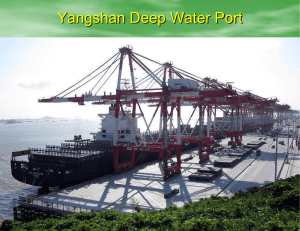

The applicability of competitive advantage theories to the port of

advertisement