termed postmemory that in Melanesia largely constitute familial memories of Islander communities. Perhaps the most obvious of these in a Melanesian context are the World War Two related patrilineal cargo cults of Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea. Yet less obvious examples of intangible heritage can be found amongst a number of Melanesian communities in the present day. In this paper we discuss the long-term legacy issues associated with the memory of war throughout Melanesia. In doing so we consider how long-term desires for present day historical settlements remain and are directly related with heritage and human rights as well as questions of wartime restitution that still resonate today. We also contextualise the implications of increased pilgrimages to key heritage sites associated with the conflict including, for instance, travellers walking the Kokoda Track in Papua New Guinea. Taking the key conference question of what can we learn from these islands of memory we interrogate how the interplay between war memory, heritage, history and regional policy interact in ways that present challenges for creating a cohesive regional framework and relations with neighbours in the present. These include the contention that rather than leading to a lasting peace, the Pacific War exacerbated longstanding internal tensions in parts of Melanesian society particularly in the Solomon Islands. Accordingly we argue that diverse war heritage issues such as cargo cults, the management and interpretation of key war sites, the memory of the war, the impact of pilgrimages to former South West Pacific theatre of war battlefields and more recent state building interventions such as the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI) are all part of a broader suite of present day heritage issues. Issues that are best understood in the context of the desire of many Melanesians, their respective governments and also regional stakeholders for a greater awareness and respect of Melanesian cultural heritage. Joseph Cheer is currently Associate Director of the Australia & International Tourism Research Unit (AITRU) at the National Centre for Australia Studies (NCAS), Monash University. Joseph maintains an abiding research interest in the Melanesian countries of the Southwest Pacific, (especially Vanuatu, Fiji and the Solomon Islands) having lived, worked and travelled throughout the region. His research interests are focused on development, livelihoods, tradition, transformation, cultural change, postcolonial legacies and, in particular, the impacts of tourism expansion in the small island states of the South Pacific. Alexander Debono Malta’s war legacy stands against a culture and identity backdrop. Geographic proximity to Italy decisively influenced Malta’s cultural identity. British counter measures to align culture and identity to the politics of Empire were oftentimes perceived to be heavy-handed and certainly uncalled for by pro-italian elites. Language and later heritage thus became contested values leading to a drastic outcome. Pro-Italian elites, vociferously critical of British colonial politics, were transferred to Uganda. Others, mostly those studying at Italian art academies, handed in their British passports to the authorities on the outbreak of hostilities. This was understood by the British to be nothing short of treason and the outcome, irrespective of whether these emanated from the authorities or self-imposed, is still a matter of debate. This paper will discuss post war cultural narratives then still tainted with pro-Italian sentiment. It will explore the impact of World War Two on the islands, then perceived to still be a safe haven from the pressure of change, and the ways in which culture stands as a backdrop to these contested memories for particular social groups. Sandro Debono read art history at the University of Malta and is currently Senior Curator at the National Museum of Fine Arts (Malta). Research interests include cultural policy, collections management and the socio-historical relativity of art and artistic expression. He has also researched core-periphery issues and the migration of aesthetic ideas, iconographies and stylistic trends. Sandro is currently reading for his doctorate on heritage policy and collections development at University College (London). He has been active in the Maltese heritage sector for over twelve years. Beate Feldmann Eellend Islands are symbols of both pleasure and danger. Their function in surveillance and defence has influenced people’s daily lives for decades. I have chosen to focus on some arenas connected with threats and unease in the Baltic Sea Area — Gotland, Rügen, and Saaremaa. Large areas of land on these islands were cordoned off for long periods because of military activity, and it was only after the end of the Cold War that they became available for foreign visitors — when the islands’ geographical location in the center of the Baltic Sea no longer represented a military-strategic borderland. Few studies have