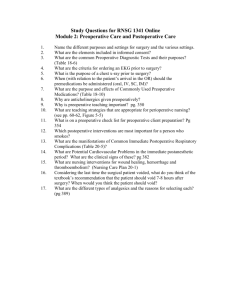

Aaron Hess AHEC Capstone February 2014 IS THIS A TEST

advertisement

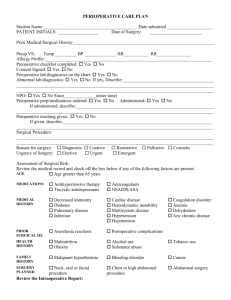

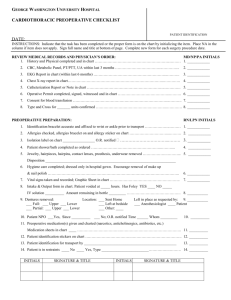

Aaron Hess AHEC Capstone February 2014 IS THIS A TEST? VALUE AND ROUTINE PREOPERATIVE TESTING A 65 year-old man with a history of hypertension and obesity presents to his primary care physician for a physical exam prior to a right total knee replacement. He has no personal or family history of cardiac disease, and other than dyspnea on exertion he has no suspicious symptoms. His physician orders a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, and glucose. He also obtains an ECG and gives the patient a referral for a chest X-ray. The ECG is unremarkable, and all labs are within normal limits. Three days later, the radiology report returns with a “radio-opaque mass” suspicious for a hiatal hernia. An upper GI series is recommended but does not find the mass, and the patient is scheduled for a CT scan the following week. The final CT report does not find any abnormalities. Two weeks later the patient undergoes surgery and is discharged from the hospital without complications. Physicians have an obligation to provide the best care for their patients, but with finite resources we also have to decide what tests are worth the money we spend on them. The Affordable Care Act will force hospitals to accept fixed payments for procedures, providing an additional incentive to only run tests that will significantly defray risk. Dozens of studies have shown that routine preoperative testing for low-risk surgery is rarely – if ever – indicated, and yet practicing physicians and trainees continue to order it. The reasons why may not just be about uncertainty over best practices, but of what patients, the law, and other physicians expect. This review will discuss data and opinion. In the first part, the history and current data on routine preoperative testing will be reviewed and discussed. Guidelines from medical societies will also be discussed. The second part will cover the experiences and opinions of physicians through research into the decision-making process behind preoperative testing. *** A search of the medical literature was conducted using MEDLINE MeSH terms “routine,” “preoperative,” and “testing”. 470 manuscripts were returned. Manuscripts were included for further consideration if they were 1) in English and 2) represented original research studies or 3) position statements or recommendations by professional societies. Studies of subspecialty populations, e.g., pediatric neurosurgery patients, were considered as long as they met other inclusion criteria. Additional manuscripts discovered in bibliographies that were not indexed in MEDLINE but met criteria were also included. *** The landmark paper demonstrating a lack of benefit to routine preoperative testing was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2000 by Oliver Schein and colleagues at Johns Hopkins(1). The Study of Medical Testing for Cataract Surgery showed that over 9,000 patients who underwent cataract surgery after routine preoperative testing did no better than a similar number of patients who only had testing as indicated by their medical history and physical exam. In their introduction, they point out that national guidelines endorsed “appropriate” testing, but made no effort to define what was appropriate or what data supported those statements. The investigators randomized 19,557 cataract operations in 18,189 patients across nine clinical centers to receive either routine preoperative testing or testing as indicated. Patients in the routine-testing arm gave a medical history and had physical exam, and then underwent a set of common preoperative tests, viz., an electrocardiogram (ECG), a complete blood count (CBC), and measurement of serum levels of electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), and glucose. Patients in the no-testing arm gave a medical history and had physical exam, and only underwent those tests that were indicated in the history. The primary outcome was a composite of death, hospital admission, or adverse event, e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke, oxygen desaturation, arrhythmia, etc. Several subgroup analyses were predefined, and rigorous data gathering procedures were observed. All analyses were by intention-to-treat. The result of the trial was that the rates of adverse events were identical in the two arms of the study: 31.3 per 1,000 operations (relative risk [RR] 1.