ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Supplemental

advertisement

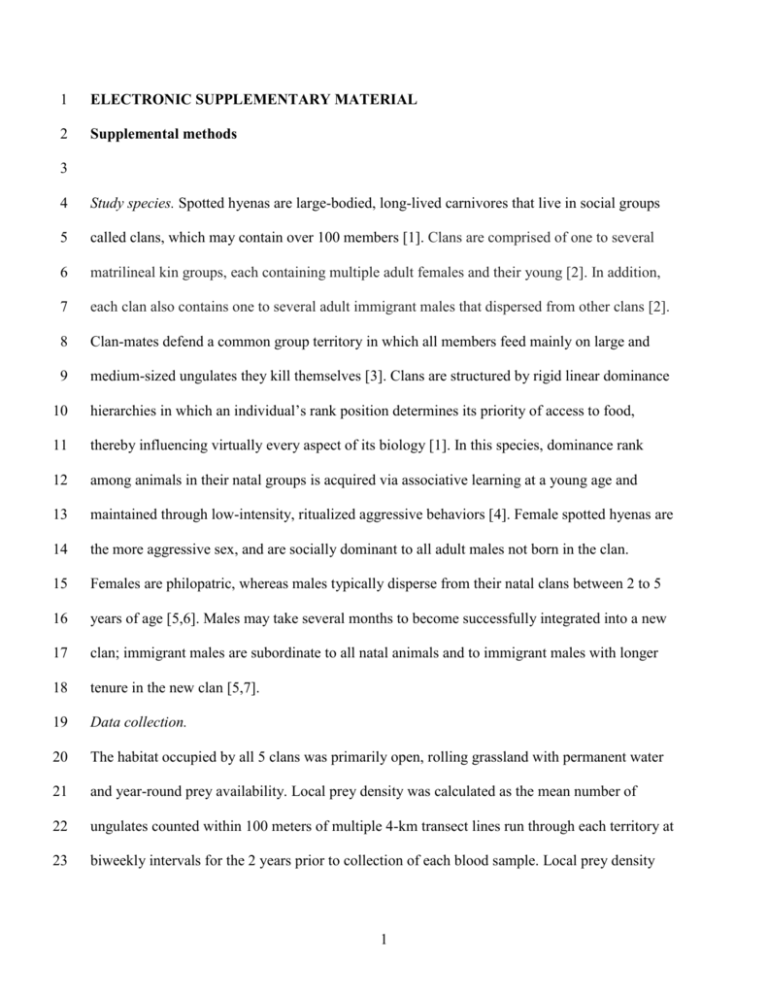

1 ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 2 Supplemental methods 3 4 Study species. Spotted hyenas are large-bodied, long-lived carnivores that live in social groups 5 called clans, which may contain over 100 members [1]. Clans are comprised of one to several 6 matrilineal kin groups, each containing multiple adult females and their young [2]. In addition, 7 each clan also contains one to several adult immigrant males that dispersed from other clans [2]. 8 Clan-mates defend a common group territory in which all members feed mainly on large and 9 medium-sized ungulates they kill themselves [3]. Clans are structured by rigid linear dominance 10 hierarchies in which an individual’s rank position determines its priority of access to food, 11 thereby influencing virtually every aspect of its biology [1]. In this species, dominance rank 12 among animals in their natal groups is acquired via associative learning at a young age and 13 maintained through low-intensity, ritualized aggressive behaviors [4]. Female spotted hyenas are 14 the more aggressive sex, and are socially dominant to all adult males not born in the clan. 15 Females are philopatric, whereas males typically disperse from their natal clans between 2 to 5 16 years of age [5,6]. Males may take several months to become successfully integrated into a new 17 clan; immigrant males are subordinate to all natal animals and to immigrant males with longer 18 tenure in the new clan [5,7]. 19 Data collection. 20 The habitat occupied by all 5 clans was primarily open, rolling grassland with permanent water 21 and year-round prey availability. Local prey density was calculated as the mean number of 22 ungulates counted within 100 meters of multiple 4-km transect lines run through each territory at 23 biweekly intervals for the 2 years prior to collection of each blood sample. Local prey density 1 24 was available for only 1 year prior to sample collection for one high-ranking female from the Fig 25 Tree clan and two high-ranking females from the Mara River clan. Per capita prey abundance 26 was calculated as mean local prey density divided by the mean number of adults present within 27 the respective clan during the 2 years prior to collection of each blood sample. Adults included 28 all immigrant males, natal males older than 3 years, and females who were at least 3 years of age 29 or who had borne their first litter, whichever came first. Within each clan, dominance rank 30 matrices were constructed based on outcomes of dyadic agonistic interactions [2]. We 31 standardized dominance rank to account for variation in clan size at time of darting; the 32 individual with a relative rank of 1 was the highest-ranking animal in the clan, and the individual 33 with a relative rank of -1 was the lowest-ranking. Except within matrilines, natal clan-mates are 34 no more closely related than are immigrant male hyenas, which originate in many different clans 35 [8]. Thus, among both natal females from different matrilines and male immigrants, relatedness 36 is effectively zero [8]. It is rare for males to remain within their natal clans long after sexual 37 maturity, so we were only able to obtain four telomere samples from three adult natal males. 38 Hyenas were immobilized using Telazol (Zoetis, South Bend, IN; 6.5 mg/kg) administered via a 39 lightweight plastic dart fired from a CO2-powered rifle (Telinject Inc., Saugus, CA). Blood 40 samples were collected from the jugular vein into EDTA-treated vacutainers and promptly frozen 41 in liquid nitrogen until they could be shipped on dry ice to Michigan State University where they 42 were stored at -80°C. 43 Telomere analysis: Genomic DNA was extracted using DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kits (Qiagen, 44 Valencia, CA) and kept frozen at -80°C until telomere analysis. Once shipped on dry ice to 45 Bucknell University, DNA was digested overnight with HinfI and RsaI, and separated