examined the civil-military physical and cultural interaction in the military landscape. The aim of my study is to investigate how spatial practices are shaped in and also shape garrison towns both in aspects of urban planning and architecture of military places and of everyday relations within them. Furthermore, it examines the presence, or rather the absence, of collective memories in conversion planning documents on both EU macroregional (Baltic Sea Region) and local level of the post-military landscape. The ongoing military conversion process implies a troublesome cultural and physical transformation in different spatial scales. Islands are usually described as attractive tourist paradises with their coasts and nature. Yet, former garrison towns with their Cold War remains in the post-military landscape are seldom valued as attractive and re-useable. Rather, a kind of cultural amnesia appears in the findings of my study. Beate Feldmann Eellend is a PhD student in Ethnology at the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies at Södertörn University /Stockholm University. She is working on physical and cultural transformations of the urban landscape, mainly from a heritage perspective. Brent Fortenberry and Andrew Baylay At the dawn of the 20th century, South Africa was embroiled in a conflict between the British Empire at the height of its power against the Orange Free State and the South African Republic. The Second Boer War was fought between 1899 and 1902 and claimed tens of thousands of lives on both sides. The British were in need of POW camps and decided to build one on the British Empire’s stronghold of the western Atlantic, Bermuda. Bermuda is a mere 50 square kilometres and in 1900 had a population of only 17,000. The Second Boer War which was being fought 7,000 miles away temporarily increased Bermuda’s population by a third and forever changed the landscape and lives of Bermudians. An industry evolved where the POWs would carve intricate cedar items and sell them to Bermudians who would sell them to (primarily American) tourists. To this day, Boer carvings are cherished family heirlooms and much sought after auction items. In September 2011 the Bermuda National Trust surveyed the Boer War Cemetery, which was used to bury POWs who died whilst in Bermuda and is viewed as the epicentre of Boer War memories in Bermuda. In this paper we explore the Boer’s early 20th century material landscape of memory and also how their presence lingers in 21st century Bermuda. Andrew Baylay was born and raised in Bermuda. He gained a MA in Maritime Archaeology and History at Bristol University in 2005. He is currently an archivist at the Bermuda Archives. Also he is the chairman of the Bermuda National Trusts Archaeological Committee, which is an entirely volunteer group. Brent Fortenberry is Lecturer in Archaeology at Boston University and Archaeological and Heritage consultant for the Bermuda National Trust. He completed his PhD in 2012 at Boston University. Since 2007, he has partnered with the Bermuda National Trust for archaeological work at a variety of sites across the island. His new project explores the archaeological memories of Bermuda's role in the Boer War. Robert van Ginkel During the German occupation, the island of Texel (the Netherlands) seemed to be escaping from the war nearly unscathed. While the nearby naval base of Den Helder endured many German and allied air strikes, Texel was of little strategic importance, even though it constituted part of the German’s Atlantic Wall. The island had been occupied without fierce hostilities and major damage; the islanders and the occupiers tacitly agreed on maintaining cordial but distanced relations; the resistance movement was but small and persecution of Jews was largely invisible once the two Jewish families on the island had been forced to leave in 1941. By the spring of 1945, it was abundantly clear that the war was nearing its end in Europe. Many parts of the Netherlands had already been liberated from September 1944 onwards, and the islanders were anxiously awaiting their turn. However, Texel unexpectedly turned into a major battlefield. A German infantry battalion consisting of Georgian ‘volunteers’ had been stationed there in February 1945. On April 5, these ‘Russians’ – as the Texelians dubbed them – rose up against the German military. Fierce fights ensued, resulting in many Georgian, German and civilian casualties. This episode and its heritage, remembrance and commemoration are replete with disagreements, ambivalences and revisions, particularly at local level. This paper will focus on Texel’s post-war memorial and commemorative trajectories and how memorialisation is embedded in and influenced by national discourses and global geopolitics. Rob van Ginkel is a senior lecturer in cultural anthropology at the University of Amsterdam’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology. He has done extensive field research on the island of Texel from 1989-1991 and 2005-2006, while also being a resident there