Pol Pot: The Early Years

advertisement

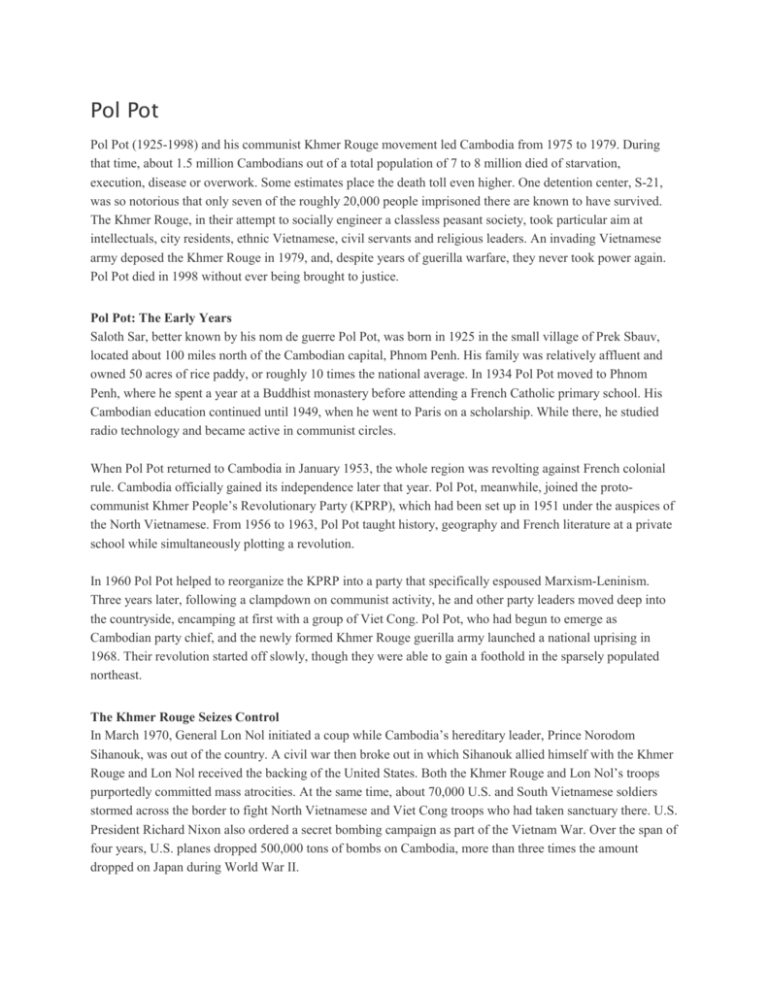

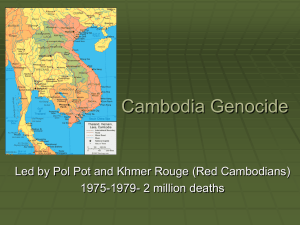

Pol Pot Pol Pot (1925-1998) and his communist Khmer Rouge movement led Cambodia from 1975 to 1979. During that time, about 1.5 million Cambodians out of a total population of 7 to 8 million died of starvation, execution, disease or overwork. Some estimates place the death toll even higher. One detention center, S-21, was so notorious that only seven of the roughly 20,000 people imprisoned there are known to have survived. The Khmer Rouge, in their attempt to socially engineer a classless peasant society, took particular aim at intellectuals, city residents, ethnic Vietnamese, civil servants and religious leaders. An invading Vietnamese army deposed the Khmer Rouge in 1979, and, despite years of guerilla warfare, they never took power again. Pol Pot died in 1998 without ever being brought to justice. Pol Pot: The Early Years Saloth Sar, better known by his nom de guerre Pol Pot, was born in 1925 in the small village of Prek Sbauv, located about 100 miles north of the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh. His family was relatively affluent and owned 50 acres of rice paddy, or roughly 10 times the national average. In 1934 Pol Pot moved to Phnom Penh, where he spent a year at a Buddhist monastery before attending a French Catholic primary school. His Cambodian education continued until 1949, when he went to Paris on a scholarship. While there, he studied radio technology and became active in communist circles. When Pol Pot returned to Cambodia in January 1953, the whole region was revolting against French colonial rule. Cambodia officially gained its independence later that year. Pol Pot, meanwhile, joined the protocommunist Khmer People’s Revolutionary Party (KPRP), which had been set up in 1951 under the auspices of the North Vietnamese. From 1956 to 1963, Pol Pot taught history, geography and French literature at a private school while simultaneously plotting a revolution. In 1960 Pol Pot helped to reorganize the KPRP into a party that specifically espoused Marxism-Leninism. Three years later, following a clampdown on communist activity, he and other party leaders moved deep into the countryside, encamping at first with a group of Viet Cong. Pol Pot, who had begun to emerge as Cambodian party chief, and the newly formed Khmer Rouge guerilla army launched a national uprising in 1968. Their revolution started off slowly, though they were able to gain a foothold in the sparsely populated northeast. The Khmer Rouge Seizes Control In March 1970, General Lon Nol initiated a coup while Cambodia’s hereditary leader, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, was out of the country. A civil war then broke out in which Sihanouk allied himself with the Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol received the backing of the United States. Both the Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol’s troops purportedly committed mass atrocities. At the same time, about 70,000 U.S. and South Vietnamese soldiers stormed across the border to fight North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops who had taken sanctuary there. U.S. President Richard Nixon also ordered