Law of Property

advertisement

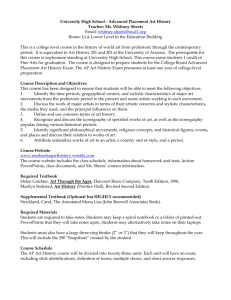

北京外国语大学法学院教学大纲 《财产法》 郑晓军 Law of Property Teacher: X. David Zheng Students: 2Ls, BFSU Law COURSE DESCRIPTION Introduction Property law, along with Torts and Contracts, is often said to be the backbone of the common law jurisprudence, a course offered in most U.S. law schools for the first year students. It is also, by all means, the fundamental ideology pillaring the social, economic and political systems of the common law countries. Take the English property regime, for example, which began to be formed at the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066. At its early stage, a feudal system, land was owned and passed from generation to generation in the form of life estates with the King sitting on top of the hierarchy, without vesting titles to those who lived and worked on it, i.e., without alienability. Gradually, because of the need to use land more efficiently, more permanent forms of land ownership appeared, and barriers to free transfer of land ownership were to be eliminated. This process, however, took four or five hundred years, through judicial reforms case by case, to be perfected as the property law we see today. The common law system, with the expansion of the British Empire all over the world, has been adopted throughout the English-speaking countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, India, Pakistan (and Hong Kong as well), with the property concepts as fundamental support for their political, social, economic, legal, philosophical, military, and foreign policy structures. What is amazing is that over the thousand years, political systems may be replaced, governments may change hands, and kings may be overthrown, but the continuity of the property system was never interrupted. The land property regime established under the English common law in the colonial states survived the Revolution even though the British control was severed, and even the English cases were adopted, as part of the common law, by the U.S. Constitution. Today, we may say, the English Empire is no more, but its legacy in the legal system is deep rooted in most countries of the world. This greatly deserves our close attention. We cannot but admire this unique, if not great, legal system (we may even call it philosophical), and definitely, we cannot go very far, without a thorough understanding of this system, learning the best of it, and using it to our benefit, as it has done to the rest of the world. Learning the Anglo-American property law has another great advantage: as it is taught completely in its original English language, your language ability will also be greatly improved as you go along by picking up the idiomatic terms and expressions unique in the legal studies. 1 北京外国语大学法学院教学大纲 《财产法》 郑晓军 That being said, property law is undoubtedly one of the most difficult courses in the common law studies, feared by most even in American law schools. This further requires us of greater efforts, more time and energy, in our studies as English is only our second language. The Case Method The course material is organized in the form of a collection of cases, abbreviated and edited to some extent, primarily because the “laws,” or the fundamental principles, exist in the form of judicial decisions. Some may call it the “unwritten” law, because unlike the continental European practices of giving it the form of black-letter statutes through legislative means. Ironically, the “unwritten” law requires more writing than the written law, and certainly, more reading and thinking, and rethinking, of the fundamentals in the studies. The case method, as we also use in our studies, was first used by Harvard Law School in the 1800’s, which requires that the students read the cases before coming to the class so that they understand the facts of the cases, think about the issues presented by the case, the decisions reached by the courts, and the principles established from the cases. Moreover, the students are also required to raise questions about everything they read, and be prepared to answer questions raised by the teacher, as if in the court arguing or defending the cases. Why is this so-called “Socratic” method in critical thinking important? Because, legal studies should not be about memorizing legal rules, which are the results of other people’s thinking; rather, the students ought to learn how these rules came about, and more importantly, how they applied to the facts of particular cases in reality to effectively solve our problems. The students need to “brief” every case they read. Since case-briefing is the topic for Legal Research and Legal Writing class, we cannot go beyond merely a brief description. A simple case brief should include: Facts Issue(s) What happened in this case with legally important facts, but not every detail that has no impact on the case; What is the central controversy, or what is the question(s) raised to the court for a solution Holding(s) How the court decided on (each) issue Reasoning Why the court decided this way, on what basis, with what consideration One thing has to be emphasized: because case briefing is the daily work for law students, there are some commercially prepared “Case Briefs” (some being even keyed to particular casebooks). They may both be available at bookstores or on the Internet. It has to be warned that you use these materials at your own risk, because the case-briefing process is your thinking process, and digesting process 2 北京外国语大学法学院教学大纲 《财产法》 郑晓军 of the study materials. When you use these ready-made materials, you are not thinking with your own brain, but merely swallowing what others have already digested. Course Materials All case materials used in this Course are actual cases decided in courts. Reading these cases is by no means easy because – as one legal scholar once explained – the judicial opinions were drafted for the courts, not designed as textbook materials for students. For this reason, the students need to be qualified for TEM IV at least. Each semester week a topic will be discussed, with case reading materials and questions presented in class. There are altogether fourteen topics. Class Evaluation A student’s achievement is evaluated by three criteria: class attendance, class participation, and a final examination. Class attendance simply means that every student is required to be present for class; no excuses will be allowed except for sickness of no more than three times. No other excuses will be allowed – not even for such extracurricular activities basketball matches, group singing, or other social events – for the simple reason that these activities are for the “extra” hours outside class. Merely being present for class is not enough; every student must come well-prepared for class discussion by reading the class materials beforehand. This is class participation which earns a percentage toward a student’s final score. Lastly, a tow-hour open book final exam is conducted at the end of the semester that makes up about 80% of a student’s final score. The student may bring the textbook, a dictionary and minimal amount of study aid materials. All exam questions will be entirely based on the textbook, and all exam questions are redesigned semester to semester. The exam includes three parts: True/False Questions, Multiple Choice Questions, and Essay Questions. Office Hour and Contact Information The teacher will be available for office hours to be announced during the first week of the semester. The teacher will also be available by email (xdavidzheng@gmail.com; xdavidzheng@bfsu.edu.cn) and by phone 186-1118-1368. 3