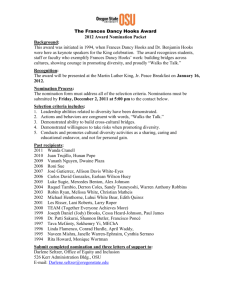

Reasons and Beliefs

advertisement

Reasons and Beliefs Abstract The present paper identifies a potential challenge for a popular view of practical reasons, according to which practical reasons are states of affairs. The view has been defended most forcefully by Jonathan Dancy, and the paper consequently focuses specifically on Dancy’s claims on the issue. The challenge consists of the fact that Dancy seems forced to maintain both a) that the contents of beliefs are states of affairs and b) that the view according to which the contents of beliefs are states of affairs is outlandish. The suggestion is put forward that, by distinguishing the content of a belief (as a proposition) from its object (as a state of affairs), the conflict between a) and b) can be neutralised. Since our proposal assumes only the basics of Dancy’s theory of reasons, it is available to all those theorists who share his conviction that practical reasons are states of affairs and are ready to embrace the object/content distinction. Even though the paper introduces an argument that is not, in the end, found decisive, awareness of the argument and of the related dialectics appears indispensable to all those wishing to further the discussion of Dancy’s views and of the ontology of practical reasons more generally. I. Against Dancy’s theory of reasons: the argument A fundamental feature of human beings is their being agents, and their invoking reasons as grounds for their actions. But what is it, exactly, that we refer to when we appeal to such reasons? That is, what kind of things are reasons for action? There are three main views on the ontology of practical reasons (henceforth ‘reasons’, unless a qualifier will be needed to avoid confusion): that they are mental states, that they are non-mental states of affairs, and that they are propositions.1 Here, our focus will be on the The notion of a ‘state of affairs’ is less straightforward than is desirable, primarily because it does not correspond to a unique, shared definition. Additionally, and relatedly, it is intertwined with the equally ambiguous notion of a ‘fact’. For instance, it is often held that facts are states of affairs that obtain, while in other cases ‘fact’ and ‘state of affairs’ are considered synonyms (indeed, Dancy uses the two concepts quite flexibly and interchangeably). Here, we will assume that states of affairs are logical complexes constituted by objects, properties exemplified by those objects and/or relations between those objects. We will also assume that there are states of affairs corresponding to universal generalisations, and that conjunctive, disjunctive and negative facts are mere logical constructions out of more basic facts - nothing will hinge on this particular choice in what follows. Last but not least, we will assume that states of affairs may or may not obtain, i.e., be part of the actual world. 1 1 second of these views – we’ll call it ‘statism’.2 Among those who endorse statism, Jonathan Dancy enjoys a prominent position, partly because of the innovativeness of his argumentation, and partly because of the extremeness of his position. Dancy argues (especially in his book Practical Reality) that that there is only one notion of a ‘reason’, which we use to answer two questions: one having to do with motivation (why someone acted in a particular way) and one with normativity (whether there was a good reason to act).3 In particular, Dancy’s arguments are geared to ultimately lend support to his claim that both normative reasons and motivating reasons are states of affairs. Although statism, and Dancy’s version of statism in particular, is by no means a universally shared philosophical view, little can be found in the literature as far as an explicit discussion of the view is concerned (for exceptions, see Everson (2009) and Lord (2008)). In this paper, we plan to add to this marginal critical literature by presenting and assessing an argument that might represent a potential challenge to Dancy’s theory of practical reasons.4 Although we will ultimately come to the view that Dancy’s position can be defended against the proposed objection, this is by no means tantamount to claiming that the position should be given preference over the others. Nor does it make the present paper a sterile philosophical exercise. To the contrary, our discussion here is intended as a way to introduce some crucial qualifications in the debate, thus hopefully preparing the ground for a more focused critical assessment of Dancy’s position (a first attempt at which we offer in our (blinded reference)) as well as of statism and the ontology of practical reasons more generally. Here’s the argument against (Dancy’s version of) statism that we wish to discuss. 2 Turri (2009; 491-492) provides extensive bibliography for each of the three positions (he focuses on epistemic reasons, but the literature is in large part the same for practical reasons). What we call ‘statism’ he calls ‘factualism’. 3 For a clear statement, see Dancy (2000; 2-3, 99). 