from 20062011. His most recent research project concerns the commemoration of the Second World War in the Netherlands, which resulted in a book entitled Rondom de stilte. Herdenkingscultuur in Nederland – Around the Silence. Commemorative Culture in the Netherlands (2011). Marek Jasinski On the 22nd of July 2011 the small island of Utøya became one of two places of the biggest national trauma in Norway since the World Word II. After exploding a huge car bomb in the governmental quarter in Oslo, the single right-wing terrorist got on the island of Utøya and subsequently open fire at the participants of annual summer camp organized by the AUF, the youth division of the ruling Norwegian Labour Party, killing 69 and injuring at least 110. Already the following day, the leader of AUF (Arbeidernes Ungdomsfylking – the youth organisation of the Labour Party) declared their intention to “take Utøya back”, rebuild it, expand its infrastructure and make it even more charming then it was before. Soon after, this declaration created a serious schism within the AUF, among survivors, families of the killed and in the entire nation. By today, the majority seems to agree with this intention, which means that Utøya, as it is now, can soon be lost. However, a quite active and growing minority argues that the island and all its structures should be preserved in the present state and become a national memorial of the 22.07.2011 attack. This paper presents several important aspects of the on-going process and exposes how narratives, memories and material heritage are formed immediately after traumatic events. Utøya serves here as a case study for the often very decisive early stages of such processes and can be used further as a comparative perspective for other sites of trauma and terror of modern times. Marek E. Jasinski is Professor of Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology and Studies of Religion at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. His main research interests have been Mediaeval and Post-Medieval Archaeology of the European Arctic; Maritime Archaeology; and Conflict Archaeology. He has been leader and Norwegian co-leader of several major research projects in Norway, Russia, Greece, Argentina, Mexico, United Arab Emirates and Bulgaria. During the last three years he has been leading the interdisciplinary project ‘Painful Heritage: Cultural landscapes of the Second World War in Norway. Phenomenology, Lessons and Management Systems.’ He is the author and co-author of approximately 200 publications. Ian M.P. Kinane Since the initial 'opening up' of the Pacific Ocean to the west, by explorers such as Cook and Bougainville, the islands of the south seas have long been viewed as timeless paradises, abstractions of quotidian time, that persevere in the cultural imagination as sites of old world naturalism, ostensibly unmarred by interventionism. Following the outbreak of the Second World War, however, the cultural history of the Pacific had to be re-written. It was on the island of Guadalcanal, of course, that the allied forces first began to gain ground on the Japanese army, which led eventually to their victory in the Pacific. The Islands of Palau, a small Micronesian island nation, saw some of the fiercest battles of the war. In this paper, I want to examine how precisely this 'theatre of war' has been recaptured in the popular American reality television show, Survivor, the tenth season of which was filmed within and around the islands of Peliliu and Koror, those most affected during the war. Filmed in 2005 - some fifty or so years following the end of the war - Survivor: Palau, I will suggest, can be read as a memorialisation of the trauma that occurred. Survivor, which pits two opposing teams or 'tribes' against each other, in what is often compared to as a 'battle' or 'war', is a veritable re-mapping of the war experience, I will argue, played out for the benefit of popular entertainment. Utilising Pierre Nora's theories of 'Lieux de Mémoire', I want to suggest that Survivor: Palau re-posits the cultural memories of war within the very 'theatre' in which they were first 'performed'. I want to examine how exactly the memory of war is constructed within the show, and to suggest that the re-enactment of this cultural memory is predicated on narratives of purgation and guilt. Ian Michael Philip Kinane has completed his M.Phil in Popular Literature at Trinity College Dublin, and is now reading for a PhD in the representation of Pacific desert islands in popular 20th and 21st Century literature and film. Irene Lagani Cythera, known from antiquity and the Homeric epics as the birthplace of the goddess Aphrodite, was in the West connected with a dream-like, distant place where Love and eternal peace reigned supreme. This image inspired western painters, writers, and even musicians. But this idyllic image does not in the least correspond to the island’s history during WWII. Although Cythera did not follow the history of mainland Greece as a part of the Ionian Islands, during