Morcom, Terrains of Bollywood dance, post print

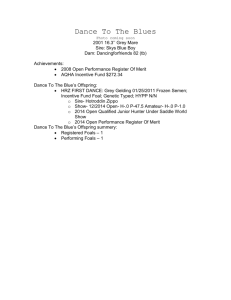

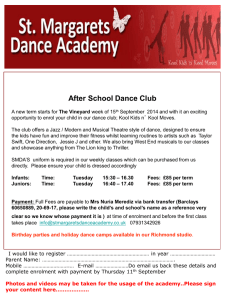

advertisement