4 The key idea is perhaps essentially the same as in Lord (2008), or maybe there is just an analogy between the argument to be presented here and Lord’s. Since we are unsure as to the correct interpretation of Lord’s claims, we will just mention this here and move on with our discussion. 2 Dancy holds that:5 1. Practical reasons (both motivating and normative) are what we believe (99, 101). 2. What we believe are things that can be expressed using that-clauses (107, 121). 3. Things that can be expressed using that-clauses are the contents of beliefs (113, 147-8). Therefore: 4. Dancy must hold that motivating and normative reasons are the contents of beliefs. However, it is also the case that: 5. According to Dancy, normative reasons are states of affairs (not propositions, mental states or some other alternative) (115-7). 6. According to Dancy, motivating and normative reasons belong to the same ontological category (2, 99). Therefore (from 4-6): 7. At least insofar as they constitute practical (motivating and normative) reasons, Dancy must hold that the contents of beliefs are states of affairs. However: 8. Dancy argues that the view that the contents of beliefs are states of affairs is outlandish (117-8). Therefore, and this is the core of the objection (from 7-8): 9. Dancy has to endorse a view that is outlandish by his own standards.6 For simplicity’s sake, we will call the argument formalised in 1-9 above the Outlandishness Objection (OO) from now on. 5 Bracketed page references in the argument are to Dancy (2000). Dancy appears to realize, especially in section 2 of Chapter 7 of his (2000), that there is something wrong with the overall coherence of his position. He nonetheless refrains from explicitly dealing with the issue. 6 3 Is OO compelling? Premises 2 and 3 appear to be convincing, and the same can be said with respect to premise 8 - at least for the sake of the present discussion.7 Therefore, it seems that OO can only be avoided by Dancy by giving up either his practical realism by, e.g., dropping statism (premise 5), or the unity of reasons assumption (premise 6). However, these are the very cornerstones of Dancy’s thinking about reasons, so abandoning them in order to avoid endorsing an allegedly outlandish independent thesis does not seem advisable. In what follows, rather than inferring the defeat of Dancy’s statism from the above, we will present an alternative way out for statists: that of resisting the conclusion by having recourse to a distinction the acceptance of which makes OO unsound. A note before we proceed. One might want to question the relevance of OO by pointing out that we misinterpret Dancy’s views as they appear in the premises of the argument. Although we are fairly confident that our interpretation is correct, we would like to emphasize that exegesis is not our primary aim in this article. Instead, we offer OO as an objection to any statist who holds premises 1-3 and 5-6 – a bundle of views that give us, what we take to be, an important strand of statism. Note, furthermore, that even if our exegesis of Dancy’s views is mistaken, it still remains the question what then Dancy indeed thinks about these matters. One can thus also read the upcoming discussion as offering alternative views as candidate accounts of what Dancy thinks about the ontology of reasons.8 II. The content/objection distinction Let us get back to the main issue. Our claim is this: the anti-statist conclusion above does not follow if a key distinction is made explicit between the content of a belief and its object. The latter is often confused with the former, and many even take content and object to be obviously identical. But this is a mistake. In fact, the view that the content and the object of a 7 8 The problem with false beliefs that leads Dancy to this conclusion will be discussed in detail in section IV. Dancy clearly holds premises 1, 5, 6, so what can be disputed as a matter of exegesis are premises 2 and 3. 4 belief are to be kept distinct has a good historical pedigree. It dates back at least to Gottlob Frege and, more specifically, Franz Brentano, who both urged philosophers to inquire into the nature of the intentional connotation of a lot of our thinking, i.e., of the fact that our minds can represent, be about things ‘out there’ in the world. Edmund Husserl famously elaborated upon Brentano’s insights, claiming that the essential property of being directed onto something does depend on the existence of some physical 'target', but only in virtue of the relevant intentional act.9 The content/object distinction also has its authoritative defenders nowadays. According to Tim Crane (2001a), (2001b), for instance, we need both object and content in order to characterise a subject’s perspective on the world. As he puts it: “Directedness on an object alone is not enough because there are many ways a mind can be directed on the same intentional object. And aspectual shape alone cannot define intentionality, since an aspect is by definition the aspect under which an intentional object (the object of thought) is presented” (Crane 2001a; 29). The necessity of intentional contents (in Crane’s terminology, ‘aspectual shapes’) in addition to objects is illustrated by Crane on the basis of an example: “When you think of St. Petersburg as St. Petersburg, the aspectual shape of your thought is different from when you think about St. Petersburg as Leningrad, or when you think of it while listening to Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony” (Ib.; 19). 