the War it offered a representative example of all that occurred in mainland Greece: resistance, collaboration, civil war and then, oblivion and silence would put their stamp on the history of this period. Thus, although Cythera was the first part of Greece to be liberated by the German withdrawal (4/9/44), and the first place where the English army disembarked (11/9/44), the first anniversary of Cythera’s liberation would not be celebrated for half a century. Testimony by surviving Cythereans even today brings to the surface wounds that have not healed, a reconciliation that was not achieved, and a history that has never been taught in schools. Irene Lagani has a doctorate in History from the University of Paris I, Pantheon-Sorbonne. She is Professor in European History at the University of Macedonia (Thessalonica). Her research interests and publications are in the field of Cold War, inter- ethnic relations in the Balkans, and refugees of the Greek civil war. Sheila Lecoeur The Cyclades islands were occupied by the Italians (May 1941) until the Italian Armistice (September 1943) and under German control until November 1944. The Italians had a de facto colony in the Dodecanese (since 1912) and they sought to create an Italian Empire based on Rhodes. Their policy included extracting food and minerals from the Cyclades for the benefit of Italy. Due to the war and Italian requisitioning, there followed a severe famine, particularly in industrial centres such as Syros. While Red Cross relief eventually reached the mainland (Autumn 1942), most of the islands were cut off by the war and only received substantial aid from 1945. This paper will examine memories of the occupation and how they are perceived and expressed in the present. For many Greeks the subject was regarded as taboo because it appears to reveal national weakness and does not fit in with the official, patriotic narrative. On islands like Syros, with a Catholic and Orthodox community, there are contradictions in collective memory regarding the Italian and German occupiers, collaboration and ‘prostitution’ and the death rate, recorded on local monuments. While memories of the devastating famine on the mainland have been superseded by the traumatic experience of civil war from 1946-9, the islands were less involved and survivors retain clear memories of this traumatic time. Local research throws light on how the occupation functioned on a daily basis and the islanders’ personal experience is an essential added dimension to extensive primary research. Sheila Lecoeur (BA Hons, University of Westminster, 1976; MA, LSE, 1987;PhD Birkbeck College, 2005) has taught Italian and Italian cultural studies at the University of Westminster (1978-1990) and Italian and French and Translation at Imperial College (1990-2012). Her research interests include: Fascism and women, the socio-economic impact of occupation on Greece, in World War II and location research and filming for a documentary on memories of occupation and famine in Greece, 1941-5,‘Famine and Survival in Greece, 1941-5’ December 2012. Her publications include Mussolini’s Greek Island. IBTauris,(2009). Kris Liaugminas Following the end of World War II, the Marshall Islands in Micronesia came under the governance and administration of the United States, who owned and operated the archipelago as a U.S. Strategic Trust Territory of the Pacific from 1947 to 1986. Between 1946 and 1959, the United States proceeded to detonate 67 nuclear weapons on various atolls in the Marshall Islands during the formative years of the Cold War, moving the native islanders out of their homes on the affected islands and onto resettlement camps on other islands, while causing increased rates of cancer and birth defects for future generations of Marshall Islanders. Using a variety of actual testimonies, government documents, and the remote Marshallese literature produced during this time, this paper will explore the effects of this nuclear testing within the Cold War context of the U.S. military policy of containment, on a remote island chain deemed so small and “contained” that U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger stated in 1969: “There are only 90,000 people out there. Who gives a damn?” Faultlines within the political rhetoric by the United States government and the aftermath of its nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands will be examined, focusing on the impact of this testing on the health, legacy, and future cultural practices for the Marshallese people. Kris Liaugminas is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Arts, Law and Education and the University of the South Pacific, Suva. Federico Lorenz In 1982, Argentina and Great Britain fought a brief war over the sovereignty of the Malvinas / Falklands Islands. Two island communities were mainly affected: those of the Falklands (where most of the fighting took place) and that of the island of Tierra del Fuego, nicknamed during the war the “aircraft carrier island”. In 1982 residents of Fuegian cities