a secret bombing campaign as part of the Vietnam War. Over the span of four years, U.S. planes dropped 500,000 tons of bombs on Cambodia, more than three times the amount dropped on Japan during World War II. By the time the U.S. bombing campaign ended in August 1973, the number of Khmer Rouge troops had increased exponentially, and they now controlled approximately three-quarters of Cambodia’s territory. Soon after, they began shelling Phnom Penh with rockets and artillery. A final assault of the refugee-filled capital started in January 1975, with the Khmer Rouge bombarding the airport and blockading river crossings. A U.S. airlift of supplies failed to prevent thousands of children from starving. Finally, on April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge entered the city and ended the fighting. About half a million Cambodians had died during the civil war, yet the worst was still to come. Life Under the Khmer Rouge Almost immediately after taking power, the Khmer Rouge evacuated Phnom Penh’s 2.5 million residents. Former civil servants, doctors, teachers and other professionals were stripped of their possessions and forced to toil in the fields as part of a reeducation process. Those that complained about the work, concealed their rations or broke rules were usually tortured in a detention center, such as the infamous S-21, and then killed. The bones of people who died from malnutrition or inadequate healthcare also filled up mass graves across the country. Under Pol Pot, the state controlled all aspects of a person’s life. Money, private property, jewelry, gambling, most reading material and religion were outlawed; agriculture was collectivized; children were taken from their homes and forced into the military; and strict rules governing sexual relations, vocabulary and clothing were laid down. The Khmer Rouge, which renamed the country Democratic Kampuchea, even insisted on realigning rice fields in order to create the symmetrical checkerboard pictured on their coat of arms. At first, Pol Pot largely governed from behind the scenes. He became prime minister in 1976 after Sihanouk resigned. By that time, border skirmishes were occurring regularly between the Cambodians and the Vietnamese. The fighting intensified in 1977, and in December 1978 the Vietnamese sent more than 60,000 troops, along with air and artillery units, across the border. On January 7, 1979, they captured Phnom Penh and forced Pol Pot to flee back into the jungle, where he resumed guerilla operations. Pol Pot's Final Years Throughout the 1980s, the Khmer Rouge received arms from China and political support from the United States, which opposed the decade-long Vietnamese occupation. But the Khmer Rouge’s influence began to decrease following a 1991 ceasefire agreement, and the movement completely collapsed by the end of the decade. In 1997 a Khmer Rouge splinter group captured Pol Pot and placed him under house arrest. He died in his sleep on April 15, 1998, due to heart failure. To date, a United Nations-backed tribunal has convicted only one Khmer Rouge leader of crimes against humanity.

![Cambodian New Year - Rotha Chao [[.efolio.]]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005298862_1-07ad9f61287c09b0b20401422ff2087a-300x300.png)