9 See also Twardowski’s On the Content and Object of Presentations (1977, originally 1894), where the thesis is put forward that in every mental act a content (‘Inhalt’) and an object (‘Gegenstand’) must be distinguished. According to Twardowski, every mental phenomenon is directed towards its object, but not towards its content. See Moran (2000) on Brentano, Husserl, Twardowski and Heidegger. See also Prior (1971) and Stout (1918) for further uses of the content/object distinction. 5 That is, although the intentional object, namely St. Petersburg, is the same in all three thoughts, it is represented in three different ways, thereby being associated with three different intentional contents. As for the claim concerning the need for objects in addition to intentional contents, the point is the following: since we are dealing with the way an object is presented to a subject having an intentional attitude, the existence of an intentional content/aspectual shape presupposes that of an object the subject enters in relation with. It could be contended already at this point that, as it is conveyed by the above St. Petersburg example, the object/content distinction is not instrumental to Dancy’s purposes, for it points to objects, and not states of affairs, as the fundamental entities in the world. However, it is sufficient for statists to say that objects are indeed the basic entities, but they are always provided with certain properties. And since states of affairs are always analysable in terms of objects, properties and relations (see footnote 1 above), the alleged ‘ontological gap’ is easily filled. Relatedly, one could protest that the statist has to argue that, exactly like objects, states of affairs can be presented under different aspectual shapes, and this is implausible. The idea is that St. Petersburg can be thought of as Leningrad, but also as what Shostakovich’s symphony indirectly refers to: in these and analogous cases, there seems to be no ambiguity as to what the relevant object in the world is. However, it doesn’t seem equally clear that, say, the state of affairs of London being the largest city in the UK is the same as the state of affairs of the seat of government being the largest city in the UK. But if this is the case, the needed uniqueness of objects corresponding to multiple contents is lost. If there is a problem at all here, however, the statist can solve it by simply making the plausible claim that a criterion of identity for states of affairs should be employed that is exclusively based on sameness of objective, actually possessed properties and relations. In the above example, the 6 state of affairs of London being the largest city in the UK is in fact, according to such a criterion, the same as the state of affairs of the seat of government being the largest city in the UK. On a slightly different note, one might even accept the criticism, while at the same time pointing out that, since the intentional element grounding the object/content distinction is never put into doubt by the objection under consideration, the defence of Dancy’s statism being proposed remains intact. III. Neglected possibilities (and one winner) Having said this, let us get back to the main issue. Once the object/content distinction is in place 10 , premise 1 of OO can be straightforwardly rejected by pointing out that practical reasons (both motivating and normative) are not what we believe but what our beliefs are about: that is, they are not the contents of beliefs but their objects. Since the objects of beliefs are best understood as states of affairs, this entails that a way opens to save Dancy’s statism: i.e., that of identifying practical reasons (both motivating and normative) with states of affairs in such a way that the problematic conclusion 9 of OO no longer follows. Here is a pictorial illustration of what we are suggesting (bold indicates the path taken, similarly for the rest of the figures in what follows): Content/object distinction What we believe Propositions What our reasons are about States of affairs Reasons Figure 1. First possible view. 10 At least as something we have decent reasons for regarding as correct: as we will explain later, it is not necessary for statists to provide conclusive arguments in favour of the distinction. 