revived military preparations dating from 1978, when Argentina and Chile were close to war over the Beagle Channel. The inhabitants of the Malvinas/ Falklands faced the war as the Argentine "occupation" that they had always feared. On both sides, even if islanders wanted to forget the war, it wouldn´t be easy. They live precisely in the places where the events took place. Anniversaries moved outsiders (tourists, ex soldiers) to revisit old battlefields, cemeteries (in Malvinas), airfields, ports (in Tierra del Fuego) and local museums (in both places). Many of these spaces have become monuments and sites of memory for pilgrimages and state commemorations. Between April and June each year, those small communities face peaceful “memory invasions”. The war of 1982 was a turning point for identities in both sides: In Malvinas, it was the year of liberation; in Tierra del Fuego, of defeat and loss. Every year islanders has to deal with those visits that question as well as strengthen their memories of the war This paper compares war memories of islanders, both Malvinas/ Falklands and Fuegians as displayed in recollections, memory sites and the activities held around them. Focusing on peculiarities, our exploration seeks also for common ground between them. What are the elements common to the Argentine and British islanders memories of the war of 1982? Does their insular character give greater strength to them? Is it possible then to think of a “Southern war memory”, different from their respective “national” ones? Federico Lorenz, is a historian and researcher based at Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas – National Council for Scientific and Technological Research, and is Argentina’s leading historical expert on the Malvinas. He has published Las Guerras por Malvinas (2006, new edition 2012), Fantasmas de Malvinas: Un libro de viajes (2008), and Malvinas: Una guerra argentina (2009). His novel Montoneros o la Ballena Blanca was published by Tusquets in April 2012. Elena Mamoulaki Ikaria is one of the many Aegean Islands that were used as places of internal exile for political detainees during the Greek Civil War (1946-1949). More than 12,000 left-wing political detainees were deported by the government to Ikaria, (which at that point had less than 10,000 inhabitants), without any provisions for housing, medical care and sometimes even food supplies. On the island there were no prisons or camps to host the exiles that were thrown helpless, under guard, to the isle’s shores. What makes the case of Ikaria special is that in the midst of an ardent civil war between the rightists and the leftists, the great majority of Ikarians of varying political orientations warmly welcomed the exiles providing them both material and moral support and thus, saved their lives. This case stands in vivid contrast to the dominant narrative of the civil war: not only were people not killing each other, but the exiles’ and Ikarian ethos was able to transform the exile penalty into a fruitful symbiosis. In this paper I will focus on the formation of memory through the interpersonal relationships among Ikarian, former exiles and their respective descendants as well as on the conflicts and dilemmas in the process of the institutionalization of the exile’s memory as a cultural and historical heritage of the island. Elena Mamoulaki is a lecturer at the Arcadia University in Athens. She was visiting Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (20072009). She held a grant from I. Latsis Foundation in Greece (2008) and the Ministry of Education in Spain (2006-2007). She is currently a PhD candidate in Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Barcelona. Her thesis is titled ‘An unexpected hospitality: narratives, practices and materialities of the memory of exile and cohabitation on the island of Ikaria. Nota Pantzou Greece is a country of 6000 islands, islets and skerries, whose modern history is marked by transnational wars and civil conflicts, making it an ideal backdrop for investigating the impact of war and politics on small island communities. Considering the country’s long island tradition and the prominence of islandscapes in tourist imagery and national narrative, the present paper proposes to discuss current local and national attitudes to island conflict heritage and the prospects of war tourism. Using a combination of sources and findings, attention is drawn to the Aegean exile islands. This preliminary study of the contested tangible and intangible heritage of political internment will reveal whether insularity affects its sustainability and the intensity of conflict memories in such remote and peripheral contexts. Nota Pantzou received her undergraduate degree in Archaeology and History of Art from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and her postgraduate degree in Archaeological Heritage Management and Museums from Cambridge University. In 2009 she completed her doctorate in Archaeology at University of Southampton. Nota’s research interests include