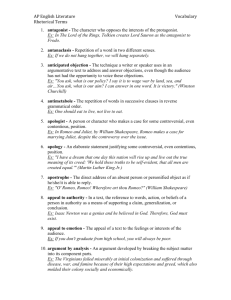

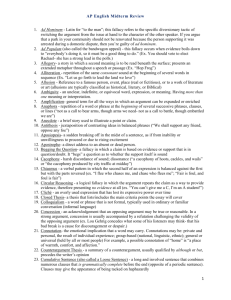

Rhetorical Strategies

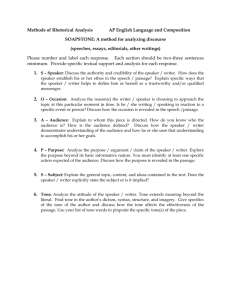

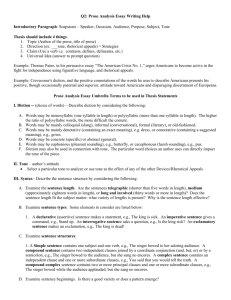

advertisement

AP LANGUAGE AND COMPOSITION/ENGLISH III, 2015-16 MS. LEAPHART Rhetorical Strategies Keys to Rhetorical Analysis (Remember the acronym WILDSTR) Word Choice (Diction): Diction refers to the writer/speaker’s choice of individual words. For example, a writer/speaker might use vocabulary that is colloquial (slang), conversational, technical, concrete, abstract, euphonious (pleasant sounding), cacophonous (harsh sounding), informal, formal, elevated, monosyllabic, polysyllabic etc. The words may have both denotative (literal) meanings and connotative (emotional/cultural) meanings that are important in context. Imagery: Imagery refers to appeals the writer/speaker makes to any of the five senses (sight, sound, taste, touch smell). Imagery is the term we use to talk about word groups coming together to create a “picture,” and it’s important to remember that it doesn’t have to refer only to visual imagery, but to other sensory imagery as well. Language/Literary Devices: The writer/speaker will likely use some forms of language/literary devices such as alliteration, assonance, consonance, onomatopoeia, simile, metaphor, hyperbole, understatement, paradoxes, oxymoron, personification, metonymy, pun, allusion, analogy, synesthesia, polysyndeton, asyndeton, and symbol. Remember that when you speak about language/literary devices, it is not enough to simply point them out; you must include an analysis of their effect. How does the writer/speaker use the particular device to reinforce his/her meaning or purpose? Detail: Details refer to the specific nouns (people, places and things/objects) or "facts" that the writer/speaker encodes in each passage. Keep in mind that often an author will intentionally omit certain objects or facets of the object for effect as well. Syntax: Syntax refers to the writer/speaker’s sentence structure. When discussing syntax, we talk about word order, sentence variety and types of sentences: A declarative (assertive) sentence makes a statement: The king is sick. An imperative sentence gives a command: Stand up. An interrogative sentence asks a question: Is the king sick? An exclamatory sentence makes an exclamation: The king is dead! A simple sentence contains one subject and one verb: The singer bowed to her adoring audience. A compound sentence contains two independent clauses joined by a coordinating conjunction (and, but, or nor, for, so, yet) or by a semicolon: The singer bowed to the audience, but she sang no encores. A complex sentence contains an independent clause and one or more subordinate clauses: You sad that you would tell the truth. Thanks to Geoff Proctor, HHS. AP LANGUAGE AND COMPOSITION/ENGLISH III, 2015-16 MS. LEAPHART Rhetorical Strategies A compound-complex sentence contains two or more principal clauses and one or more subordinate clauses: The singer bowed while the audience applauded, but she sang no encores. A loose/cumulative sentence makes sense if brought to a close before the actual ending: We reached Edmonton/that morning/after a turbulent flight/and some exciting experiences. A periodic sentence makes sense only when the end of the sentence is reached: That morning, after a turbulent flight and some exciting experiences, we reached Edmonton. In a balanced sentence, the phrases and clauses balance each other by virtue of their likeness of structure, meaning or length: He maketh me to lie down in green pastures; he leadeth me beside the still waters. In a natural sentence (in English) the order is subject + verb: Oranges grow in California. In an inverted sentence, the word order is somehow reversed to create an emphatic or rhythmic effect: In California, oranges grow. Juxtaposition is a poetic and rhetorical device in which normally unassociated ideas, words, or phrases are placed next to one antoher creating an effect of surprise and wit: "The apparition of these faces in the crowd:/Petals on a wet, black bough" (poem by Ezra Pound entitled "In a Station by the Metro") Parallel structure refers to a grammatical or structural similarity between sentences or parts of a sentence. It involves an arrangement of words, phrases, sentences and paragraphs so that elements of equal importance are equally developed and similarly phrased: He was walking, running and jumping for joy. Repetition is a device in which words, sounds, and ideas are used more than once to enhance rhythm and create emphasis: "...government of the people, by the people, for the people" (Lincoln's Gettysburg Addresss). A rhetorical question is a question that expects no answer. It is used to draw attention to a point that is generally stronger than a direct statement: If Mr. Smith is always fair, as you have said, why did he refuse to listen to Mrs. Baldwin's arguments? Punctuation is also included in conversations about Syntax o ellipsis (…) o dash (-) o semicolon (;) o colon (:) o italics (italics) o capitalization (ABC) o exclamation point (!) Thanks to Geoff Proctor, HHS. AP LANGUAGE AND COMPOSITION/ENGLISH III, 2015-16 MS. LEAPHART Rhetorical Strategies Tone: Tone refers to the writer/speaker’s attitude toward his or her subject, as well as the stylistic means by which a writer/speaker conveys his/her attitude(s). Tone is an integral part of a work's meaning because it controls the reader's response. In order to recognize tonal shift and to interpret complexities of tone, the audience must be able to make inferences base on active reading/listening. All of the rhetorical strategies listed so far work together to determine tone, but Word Choice (Diction) especially drives tone, so understanding an writer/speaker's tone requires understanding both the denotative and the connotative meanings of his/her words. The following may signal shifts in tone natural breaks and transition words like but, nevertheless, however, although etc. changes in line/sentence length paragraph breaks punctuation (dashes, periods, colons) sharp contrasts in diction Rhetorical Appeals: Keep in mind the three main ways a writer/speaker can appeal to his audience: by appealing to ethos (his/her own credibility), logos (reason & logic) and pathos (the audience’s emotions). Thanks to Geoff Proctor, HHS.