7 At one point, Dancy himself comes close to this idea, but an important difference remains. He says the following (Dancy (ms), probably an earlier version of his (2009); italics added): “Application of this distinction between content and object to the case of belief is more contentious, because we are used to thinking of the proposition that stands as the content of belief also as the ‘what is believed’, that is, as the object of belief. My own (heretical) view about this is that we should stick to our guns, and announce, contrary to established philosophical practice, that a proposition cannot be believed; when I believe that p, what I believe is a putative state of affairs, something capable of being the case but not of being true.”11 From the quoted passage it is clear that the ‘new’ Dancy (as compared to his 2000 counterpart) endorses the content/object distinction with the corresponding metaphysics (the contents of beliefs are propositions, while their objects are states of affairs), but also thinks that reasons are what we believe, which he identifies with the objects of our beliefs (contrary to premise 3 of OO). The following figure illustrates this, and the difference with respect to the previous proposal: Content/object distinction Reasons What we believe Contents of beliefs Propositions Objects of beliefs States of affairs Figure 2. Second possible view. The qualification ‘putative’ is needed here in order to take care of the possibility of false beliefs, i.e., of reasons not corresponding to actual state of affairs. We will discuss this scenario in the next section. 11 8 This is no doubt a strange idea, however. For it is agreed here that what we believe are things that are expressible via that-clauses (as premise 2 of OO says), and these are normally taken to be propositions, not states of affairs. Indeed, as we already pointed out, premise 3 is normally assumed to be true, perhaps even obviously so. To insist that reasons are what we believe, and yet should be identified with states of affairs, then, is certainly an idiosyncratic view that requires an explicit argument. However, Dancy does not provide such an argument. The same would be true were Dancy to give up premise 2 of OO: since this thesis is very plausible, the burden of proof would be on Dancy to provide an alternative account, which, again, he doesn’t do. Given that the less contentious alternative that we sketched at the beginning of the section is available, we therefore conclude that this second option doesn’t appear worth pursuing any further. But there is more to say. With a view to making sense of both the nature of that-clauses and the statist claim that propositions - traditionally understood - cannot be reasons, one could point out that there are really two kinds of propositions. Namely, on the one hand, what one may call ‘Russellian propositions’, which are entities built up out of objects, properties, and relations; and, on the other hand, what one may call 'Fregean thoughts', or ‘Gedanken', which are entities corresponding to modes of presentation of those objects, properties, and relations.12 Using this idea, one could say that both the objects and the contents of beliefs are propositions: Fregean propositions in the latter case, Russellian propositions in the former. This might be regarded as a way of preserving the distinction between two different kinds of entities suggested by the content/object dichotomy, while at the same time explaining Dancy's claim above that "when I believe that p, what I believe is a putative state of affairs" without completely denying premise 3. For, premise 3 would still be true in the case that the things expressed using that-clauses are Fregean propositions, which are indeed the contents 12 George Bealer (1998), for instance, can be interpreted as having something like these two types of propositions in mind when he distinguishes between ‘connections’ and ‘thoughts’. 9 of beliefs. It would instead be false when the things expressed using that-clauses are Russellian propositions, i.e., the objects of our beliefs, what motivates our actions. In this latter case, moreover, there would also be a reason for accepting both premise 2 (what we believe is expressible via that-clauses) and Dancy’s claim that, when it comes to making sense of our actions, what we believe cannot be an abstract object in our minds. The view can be represented like this: Content/object distinction Reasons What we believe Two kinds of propositions Contents of beliefs Fregean propositions Objects of beliefs Russellian propositions Figure 3. Third possible view. This position, however, is clearly implausible: for, it crucially attributes an unstable ‘hybrid’ ontological status to Russellian propositions. Either Russellian propositions are sufficiently distinct from states of affairs for what we believe to be expressible via thatclauses, in which case statists cannot be happy with the view; or they are sufficiently analogous (identical, perhaps) to states of affairs to satisfy the statist, but then OO remains unanswered. A patent case of trying to have one’s cake and eat it too.13 13 Accidentally, Dancy (2000; 115-6) is clear that his view of propositions is much more Fregean than Russellian. (To be precise, Dancy mentions a third view, typically attributed to David Lewis (1986), according to which propositions are sets of possible worlds. However, for our purposes this account can be handled together with Frege’s view and does not require separate treatment.) Indeed, this is a view that he cannot easily give up, since the ontological nature of propositions plays a crucial role in his rejection of the view that normative practical reasons are propositions. We discuss this in our (blinded reference). 