Archaeological Heritage and Museum Management with a focus on local communities, Contemporary Archaeology, Traumatic Heritage and Socio-politics of the Past. She currently teaches in the MA in Heritage Management (University of Kent/Athens University of Business and Economics). Hazal Papuccular The Dodecanese Islands, despite their smallness, constitute a strategic point within the Eastern Mediterranean both vis-à-vis the Asia Minor/Dardanelles and vis-à-vis the Middle East. This strategic importance of the islands, which were under the Italian sovereignty in the interwar years, caused them to be part of the Second World War too. In addition to their use as a bargaining tool, especially within the relations between Turkey and the Allies from 1939 until 1943, they became a real scene of battle in 1943 between German and British forces. After the battle, in which Britain was defeated, these islands were occupied by the Nazis and remained under the German occupation until 1945, in which the German troops were exchanged with the British ones. The war, especially the phase after the German occupation, reserves an important place both in the history of the Dodecanese and in the memories of the islanders. In this respect, this paper while looking into the general history of the war on the basis of the Dodecanese Islands, will try to shed light on some aspects of the war that occupy the memories of the islanders even today. In addition to the hunger, which has been touched upon even in Turkish novels and underlined by archival sources, the migration of Greek, Italian, and Turkish people into Asia Minor and the large refugee issue shaped the post-war attitudes of people and the states that were interested in the region. These aspects also show the vulnerability of the islands in terms of their isolation as well as their need for the mainland in the time of crises. Even today, the war museum in Leros and the memorial of the Dodecanesian Jews’ extermination in Rhodes keep the memories of the war in the islands alive and this paper will try to analyze some of these aspects within the framework of the Second World War history in the Dodecanese. Hazal Papuccular has an undergraduate degree in Political Science and International Relations, and an MA degree in Modern Turkish History. She is a PhD candidate at Bogazici University in Istanbul, Turkey, in the department of Modern Turkish History. She is now writing her dissertation on the Dodecanese Islands with the title of “War or Peace? Dodecanese Islands in Turkish Foreign and Security Policy, 1923-1947.” Her research interests are in Turkish Foreign Policy, 20th century European History, and Aegean Sea Studies. Her publications include Turkish-Italian Relations in the Interwar Period: Italian Mare Nostrum Policy and the Formulation of Turkish Foreign Policy in Response (2010). Linda Riddell Shetland’s geographical location was an integral component of its history, way-of-life and identity. This paper investigates the interaction between geographical position and community identity in the context of the World Wars in Shetland and addresses how, although, obviously, the geographical position did not change, the experience and commemoration of the two wars was, and is, different. Although perceived as peripheral, in the Great War, Shetland, the most northerly part of the United Kingdom, was of strategic importance as a potential location for a German invasion and the most convenient harbour for the blockade of Germany and provided the base for a variety of naval activities. In a unique situation, the loyalty of the Islanders was distrusted, particularly in the Admiralty, based on their Norse past and links to Germany. In addition to the prevailing strains of wartime, civilians were affected by martial law, disruption to the economy and difficulties with transport. The paper will analyse how, particularly in the local newspapers, war was related to the local community identity, as well as to solidarity with the nation and Empire, and why the perception developed that the Islands had made disproportionate sacrifices. This idea was reflected in the production of over fifty memorials and is still prevalent today. In World War II, the threat of invasion was much more real and servicemen were again stationed in Shetland, but, as in most rural areas, civilians escaped the worst of enemy action. With memorials already existing, commemoration was more low-key. Unusually, today the most active commemoration is for the men of another country: Shetland was the base for the ‘Shetland Bus’, the Norwegian resistance operation, reviving historic links. This paper questions to what extent Shetland’s circumstances in and memories of war-time, despite having unusual features, had aspects in common with those of other island groups. It explores how the geographical location, isolation and perceptions of remoteness of islands influence community identity and links to the wider nation and other countries and contribute to how the wars were experienced and memories constructed. Linda