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.9 – 1.2). None of the pre-specified subgroup analyses, including separation of intraoperative and post-operative events, revealed any statistically significant differences either. Of note, the majorities of events were intraoperative and judged by independent adjudicators to be related to the performance of the surgery, and not to underlying medical conditions. Participants in the two arms were well-balanced, although the authors noted that patients who declined to participate and were not enrolled tended to be older and were more likely to have an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) risk class of III or higher, i.e., they were more likely to have serious systemic disease. Significantly, the rates of surgical cancellation were nearly identical in the two groups, suggesting that the rate of events in the routine-testing arm was not biased by loss to follow-up. Schein and his colleagues recognized that the data they present had broad implications for all elective surgical procedures. Not only did patients randomized to routine preoperative testing fare no better that those who received only indicated tests, the authors could find no evidence that the results of those tests influenced preoperative or intraoperative management in any fashion. Moreover, 70% of the study population was over the age of 70 years, and 90% had at least one comorbid systemic illness. Although they are careful to point out that additional large randomized trials are needed to prove equivalence in sicker patients or those undergoing riskier surgeries, they recommend that routine preoperative testing be abandoned for low-risk surgeries. Prior to the Study of Medical Testing for Cataract Surgery, the most important clinical study of the value of preoperative testing was performed by Eric Kaplan and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco(2). The authors analyzed 2,785 randomly-selected laboratory tests ordered preoperatively on 2,000 patients admitted for routine surgery. Tests of interest included prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), CBC with or without differential, serum electrolytes, and BUN/Cr. Indications for each test were pre-specified. A trained reviewer examined each chart and determined if each test was indicated based on the results of the admission medical history and physical exam. Sixty percent of tests were not indicated by study criteria and only ten (0.36%) abnormal tests were found in patients without indication, of which only four were determined to be of surgical significance. In contrast, the rate of abnormal results among patients with indications was nearly nine times higher. Like Schien and colleagues after them, the investigators were not able to find any evidence that these apparently significant abnormalities resulted in any change in management. In their conclusion, they note that 9,000 tests and $95,800 (in 1985 dollars) could be saved each year at their hospital alone simply by ordering only those tests indicated. Several themes emerge from the research that followed Kaplan and Schein. A high proportion of preoperative tests are not clinically justified(3-5). The pretest probability of a positive result is vastly higher in patients with clinical indications for the test(3). When abnormal test results are found, whether the patient has indications or not, the results rarely appear to affect management(5-7). Many routinely ordered preoperative tests are neither sensitive nor specific in predicting perioperative complications or adverse events(8-11). Current data in support of routine preoperative testing is limited, and the practice is now supported only by opinion and the unease of physicians(12, 13). The 2012 update to the 2001 American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA) Practice Advisory for Preanesthesia Evaluation states: Preoperative tests should not be ordered routinely. Preoperative tests may be ordered, required, or performed on a selective basis for purposes of guiding or optimizing perioperative management. The indications for [perioperative] testing should be documented and based on information obtained from medical records, patient interview, physical examination, and type and invasiveness of the planned procedure(14). The Advisory goes on to detail a number of clinical tests that may be indicated based on the specific clinical circumstances, prefaced with a caveat: “there is insufficient evidence to identify explicit decision parameters or rules for ordering preoperative tests on the basis of specific clinical characteristics.” In the absence of clear data, it is up to the physician to judge what circumstances warrant a given preoperative test. ECGs may be indicated in patients with cardiovascular risk factors, but age alone is not an indication. Stress echocardiography is only indicated in patients with minimal exercise tolerance or those with intermediate exercise tolerance and intermediate cardiac risk, i.e., a Framingham 10-year risk of 5-20%(15). A chest x-ray