10 Essentially the same worry arises for a fourth and last view that we will consider here one that does not make use of the content/object distinction, but retains the distinction between Fregean and Russellian propositions. The idea is that reasons are what we believe, namely, the contents of our beliefs, which are entities expressible via that-clauses; and that these are propositions of two kinds: Fregean and Russellian. This means that beliefs can have two kinds of propositions as contents – Fregean and Russellian – and, consequently, practical reasons can also be tokens of these two kinds of entities. This position would thus accept premises 1-3 of OO, but would at the same time deny that conclusion 9 follows. Here is a schematic depiction: Two kinds of propositions Reasons What we believe Contents of beliefs Fregean propositions Russellian propositions Figure 4. Fourth possible view. This view, however, is hardly defensible. How can one argue for the idea that the contents of beliefs can be tokens of two different kinds of entities if not by making the ontological nature of practical reasons depend on context? If so, how are the relevant contexts to be identified and differentiated? It could be said that normative reasons are Russellian propositions, whereas motivating reasons are Fregean propositions (thus rejecting premise 6 of OO). However, this would mean to give up, contrary to what Dancy does and to our assumptions here, the unity of reasons. Alternatively, it could be said that reasons, both 11 normative and motivating, are Russellian propositions, except in those cases when the given states of affairs does not exist/does not obtain. However, this would still imply that in all ‘normal’ cases reasons can be either Fregean or Russellian propositions, thus reiterating the initial question. In addition to this, of course, the problem remains of what the relationship between Russellian propositions, Fregean propositions and states of affairs actually is and, consequently, of whether or not invoking such notions can truly save statism. The above discussion, we believe, has shown that the first proposed view, according to which a) the content and the object of our beliefs should be sharply distinguished and b) reasons are what our beliefs are about (the objects of beliefs), namely, states of affairs, is the best path to take for the statist. Before we move on to potential criticisms, an important element ought to be emphasised in order to avoid unnecessary objections. Our contention here was that, based on the fact that a distinction between the object and the content of a belief can be drawn and opponents of (Dancy-style) statism haven’t provided explicit reasons for rejecting it, Dancy’s view of practical reasons can be given a plausible formulation which doesn’t seem to fall prey of the OO objection. Albeit we did provide some limited support to the content/object distinction, at no point did we take a) above to be obviously true because grounded in an absolutely noncontentious metaphysical fact. This might be the case, but needn’t be so for the foregoing discussion to be of interest. To sum up, endorsing the content/object distinction can help the statist – at any rate, any statist who shares Dancy’s basic commitments – to avoid endorsing an outlandish view in the philosophy of mind.14 In particular, Dancy’s practical realism can be preserved, as well as his advocacy of the unity of reasons. 14 The statist will still have to struggle with corresponding problems in the philosophy of action, such as that of finding a role for belief in the explanation of action and that of answering the question what to do with false beliefs that seem to explain action. However, to these problems Dancy (2000; Ch. 6) does provide answers (to the first: the enabling and the appositional accounts of the role of beliefs; to the second: the idea of non-factive 12 IV. A problem with false beliefs? It might seem, however, that there is one outstanding problem for the solution to OO we have put forward. To illustrate it, let us begin somewhat afar: with the problem that, according to Dancy (2000: 117) himself, sinks the idea that the contents of beliefs are states of affairs. Here is an example proposed by Errol Lord (2008). John believes that his house is on fire and therefore calls the fire department. But the house is in fact not on fire, and thus the calling of the fire department was prompted by a false belief. Now, what is the content of John’s belief, given that the relevant state of affairs, the fire at John’s house, does not obtain? An extreme answer would be to claim that a false belief is a belief with no content. But of course this is not right: when we have a false belief, the latter does have a content, it is just that such a content does not ‘correspond’ to anything in the world - i.e., it is not matched by an object. In search for a way out, perhaps, one should follow Allan White (1972) in his suggestion that false beliefs (can) have non-obtaining content