Mayer, et al.

advertisement

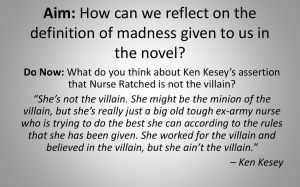

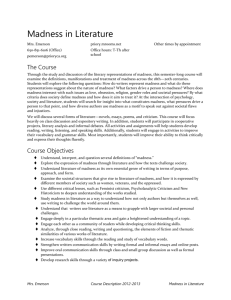

Mayer et al (2011) (Excerpts) Media representation within a discourse of gender and madness through Foucauldian theory What are the variables studied in the 5 texts that the authors examine? Examines five recent texts in media studies: Mediating Madness: Mental Distress and Cultural Representation (Cross, 2010); Madness, Power and the Media: Class, Gender and Race in Popular Images of Mental Distress (Harper, 2009); Reality Bites Back: The Troubling Truth about Guilty Pleasure TV (Pozner, 2010); Media Representations of Female Body Images in Women’s Magazines (Bale, 2008); and Bad Girls: Cultural Politics and Media Representations of Transgressive Women (Owen, Stein, & Vande Berg, 2007). What is the authors’ thesis ? The authors argue that media fixation on a rhetoric of women and girls in crisis contributes to our cultural discourse of madness and insanity. Why is madness constructed as feminine? Madness is constructed as feminine through media discourses that situate women’s behaviors in relationship to culturally constructed gender norms. As Foucault (1965) observes: Language is the first and last structure of madness, its constituent form; On language are based all the cycles in which madness articulates its nature. That the essence of madness can be ultimately defined in the simple structure of a discourse, does not reduce it to a purely psychological body; such discourse is both the silent language by which the mind speaks to itself in the truth proper to it, and the visible articulation in the movements of the body. (p. 100, emphasis in original) Why is ‘madness’ related to language? A discourse of madness is concerned with the language used to define madness, which contains psychological consequences for identity, and ultimately can be articulated through the body as illness, distress, or erratic behavior. Thus, media discourses situate women’s behaviors in relationship to culturally constructed gender norms. How did the ancient Greeks explain the development of madness? Traced back to ancient Greece where madness developed as a result of ‘‘overevaluation of male sexuality associated with male fear of mature female sexuality’’ as a result of dramatic age differences between marital partners. Why did clinicians link madness with sexrole? Diagnostic medicine developed, women’s madness was constructed through ‘‘assumptions about sex roles made by clinicians,’’ which often exhibit a ‘‘sex bias in judgments about social functioning’’ What variables play significant roles in identifying madness within cultural systems? Gender, sexuality, and power play significant roles in how madness is identified, articulated, and enacted within cultural systems. How do the authors link women and madness? Each of these authors link the representation of women in various mediated contexts to the problem of madness, which results in the manifestation of this ‘‘girls in crisis’’ narrative. How does the explanation of a mad person illustrate ‘Foucault’s conceptualization of the subject as constituting rather than constituted’? Foucault’s (1965) observation ‘‘on language are based all the cycles in which madness articulates its nature’’*shifting the language would simply shift the cultural normalizing function of discourse and reconstitute madness in similar, yet ‘‘new’’ terms (p. 100). This framing is distinctly gendered, as 1 madness is metaphorically and symbolically represented as feminine, even when experienced by men (p. 67). Thus, subjectivity is determined by the cultural process of coding madness, illustrating Foucault’s conceptualization of the subject as constituting rather than constituted How do narratives in movies gender differentiate discourse of madness? Using specific texts containing characters suffering from mental distress as evidence, Harper examines how different film genres engage a discourse of madness from a ‘‘fetishization of tragic femininity’’ (Sylvia, Iris, The Hours), which contrasts with the psychological enlightenment experienced by male characters suffering mental distress in biopics (Shine, A Beautiful Mind, Pollock) (p. 76). Even ambitious ‘‘madwomen’’ behaviors are seen as ‘‘therapeutically useful’’ as opposed to the ‘‘artistic strivings’’ of their ‘‘genius’’ male counterparts in dramas (p. 77), while female protagonists in comedies are generally seen as ‘‘not responsible’’ and ‘‘unable to take charge of their destiny’’ (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Bridget Jones’s Diary, House of Fools) (p. 84). According to Foucault (1965), madness is often culturally defined as ‘‘our blind surrender to our desires, our incapacity to control or to moderate our passions’’ (p. 