should be considered in patients with recent history of respiratory infection or clinical suggestion of an ongoing thoracic process, but age, smoking, and stable COPD are not in and of themselves indications for radiographs. Blood tests such as CBC, serum electrolyte, and BUN/Cr should only be ordered in patients with a history of organ dysfunction where abnormalities on these tests may change management. Preoperative pregnancy screening has been hotly debated in the medical literature, but no good studies exist, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has not released guidelines on the subject, and the ASA does not recommend for or against testing(16). *** Why do physicians continue to order preoperative tests routinely? In the conclusion of their 1985 paper, Kaplan and colleagues make a back-of-the-envelope calculation about the potential cost in human life of abandoning all routine testing: […] the benefit-cost ratio is $4,170 per missed significant abnormality (95% lower bound, $1,570). In this time of fixed health care appropriations, finding a surgically significant abnormality may or may not be "worth" $4,170 (that depends, of course, on the consequences of the missed abnormality) but there may be a better way to spend those dollars to improve health care. For example, a conservative estimate of anesthetic mortality is 0.001 per operation. If lack of knowledge of a laboratory abnormality doubles this risk—certainly an inflated estimate—then the attributable risk (0.001) divides the benefit, to yield $4.2 million savings per additional life lost (assuming that all surgically significant abnormalities detected will be acted on, despite our empirical evidence to the contrary). Might $4.2 million spent some other way save more than one life?(2) In this remarkable passage, Kaplan appeals to the utilitarian philosophy “the greatest good for the greatest number” made famous by Jeremy Bentham and defended by John Stuart Mill in the book Utilitarianism (although Mill would argue, as Kaplan’s caveat seems to admit, that some forms of good were intrinsically more valuable than others). Kaplan’s point is sound: in a world of fixed resources and increased expectations, money being spent on results that are not of demonstrable benefit is money better spent elsewhere. In spite of 30 years of published data, recent literature suggests that physicians continue to order preoperative tests routinely, and that residents in relevant specialties are not trained to recognize indications for appropriate testing. In 1990 O’Connor and colleagues at San Francisco General Hospital reviewed preoperative testing before 486 elective pediatric surgeries, and found little utility but saw little need to stop because the test was “easy to obtain”(6). In 2012 Patey and colleagues published the results of a series of structured interview with eleven anesthesiologists and five surgeons on choices for routine testing. Among the results, anesthesiologists and surgeons noted that they frequently ordered tests not for known medical utility but in order to appease their colleagues(13). A survey of 354 anesthesiologists from 17 European countries noted that anesthesiologists ordered routine tests because they thought they were demanded by guidelines, but that they were in favor of reducing testing(12). Concern for patient safety was their major reservation. No published data exist on the attitudes of residents toward preoperative testing, or how they are trained to order preoperative tests. Intuition suggests that inexperience and caution would produce a bias towards excessive testing. A single study of anesthesiology residents, who might be expected to be well-versed in guidelines about preoperative testing, suggests that even when testing is complete residents did not know how to use the results(17). Vigoda and colleagues presented 548 US anesthesiology residents (approximately a quarter of the national total) with 5 scenarios about cardiac risk stratification of patients undergoing elective surgery. Less than half were able to appropriately identify which patients who required additional testing under current ASA guidelines. *** Based on the available literature, physicians continue to order routine preoperative testing because of poor communication and a lack of guidance. The current generation of residents is also not receiving training based in evidence – or in line with what will be expected under the Affordable Care Act. Unfortunately, it is also clear that much of the ambiguity in current practice stems from the size of the current literature. In light of these shortcomings, I propose five points for action: 1. Routine preoperative testing should not be ordered. 2. Research is needed to determine indications for preoperative tests and if there are sub-populations or surgeries for which certain tests should be ordered. 