Google ranked #1 on `Fortune`s` latest 100 Best Companies to Work

advertisement

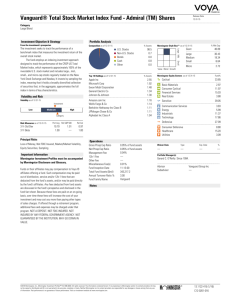

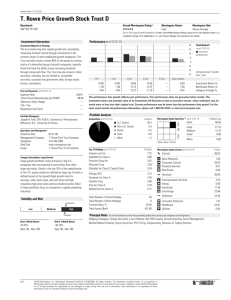

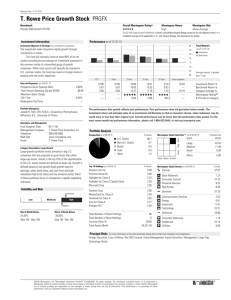

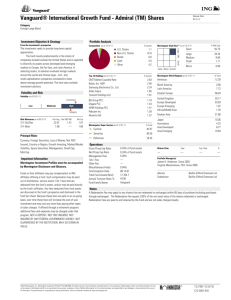

Do happy workers mean higher company profits? John Waggoner, USA TODAY9:15p.m. EST February 19, 2013 Maybe people don't want to be married to their jobs, but it seems to help if they're, to use a buzzword, "engaged." Google ranked #1 on 'Fortune's' latest 100 Best Companies to Work For list.(Photo: Tony Avelar, Bloomberg) Story Highlights There's good evidence that companies who treat employees well see their stocks prosper Employees who feel engaged and respected tend to do better jobs Low turnover means that good employees stay and are more productive Most people would like to believe that there's a kind of economic karma: Companies that treat employees well will see their stock prices rise, and those that treat employees badly watch their stocks fall. If only it were that simple. In theory, benevolent employers should have an advantage. "To me, it's absolutely true," says Jerome Dodson, manager of the Parnassus fund. "If a company treats its employees well, the business should prosper and that should show up in the stock price," Dodson says. It's a philosophy Dodson embraces in his own company. "When you have reduced employee turnover, it makes a huge difference in earnings," he says. "We don't need as many people, we don't have to hire headhunters, we're not continually retraining people." And, in fact, there's fairly solid evidence that companies that treat employees well see their stocks prosper. It's just that some companies that aren't noted as great workplaces can see their stock prices rise, too. The good guys Consider Google, nearly universally acclaimed as a great place to work. Its stock has soared 674% since its inception in August 2004. Google's offices abound with areas designed to promote interaction, from a bowling alley in Mountain View, Calif., to a pub lounge in Dublin, Ireland. The computer search company has a great health plan, a college reimbursement plan, legal aid, even travel assistance. Heck, if an employee dies, Google will continue to pay 50% of the deceased's salary to his or her family for a decade. Or consider Marriott, which offers employee discounts at its thousands of hotels worldwide. Work there 25 years, and you get free stays at the company's hotels and timeshares. Marriott has gained an average 11.3% a year for the past decade, vs. 7.9% for the Standard & Poor's 500stock index with dividends reinvested. The argument for companies that treat employees well, however, is not simply because people like to get benefits, although they do. "The data strongly support the fact that organizations that focus on the engagement of their employees deliver stronger performance," says Julie Gebauer, managing director for talent and rewards at Towers Watson. "It's not just making them happy — that's not a business issue. Engagement is." Employees who feel engaged tend to do better jobs and are more willing to put in the extra hours, Gebauer says. They also tend to stay at the company — and that, too, is a good thing, says Dodson. "There's all kinds of cost savings when there's low turnover," he says. At his company, 10-year employees become owners, and that, too, trickles down to the bottom line. "It motivates them to save us money," he says. Companies on Fortune's list of 100 Best Companies to Work For tend to have less employee turnover than average. In information technology, an industry notorious for job-hopping, voluntary turnover is 5.9% at the companies on the list, vs. 14.4% industrywide. In professional services, turnover in the best places to work is 11.3%, vs. 24.7% industrywide. Low turnover means that good employees stay and are more productive. The inverse is also true: Companies that have happy employees are less likely to have unhappy workplace events, such as strikes or class-action lawsuits — events that investors generally hate. Publicly traded companies in the Fortune 100 Best Companies to Work For list have gained an average 10.8% a year since 1998, according to the Russell Investment Group. Many of the publicly traded companies named as Best Companies to Work For in 2013 saw their stocks perform admirably last year: • Whole Foods soared 31%, vs. 13% for the S&P 500. • Marriott gained 28%. • American Express advanced 22%. Naturally, there were some disappointments, the most prominent of which was Chesapeake Energy, down 25% last year. Part of Chesapeake's problem was its continuing lavish perks for executives: Directors earned an average of more than $500,000 in 2011, according to the website Footnoted. Its CEO has earned notoriety for similarly lavish perks, including the company's $12.1 million purchase of his antique map collection in 2009. (The CEO later paid back the company, under pressure from shareholders.) Chicken or the egg? One big question, however, is whether companies that treat employees well do so because they are already successful and growing, and simply have the financial wherewithal to be generous. Google, for example, sits atop $48 billion in cash on its balance sheet; so does Cisco, another company on Fortune's list. Furthermore, some industries that were once known for generous treatment of employees, such as airlines and autos, did so for a long time — but that was when the companies were much more profitable than they are now. When a company is struggling, however, its first step is typically to start cutting employee perks, says Charles Bobrinskoy, manager of Ariel Focus fund. And that's typically seen as more humane than mass layoffs. You could also argue that companies in low-margin businesses — think grocery stores and fastfood chains — tend to have the least amount of money to spend making employees happy, and would therefore be least likely to show up on lists of great workplaces, much less great stocks. But Parnassus' Dodson disagrees. For example, his portfolio includes Costco but not Wal-Mart. "Costco pays their employees well and has good benefits," Dodson says. "They want people who are professional, not just quitting and going on to the next job." Costco has gained 30.5% the past 12 months, including reinvested dividends, according to Morningstar, the mutual fund trackers, vs. 19% for discount stores. And even in the beleaguered media industry, some companies still offer outstanding benefits. Morningstar, for example, gives employees a six-week paid sabbatical every four years. And employees are allowed to take as much vacation time as they need, says Bevin Desmond, president of international operations and global human resources at Morningstar. "It can be difficult for people to get used to," she says. "We hire people who are smart, motivated, aggressive and ambitious, and they put everything they can into the job." Having a good benefits package also makes the transition easier when Morningstar buys another company, Desmond says. "It tends to warm them up a bit to have a nicer medical plan." And, she says, Morningstar competes heavily with technology companies, which are noted for generous benefits. It pays off: Their chief technology officer came to Morningstar from Microsoft. But good employee treatment means more than a good dental plan, says Gebauer of Towers Watson. "What makes the biggest impact are things that don't have significant costs," she says. "How expensive is it for a senior leader to give an employee a pat on the back, or give someone the opportunity to work from home for a day or two?" The dark side While every company that treats employees well doesn't automatically outperform the S&P 500 in the stock market, those that habitually treat employees badly often do suffer for it — and for a long time. "Companies that have a poor reputation see a bit of a lag," says Linda-Eling Lee, executive director at MSCI. "And I do think that companies that lag — it's amazing that they chronically underperform. They lurch from crisis to crisis."