85). The split in film is clear*men who surrender to their desires and passions become geniuses; women become subjects of their own self-destruction, eliciting at best pity and sympathy. Recognizing the limitations of film as a genre, Harper (2009) argues that television offers more diversity in the representation of mental distress, but that this in turn complicates the analysis of those images What are women’s magazines various sets of advice for its readers that would help them overcome ‘madness’? While magazines like Marie Claire, which offers a ‘‘Real Life Therapy’’ column every month (p. 162), often advise women that being content with one’s life is the key to mental health, they imply that gendered needs must be filled to overcome madness and offer ‘‘retail therapy’’ as a solution Women’s magazines are centered on mental health advice in conjunction with gendered demands of physical beauty (for instance, how Glamour magazine offers suggestions on how to energize your brain through shopping), the cultural assumption that women are ‘‘mad’’ by definition is reinforced The management of mental health, just like physical health, is most often constructed as an obligation of femininity, while mental distress is something that occurs in and is overcome by men How does ‘reality’ programs frame women? Pozner reveals how media frames women as irrational, helpless, and mentally distressed through reality programming, noting that the ‘‘reality’’ label allows these images to perpetuate a discourse of ‘‘real women acting badly.’’ In relation to Foucault’s (1965) observations on madness, the women succumb to their desire for heterosexual romance rendering their ensuing acts as subjectified to the humility that accompanies either rejection or conditional acceptance. The narrative emphasis on the ‘‘happy ending’’ creates a vision of women as fundamentally flawed, second-class citizens, capable of anything to secure the fantasy, which codes them for consumption as ‘‘mad’’ or ‘‘crazy.’’ What do the UG students found in the 12 magazines? In 2005, 99.3% of female body images in these 12 magazines viewed most by female undergraduate students were ‘‘thin.’’ This percentage suggests a connection between undergraduate women’s consumption of media, particularly women’s magazines and the development of body image dissatisfaction, ultimately becoming ‘‘an issue of life or death for some undergraduate women 2 How does F’s framing of madness explain the ways in which women are being treated in society? Through a Foucauldian frame, madness is ‘‘immediately perceived as difference: whence the forms of spontaneous and collective judgment sought, not from physicians, but from men of good sense’’ to determine the appropriate means of confining madness (Foucault, 1965, p. 116, emphasis added). Women are encouraged to establish self-constituting body politics that align with culturally acceptable standards of beauty, standards that confine the body into the smallest possible space. What was the experience of the sports reporter and how was it interpreted and explained? What would F call such an interpretation? Based on the actual experiences of sports reporter Lisa Olson, Sports Night’s reporter, Natalie, is the victim of attempted sexual assault during an interview that takes place in a men’s locker room during episode six. The authors explain this incident as a means of relegating women in journalistic fields to the ‘‘appropriate’’ rank of sexualized object rather than the suggested position as a critic of male performance through the transformation of the locker room as contested, gendered space. Natalie is seen as a cultural threat, tamed through the ‘‘hysterization of women’s bodies’’ as ‘‘saturated with sexuality’’ (Foucault, 1980, p. 104) How do the public imagines soldiering of the female, her body and gender identity? How would F interpret these films’ interpretations of soldering? The authors also deconstruct the coding of American female soldiers through films with Gulf War narratives such as G.I. Jane, Courage Under Fire, and The General’s Daughter. These films pose and answer questions about gender, the female body, and military combat. Women in these three films are viewed as ‘‘prey’’ in integrated military settings, their trustworthiness is debated, and double standards are often employed. Representations of women soldiers frame their bodies as strong but ultimately vulnerable. Linking back to Foucault’s (1965) observations about madness, the women always pay a price for their (mad) bodily transgression; some even face the ultimate price of death. By examining soldiering through the publicly imagined female body and gender identity, the authors conclude that in G.I. Jane ‘‘the female body is the primary problem that needs ‘solving’’’ 3