using 46 pulsed field gel electrophoresis (3 V cm-1, 0.5-7.0 s switch times, 14°C) for 21 hours, followed 2 47 by in-gel hybridization at 37°C overnight with a radioactive-labelled telomere-specific oligo 48 (CCCTAA)4. Gels were then placed on a phosphorscreen (Amersham Biosciences, 49 Buckinghamshire, UK), which was scanned on a Storm 540 Variable Mode Imager (Amersham 50 Biosciences). Position and strength of the radioactive signal were determined by densitometry 51 using IMAGEQUANT 5.03v and IMAGEJ 1.42q. Mean telomere length was calculated using 52 the formula: L = Σ(ODi x Li)/ Σ(ODi) where ODi is the densitometry output at position i and Li is 53 the length (in basepairs) of the DNA at position i. For all samples, DNA integrity was evaluated 54 empirically by a nucleic acid stain following agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA was deemed 55 suitable for TRF length analysis if it was characterized as “a single compact crown-shaped band 56 that migrates in parallel with the other samples on the gel” [9]. Two control hyena samples were 57 run twice in each gel to determine intra- (2.8%) and inter-assay variability (3.2%). 58 59 60 References 1. Holekamp KE, Smith JE, Strelioff CC, Van Horn RC, Watts HE. 2012. Society, 61 demography and genetic structure in the spotted hyena. Mol. Ecol. 21, 613–632. (doi: 62 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05240.x) 63 64 65 66 67 2. Frank LG. 1986. Social organization of the spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta). II. Dominance and reproduction. Anim. Behav, 34, 1510–1527. 3. Kruuk H. 1972. The spotted hyena: a study of predation and social behaviour. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 4. Smale L, Frank LG, Holekamp KE. 1993. Ontogeny of dominance in free-living spotted 68 hyaenas: juvenile rank relations with adult females and immigrant males. Anim. Behav. 69 46, 467–477. 3 70 71 5. Holekamp KE, Smale L. 1998. Dispersal status influences hormones and behavior in the male spotted hyena. Horm. Behav. 33, 205–216. (doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1450) 72 6. Van Horn RC, McElhinny TL, Holekamp KE. 2003. Age estimation and dispersal in the 73 spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta). J Mammal. 84, 1019–1030. (doi: 10.1644/BBa-023) 74 7. East, ML, Hofer H. 2001. Male spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) queue for status in 75 social groups dominated by females. Behav. Ecol. 12, 558–568. (doi: 76 10.1093/beheco/12.5.558) 77 8. Van Horn RC, Engh AL, Scribner KT, Funk SM, Holekamp KE. 2004. Behavioral 78 structuring of relatedness in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) suggests direct fitness 79 benefits of clan-level cooperation. Mol. Ecol. 13, 449-458. 80 9. Kimura M, Stone RC, Hunt SC, Skurnick J, Lu X, Cao X, Harley CB, Aviv A. 2010. 81 Measurement of telomere length by the Southern blot analysis of terminal restriction 82 fragment lengths. Nat. Protoc. 5, 1596–1607. (doi: doi:10.1038/nprot.2010.124) 83 84 4 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 Table S1. Information on repeated samples from the same individuals. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Hyena ID Clan Age1 (yr) ali eco guci mrph bail hex nav ldv oak Talek Mara River Talek Talek Talek Talek Talek Talek Talek 3.93 5.02 3.43 2.72 7.91 4.29 6.45 3.50 2.52 Age2 (yr) 9.24 5.32 6.51 3.72 11.28 7.42 9.71 7.57 7.84 Age3 (yr) 13.04 - Table S2. Information on the demography and territories of sampled clans. Talek Serena North Mara River Serena South Fig Tree years sampled 1999-2013 2012-2013 2002-2009 2012-2013 2006-2009 mean territory size 57.3 km2 50 km2 31 km2 28 km2 52.91 km2 mean prey density per adult hyena 2.46 animals/ hyena 6.48 animals/ hyena 5.22 animals/ hyena 4.23 animals/ hyena 4.88 animals/ hyena Table S3. Results from a simple linear regression of offspring adult telomere length on maternal telomere length (df = 7). intercept maternal telomere length estimate 11.71 0.17 s.e. 2.82 0.19 5 t-value 4.16 0.93 p-value 0.004 0.39 R2 0.11