3. Major professional bodies including the ASA, American College of Surgeons, and the American Medical Association need to clarify existing indications for testing. 4. Academic medical centers and professional bodies need to lead the way in demanding improved communication between primary care physicians, anesthesiologists, and surgeons over testing for patients undergoing surgery. 5. More training is needed for residents in anesthesiology, surgery, and medicine in understanding the indications for preoperative testing. These are major goals, but they cover an important cause of medical waste and a major area of scientific equipoise. Together, they represent an opportunity for major medical reform for the benefit of all patients. *** References 1. Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, Tielsch JM, Lubomski LH, Feldman MA, et al. The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. study of medical testing for cataract surgery. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jan 20;342(3):168-75. 2. Kaplan EB, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann AJ, Roizen MF, Beal SL, Cohen SN, et al. The usefulness of preoperative laboratory screening. JAMA. 1985 Jun 28;253(24):3576-81. 3. Rohrer MJ, Michelotti MC, Nahrwold DL. A prospective evaluation of the efficacy of preoperative coagulation testing. Ann Surg. 1988 Nov;208(5):554-7. 4. Vogt AW, Henson LC. Unindicated preoperative testing: ASA physical status and financial implications. J Clin Anesth. 1997 Sep;9(6):437-41. 5. Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, Brown KM, Han Y, Townsend CM,Jr, et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg. 2012 Sep;256(3):518-28. 6. O'Connor ME, Drasner K. Preoperative laboratory testing of children undergoing elective surgery. Anesth Analg. 1990 Feb;70(2):176-80. 7. Aghajanian A, Grimes DA. Routine prothrombin time determination before elective gynecologic operations. Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Nov;78(5 Pt 1):837-9. 8. Dzankic S, Pastor D, Gonzalez C, Leung JM. The prevalence and predictive value of abnormal preoperative laboratory tests in elderly surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2001 Aug;93(2):301,8, 2nd contents page. 9. Jaroszewski DE, Huh J, Chu D, Malaisrie SC, Riffel AD, Gordon HS, et al. Utility of detailed preoperative cardiac testing and incidence of post-thoracotomy myocardial infarction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008 Mar;135(3):648-55. 10. Seicean A, Schiltz NK, Seicean S, Alan N, Neuhauser D, Weil RJ. Use and utility of preoperative hemostatic screening and patient history in adult neurosurgical patients. J Neurosurg. 2012 May;116(5):1097-105. 11. Dutzmann S, Gessler F, Marquardt G, Seifert V, Senft C. On the value of routine prothrombin time screening in elective neurosurgical procedures. Neurosurg Focus. 2012 Nov;33(5):E9. 12. van Gelder FE, de Graaff JC, van Wolfswinkel L, van Klei WA. Preoperative testing in noncardiac surgery patients: A survey amongst european anaesthesiologists. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2012 Oct;29(10):465-70. 13. Patey AM, Islam R, Francis JJ, Bryson GL, Grimshaw JM, Canada PRIME Plus Team. Anesthesiologists' and surgeons' perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: Application of the theoretical domains framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians' decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implement Sci. 2012 Jun 9;7:52,5908-7-52. 14. Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters, Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation, Pasternak LR, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force on preanesthesia evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2012 Mar;116(3):522-38. 15. Douglas PS, Khandheria B, Stainback RF, Weissman NJ, Peterson ED, Hendel RC, et al. ACCF/ASE/ACEP/AHA/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR 2008 appropriateness criteria for stress echocardiography: A report of the American College of Cardiology foundation appropriateness criteria task force, American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance: Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Circulation. 2008 Mar 18;117(11):1478-97. 16. Lamont T, Coates T, Mathew D, Scarpello J, Slater A. Checking for pregnancy before surgery: Summary of a safety report from the National Patient Safety Agency. BMJ. 2010 Jul 6;341:c3402. 17. Vigoda MM, Sweitzer B, Miljkovic N, Arheart KL, Messinger S, Candiotti K, et al. 2007 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines on perioperative cardiac evaluation are usually incorrectly applied by anesthesiology residents evaluating simulated patients. Anesth Analg. 2011 Apr;112(4):940-9.