without having no content at all. Dancy (Ib.; 148-9), however, correctly worries that this option is insufficiently realist about true beliefs: if an existent but non-obtaining content is sufficient in some cases, on what basis should one insist on obtaining states of affairs in other cases – in particular, in the case of true beliefs? Moreover, and perhaps more tellingly, it is in fact problematic to understand what it means exactly for beliefs to have contents only in the non-ontologically-committing sense being suggested. As Crane (2001a; 33) eloquently puts it, although “there is a sense in which one may be thinking, and yet thinking about nothing, there is no sense in which one may be thinking, and yet thinking nothing.” Of course, there is an ambiguity here that one can get rid of by having recourse exactly to the content/object distinction that we have put our emphasis on in the foregoing. explanations). Although open to discussion, these are sufficiently worked out to allow the statist to continue pursuing the strategy being explored in the main text. These answers, moreover, seem to be compatible with the suggested content/object distinction as well as with OO itself. (We will have more to say on false beliefs in a moment, however). 13 The problem is, however, that the difficulty raised by Lord (and Dancy) seems to persist if one translates it in terms of objects, consequently constituting a threat for the proposal that we have put forward: What is the object of John’s belief, given that the relevant state of affairs, the fire at John’s house, does not obtain? More generally, do false beliefs have objects? It seems that they do not, since, as we just stated, their being false depends exactly on the fact that nothing in the world corresponds to their content. But then it looks as though the statist is forced to draw an ontological distinction between true beliefs and false beliefs, and to point at objects (i.e., states of affairs that obtain) rather than contents (i.e., propositions) as reasons only in the case of the former.15 In view of the foregoing, an immediate reply suggests itself: let us transpose White’s views into the claim that false beliefs do have contents (i.e., propositions), while it is their corresponding objects that can only be existentially quantified over in a non-ontologicallycommitting sense. Indeed, as the first half of Crane’s remark above also suggests, we can answer the question what our beliefs are about when asked, without this entailing the existence of something ‘out there’. For example, when asked, you can say that your (false) belief is about Pegasus or - although more controversially - about the round square, even though neither exists in the actual world. And the same is true of John’s belief in our example above: when asked, John can reply that his belief is about the fire at his house, although there is no fire at his house, as a matter of fact. Of course, there is a distinction to be drawn here between: i) in principle impossible objects (the round square); ii) objects that are not in the actual world (Pegasus); iii) objects that are in the actual world but do not have the properties we ascribe to them (the fire in John’s house). While it is essentially, if not exclusively, states of affairs involving type-iii) 15 Notice that this objection cannot be overcome by arguing for the reality of negative states of affairs (see, for instance, Barker and Jago (2012)). For, it is true that if negative states of affairs exist they can be the content of one’s beliefs. But believing that not-x is different from believing that x when x is not the case, and it is only the latter scenario that is relevant for the present discussion. 14 objects that are relevant for our present purposes, the general point that we are making concerns all three alternatives: in all these cases we can meaningfully say that ‘there is an x such that...’, and act accordingly, without thereby incurring inevitable ontological costs in terms of x, or the xs, existing in the actual world in a way that makes our existentially quantified statement true.16 More generally, since that of explaining the precise ontological nature of things that we can quantify over but do not take to be actual doesn’t exclusively pertain to the statists’ to-do list and is, instead, a shared task, the above remarks appear sufficient for circumventing the objection to statism based on false beliefs.17 An objection could be raised at this point analogous to Dancy’s objection to White: the view that is being put forward here is not sufficiently realist about true beliefs because, if it is enough for false beliefs to have objects in an ontologically non-committal sense, then it is not clear why true beliefs should have objects in a stronger sense. The obvious reply is that, whereas in the case of contents, since the alternative propositionalist account is available, the burden of proof lies on the statist, no such alternative exists in the case of objects. Indeed, what else could the object of a true belief be (in the case of practical reasons, at least) if not a state of affairs that obtains? Let