Annual Report 2012-13

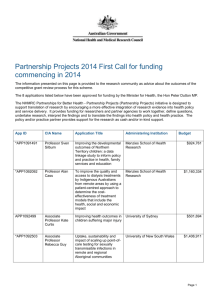

advertisement