Riddell was born in Shetland and lived there for most of her life. After retiring from a career in the oil industry, she studied for a MSc in Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh and has recently completed a PhD on 'Shetland and the Great War'. Stephen A Royle In 1982 the Falkland Islands were thrust onto centre stage through an anachronistic colonial war. A complex political history left both the UK and Argentina claiming sovereignty, although the British had held possession since 1833. Largely for domestic political reasons, Argentina invaded the Islas Malvinas; for similar reasons, the UK recaptured them weeks later. Since then the Falkland Islands have been transformed; the economy is now dominated by fishing not wool; tourism has grown, there is oil offshore. Yet 1982 is not forgotten: associated tourism is important, from veterans, relatives and thano-tourists; that the British had to recapture the islands means that their leaving now is inconceivable, to the satisfaction of islanders. That was not the case before 1982. Landscapes remain scarred, wreckage of crashed planes remain, although some battle sites have been sanitised by memorialisation. Mental scars remain, too. Those who were there have stories, not always told to strangers. Their attitudes towards Argentina have not softened; attitudes shared by their children. The forthcoming referendum seeking local views on sovereignty will produce an result worthy of a dictatorship’s ‘election’, but the result will not be rigged; no need. The paper will deal briefly with the campaign and its aftermath; opine about what is in the nature of islands and these islands in particular that retains the power of 1982 and look to the future, in which 1982 will play a significant role. Stephen Royle is Professor of Island Geography at Queen's University Belfast. His researches have taken him from the islands off Ireland to islands all over the world. There is some focus on those caught up in British colonial activity such as St Helena, Vancouver Island, the Falkland Islands and islands then called Port Hamilton off Korea. He is a Member of the Royal Irish Academy. Jonathan Sweet The Kelabit Highlands in the heart of Borneo are traditional lands of the indigenous Kelabit people. In 1944, ‘Z Special Force’ member, Major Tom Harrisson (anthropologist, archaeologist and a member of Mass Observation) parachuted into the Plain of Bah, where, from the village of Bario he organized and led the Kelabit people in a campaign against the Japanese.1 The isolated tropical highlands of Borneo became part of the theatre of modern warfare. The memories of the events of WWII are still with the Kelabit people, vividly manifested in intergenerational stories shared within a vulnerable and fractured community. As the elders with knowledge of life before and during WWII pass away, there is a strong desire to document Kelabit history and heritage and to articulate the meaning of the landscape that is central to their culture. This is seen as essential for the preservation of identity and for the representation of values to visitors, real and virtual. This paper will discuss the current debates and projects that are being undertaken to document and prioritize the heritage of the Kelabit people. It will consider how the decisions being made by an isolated community are being shaped by the influences of the past, the perceived rewards of cultural tourism and the availability of affordable communication technologies. The account is based on source material drawn from archival research and from fieldwork, during which the author has worked directly with the Kelabit community.2 Dr Jonathan Sweet a Senior Lecturer at Deakin University, Australia. He is a member of the Cultural Heritage Centre for Asia and the Pacific. His work in recent years has focused on heritage and development issues in South East Asia. He has published in the journal South East Asia Research and has contributed case study chapters to the forthcoming books: the Handbook of Research on Religion and Development, Edward Elgar, and the Oxford Public History Handbook. Daniel Travers This paper discusses the legacy of Orkney’s involvement with the HMS Royal Oak disaster and its Italian POWs. Brought to build infrastructure in the islands, the Italians left a tangible legacy of their presence on Orkney’s physical and mnemonic landscape. Orcadians give pride of place to their association with Italian POWs in a way that no other place in the British Isles does. The Churchill Barriers, now used as causeways which connect the island, and the Italian Chapel, an ornate Roman Catholic chapel built by the prisoners, provide the impetus for this positive remembrance. The Italian connection has been allowed to permeate even the most fundamental of Orkney’s cultural displays, such as centuries old traditions and festivals. This stands in direct contrast with traditional ‘British’ remembrance which tends to minimize 1 Between 1946 and 1960, Harrisson worked for the preservation of the indigenous tribes of Borneo as the Curator of the Sarawak Museum, Kuching, and visited Bario often and collected material from the region. His account of his wartime experiences, World Within: A Borneo Story, was published in 1959. 