us then assume that our proposed version of statism is internally coherent and can account for actions motivated by reasons corresponding to false beliefs. What are the consequences of this view in the philosophy of mind? A restricted form of internalism seems to follow. For insofar as they accept the thesis that the existence of a relation entails the existence of its relata, statists can and should deny that all thoughts are relations between 16 The qualification in italic takes care of the obvious objection that, in case iii), the relevant objects do exist in the actual world. This is true, but it is only certain states of affairs involving them, which nevertheless fail to obtain, that are relevant for us. 17 We take it that Crane’s (2001a; 13-8) somewhat obscure distinction between the schematic and the substantial is meant to capture essentially the intuition just presented in the main text. 15 objects that exist ‘out there’ and their thinkers.18 In particular, they should contend that, while true beliefs involve such relations, false beliefs may not. 19 This form of internalism is certainly a substantial specific view in the philosophy of mind. However, it is in general not considered outlandish by philosophers, and consequently represents an adequate tool for dealing with OO.20 V. Additional remarks Before ending our discussion, there are two other difficulties to consider. The first is that, contrary to what we claimed above (end of section III), the proposal being put forward might be taken to violate the unity of reasons assumption (premise 6 of OO) which, as noted, is one of the cornerstones of Dancy’s thinking. Isn’t it the case now that motivating reasons can be both obtaining and non-obtaining states of affairs, hence they are not the same thing as normative reasons, which can only be obtaining states of affairs? We don’t think this is a crucial objection. Dancy (2000; 101-105) supports the unity of reasons with the claim that any theory of reasons must meet what he calls the Explanatory Constraint (EC) – normative reasons must be capable of also playing the role of motivating reasons – and the Normative Constraint (NC) – motivating reasons must be able to function as normative reasons. Now, first, the view under consideration meets both constraints – as they, notice, do not require that every motivating reason also acts as normative (and vice versa). Secondly, and more importantly, the claim that intentional objects might be non18 Another option (Parsons (1980)) is to accept the possibility of relations involving Meinongian objects, i.e., objects that do not possess existence (Meinong (1960)). Alternatively, one could maintain, in the spirit of Frege (1960) and Russell (1904), that the objects of false beliefs exist, but not in the actual world – thus, presumably, in a Platonic way. 19 Whether all false beliefs are concerned depends on how strictly one understands the thesis about the existence of relations and relata. In particular, in case iii) above (objects that are in the actual world but do not have the properties we ascribe to them) one could consider the existence of the relevant objects sufficient for the holding of the relevant relations; but it is also possible to contend that, since no state of affairs obtains that corresponds as an object to the content of our beliefs, in that case too the relevant relations fail to hold. In this latter case,, all false beliefs would not be relations between thinkers and objects. 20 Incidentally, Crane is willing to embrace an even more radical internalism, extending the claims above to intentional attitudes towards actually existing objects. 16 obtaining states of affairs is not meant to introduce a new ontological category. All that follows from such a claim (when coupled to statism) is that whenever there in fact is both a normative and a motivating reason for a given action, they are identical - they are both obtaining states of affairs. This is sufficient for preserving the unity of reasons.21 The other putative difficulty has to do with an alternative theory of reasons that Dancy rejects: the so-called content-based approach. On this view, normative reasons are the contents of beliefs, while motivating reasons are beliefs with a content. This might now be turned into an ‘object-based approach’ on the basis of the content/object distinction: motivating reasons would then be beliefs with an object, while normative reasons would be the objects themselves (if any). One might argue that this approach can overcome the problems of the content-based version and, consequently, that the introduction of the content/object distinction weakens statism rather than lending support to it. However, this is not so. Dancy (2000; 114-9) argues that the content-based view faces a dilemma: if one holds that the contents of beliefs are propositions, one cannot maintain (premise 5 of OO) that normative reasons are states of affairs. If instead one holds that the contents of beliefs are states of affairs, one must endorse an outlandish view in the philosophy of mind. Now, in the context of the object-based approach just outlined