A Brief History of the Khmer Rouge

advertisement

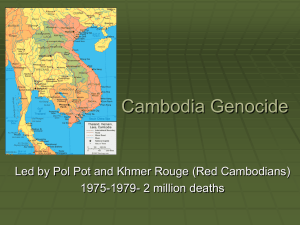

A Brief History of the Khmer Rouge By Dan Fletcher The Khmer Rouge killed nearly two million Cambodians from 1975 to 1979, spreading like a virus from the jungles until they controlled the entire country, only to systematically dismantle and destroy it in the name of a Communist agrarian ideal. Today, more than 30 years after Vietnamese soldiers removed the Khmer Rouge from power, the first genocide trials will start — a bittersweet note of progress in an impoverished nation still struggling to rehabilitate its crippled economic and human resources. The Khmer Rouge took root in Cambodia's northeastern jungles as early as the 1960s, a guerrilla group driven by communist ideals that nipped the periphery of governmentcontrolled areas. The flash point came when Cambodia's leader, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, was deposed in a military coup in 1970 and leaned on the Khmer Rouge for support. The prince's imprimatur lent the movement legitimacy, although while he would nominally serve as head of state, he spent much of the Khmer Rouge's rule under house arrest. As the country descended into civil war, the Khmer Rouge presented themselves as a party for peace and succeeded in mobilizing support in the countryside. (See pictures of spiritual healing around the world.) The pacifist talk belied a sinister agenda, one that would remain hidden to the outside world for years. When the Khmer Rouge succeeded in capturing the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh in 1975, they evacuated the entire population of the city — more than 2.5 million people — to camps in the countryside. Similar evacuations took place every time the Khmer Rouge took over a new city. Simultaneously, the Khmer Rouge were planning the steps necessary for a radical shift to an agrarian society. During the Khmer Rouge's nascent days, the movement's leader, Pol Pot, had grown to admire the way the tribes on the outskirts of Cambodia's jungles lived, free of Buddhism, money or education, and now he wanted to foist the same philosophy on the entire nation. Pol Pot envisioned a Cambodia absent of any social institutions like banks or religions or any modern technology. He sought to triple agricultural production in a year, absent the manpower or means necessary. On a visit to China in 1975, two Khmer Rouge members bragged they would "be the first nation to create a completely Communist society without wasting time on intermediate steps." It was deadly arrogance. With the cities emptied and the population under Khmer Rouge control, Pol Pot's means of implementation was to begin exterminating anyone who didn't fit this new ideal. He declared that he was turning Cambodia — now renamed the Democratic Republic of Kampuchea — back to "Year Zero," and intellectuals, businessmen, Buddhists and foreigners were all purged. "What is rotten must be removed," read a popular Khmer Rouge slogan at the time, and remove they did, often by execution but sometimes simply by working people to death in the fields. It's impossible to tally the total number dead with any precision, but it is generally assumed that the Khmer Rouge killed between one million and two million people during their reign. Thousands more died of malnutrition or disease, and the upper classes of Cambodian society were all but wiped out. The killing continued unabated until Vietnamese troops, tired of border skirmishes with the Khmer Rouge, invaded in 1979 and sent the Khmer Rouge back to the jungles. Pol Pot continued to lead the Khmer Rouge as an insurgent movement until 1997, when he was arrested and sentenced to house arrest by his own followers after killing one of his closest advisers. He died in 1998 in a tiny jungle village, never having faced charges. Now, five leaders of the Khmer Rouge will face charges in a tribunal backed by the United Nations. The first, Kaing Guek Eav — known better by his nom de guerre, Duch — ran the Tuol Sleng prison camp in Phnom Penh, where out of 17,000 Cambodians who were imprisoned, fewer than 20 survived. Pol Pot's second-in-command, Nuon Chea, will also face charges, as well as the Khmer Rouge's former foreign minister and head of state. But some are already questioning the integrity of the tribunal, which was tasked only with bringing those "most responsible" for the genocide to justice. Many victims' families say limiting the blame to these five alone is not enough, and human rights experts say that more comprehensive trials may help a country desperately in need of healing.

![Cambodian New Year - Rotha Chao [[.efolio.]]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005298862_1-07ad9f61287c09b0b20401422ff2087a-300x300.png)