2 See, Jonathan Sweet and Toyah Horman, ‘Museum development and cross-cultural learning in the Kelbabit Highlands, Borneo’, Museums Australia Magazine, Vol.21 (1), Museums Australia, Canberra, August 2012, pp.23-26. AT: http://www.museumsaustralia.org.au/site/mam_current.php the POW contribution to the war effort in favour of highlighting British workmanship and resolve. I argue that Orcadians highlight their involvement with this aspect of the war experience in order to project themselves as more than just a northern Scottish county. Much like their long-term association with Norway, the Italian connection forged during the Second World War has now become a way to differentiate themselves from Britain and reinforce their own ‘national’ identity Daniel Travers is currently Adjunct Professor of History at Laurentian University in Canada. Specialising in how the identity of island societies can be shaped in relation to historical and cultural association with Britain, Daniel was awarded his PhD with Vice-Chancellor’s distinction from the University of Huddersfield in May 2012. He is the author of published articles on the memory of war in Jersey, Orkney, and the Isle of Man, and was co-editor (with Jodie Matthews) of Islands and Britishness: A Global Perspective, published by Cambridge Scholars in February 2012. David Watters The Caribbean region is rarely taken into consideration with respect to World War II. It was a minor theatre of operations, situated within the Western Hemisphere, and experienced limited combat actions, all of which conspired to render an appraisal of the region as being of little concern or, at worst, as insignificant in the world-wide scope of the war. This somewhat dismissive external perspective contrasts markedly with views held by many persons within the Caribbean region, where World War II is seen as having had significant impact in the economic, social, and political realms. This paper argues that the Caribbean, including insular and continental areas, was strategically important to a degree rarely appreciated, with the conflict differentially affecting the peoples of the region’s sovereign nations and the French, British, Dutch, and American colonial possessions. This encompasses as well persons from the Caribbean who served in overseas military and civilian locales. Memories of the war in the Vichy French islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe differ from memories on British islands, especially those affected by construction of American military and naval facilities and the presence of “occupation troops”. While wartime installations rarely survive, memories do persist among Caribbean populations to this day. David R. Watters was a Caribbean archaeologist for thirty years before his retirement from Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 2010. He was appointed Curator Emeritus upon retirement. His research included prehistoric and historical archaeology, especially in the Lesser Antilles. For the past ten years he has actively researched World War II in the Caribbean, drawing together perspectives from persons external to the region who served there and citizens of the broader Caribbean who worked within the region and in overseas venues. Geoffrey White World War II in the Pacific Islands region was profoundly transformative. Histories of the region commonly assert that the war disrupted static colonial regimes and propelled island communities toward independence. For island nations, postwar and postcolonial commemorative histories are often constructed in concert with Allied narratives of liberation that cast islanders as loyal wartime heroes. This paper, drawing on several years of ethnographic and historical research in the Solomon Islands, will argue that liberation narratives have consistently overwritten other histories of resistance to colonial authorities and even collaboration with Japanese that emerge when one listens more closely to the diversity and range of indigenous voices. The paper presents a case study of one islander’s renarration of his experiences as one of the famed “coastwatchers.” His retelling shifts the prism of war historiography in a way that turns a narrative of heroic battle with Japanese invaders into a story of personal and localized struggle against the violence of colonialism. Geoffrey White is a professor of anthropology at the University of Hawaii. From the 1980s to the present he has been working on indigenous memories of World War II in the Pacific; American memories of Pearl Harbor at the national memorial and, more recently, American tourism of D-Day memorial sites. Relevant publications include The Pacific Theater: Island Memories of World War II (co-edited), Black and White Memories of the Pacific War (coauthored), and Perilous Memories: The Asia Pacific War(s) (co-edited).