one can claim both that the contents of beliefs are propositions and that normative reasons are states of affairs. Thus, one can indeed slip through the horns of the dilemma. However, it remains the case, as Dancy (Ib.; 113) argues, that the approach is unable to meet both EC and NC, so satisfying the unity of reasons requirement. For, motivating reasons will still be mental states, 21 A rejoinder could be that, if one adopts a Meinongian/Platonic stance, false beliefs involving non-obtaining states of affairs really do call specific ontological categories into play (say, non-existent but subsistent entities in Meinong’s sense, or Forms in Plato’s sense). If correct, this is, at best, a reason to insist on non-obtaining states of affairs that do not exist in any way in spite of the fact that we can talk about and quantify over them - which is, remember, our basic initial claim here. 17 consequently proving unable, given the assumption of practical realism, to act as normative reasons.22 VI. Summary In this paper, we have identified a possible, and so far neglected, attempt to refute the ‘statist’ theory of practical reasons, and in particular Jonathan Dancy’s version of it. Although we think that the objection is not fatal to Dancy’s views, we believe that it is important to be aware of it nevertheless. This is because, we take it, the analysis and discussion of it has larger repercussions for the debate on the ontology of reasons, insofar as it offers statists additional tools for defending their view. More generally, by critically assessing the objection, relevant differentiations and specifications seem to have been usefully added to the debate. Of course, on the one hand, one might wish to avoid the anti-statist criticism in some other way, perhaps not committed to the content/object distinction. Also, on the other hand, there might be other ways of arguing against statism, both in general and in the form of Dancy’s specific version of the view.23 But all this is material for future discussion. 22 Of course one might, in view of this, drop the unity of reason assumption. But, again, we are assuming that such an assumption represents an important motivation for endorsing statism. It certainly is an important, perhaps even fundamental, motivation within Dancy’s specific version of statism. 23 See, for instance, Mantel (2014) for a rejection of the unity of reasons. Lord (2008) argues instead against statism without directly attacking the unity of reasons assumption, and so do we in our (blinded reference), where in fact the unity of reasons is considered as a possible, important motivation for switching from statism to the alternative view that practical reasons are propositions. 18 References Barker, S. and Jago, M., (2012): “Being Positive About Negative States of Affairs”, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 85 (1): 117-138. Bealer, G. (1998): “Propositions”, Mind 107 (425): 1-32. Crane, T., (2001a): Elements of Mind: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Mind, Oxford: OUP. Crane, T., (2001b): “Intentional Objects”, Ratio XIV (4), 336-349. Dancy, J., (2000): Practical Reality, Oxford: OUP. Dancy, J., (2009): “Action, Content and Inference”, in Hans-Johann Glock and John Hyman (eds.), Wittgenstein and Analytic Philosophy: Essays for P.M.S. Hacker, Oxford: OUP, 278-298. Dancy, J., (ms): “Practical Reasoning and Inference”, URL: (http://experimentalphilosophy.typepad.com/2nd_annual_online_philoso/files/jonathan_danc y.pdf) (retrieved on 28/01/2013). Everson, S., (2009): “What Are Reasons for Action?”, in C. Sandis (ed.), New Essays in the Explanation of Action, London: Palgrave MacMillan, 22-48. Frege, G., (1960): “On Sense and Reference”, in Peter Geach and Max Black (eds.), Translations from the Philosophical Writings of Gottlob Frege, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 5679. Lewis, D., (1986): On the Plurality of Worlds, Oxford: Blackwell. Lord, E., (2008): “Dancy on Acting for the Right Reason”, Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, www.jesp.org, (September). Mantel, S., (2014): “No Reason for Identity: on the Relation between Motivating and Normative Reasons”, Philosophical Explorations 17 (1): 49-62. Meinong, A., (1960): “The Theory of Objects”, in Roderick Chisholm (ed.), Realism and the Background of Phenomenology, Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press, 76-118. Moran, D., (2000): Introduction to Phenomenology, London: Routledge. Parsons, T., (1980): Non-existent Objects. New Haven: Yale University Press. Prior, A.N., (1971): Objects of Thought, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Russell, B., (1904): “Meinong’s Theory of Complexes and Assumptions”, Mind 13 (50): 204-219. Stout, G.F., (1918): Analytic Psychology, London: George Allen and Unwin. Turri, J., (2009): “The Ontology of Epistemic Reasons”, Noûs 43 (3), 490-512. Twardowski, K., (1977): On the Content and Object of Presentations, Grossman, R. (transl.), Martinus Nijhoff: The Hague. White, A.R., (1972): “What We Believe”, in N. Rescher (ed.), Studies in the Philosophy of Mind, London: Blackwell, 69-84. 19