Gossman This is an excellent paper! The errors are primarily formal

advertisement

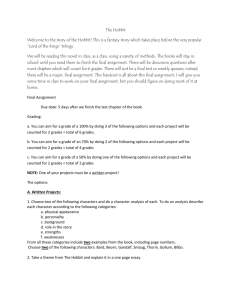

Gossman 1 This is an excellent paper! The errors are primarily formal. I corrected errors the first time I encountered them and put a note for you to correct throughout. Consider revising the thesis statement and the conclusion a little to draw together your observations, but this is otherwise very complete – revisions are very minor! Enjoyed reading it! Danny Gossman Dr. Abigail Heiniger English 2120 - Intro to Fiction 20 March 2013 The Hobbit: Setting the Stage for the English Hero It is almost impossible to tell a story without using an idea that has already been used for other stories. The phrase, “once upon a time” is so often used that the mere mention of it can let an audience know that a fairy tale is about to be told. It is not to say that an author that does this has a lack for originality--if this were the case, all modern stories would simply be retellings of older stories. Rather, using ideas or elements of other cultures or from stories of different cultures can be an effective method to create an original story of one’s own. Sometimes, using elements from other types of fiction may go unnoticed because they have been embedded very well into a story. It’s like throwing together a bunch of ingredients and cooking them perfectly to make a surprisingly delicious meal--it just works. When this is the case and a story makes sense, the potential for the author to convey a certain message can be truly something special because, often, the blending together of many elements of different types of fiction is entertaining as well, keeping the reader glued to the story. J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Hobbit (1937), exemplifies this type of procedure. Tolkien uses elements of Norse Gossman 2 and Anglo-Saxon mythology to construct a new world that invites readers to explore the means of Bilbo Baggins’ maturation into a hero, ultimately constructing the ideal hero to his primary audience of pre-World War II-era English children. J.R.R. Tolkien studied many different types of folklore and mythology. According to "Middle Earth in the Classroom: Studying J. R. R. Tolkien" (1969) by Richard Roos, “Tolkien knew the myths of the far east and the near east. He was eminently familiar with the Graeco-Roman myths of Troy and Olympus, as well as the drama of the Golden Age. And he was versed in the Anglo-Saxon near myths of Arthur and Beowulf” (8). Tolkien’s extensive use of mythology in The Hobbit can be easily understood when thinking of it like this: Tolkien lived in a world that was different from the worlds he studied. Consequently, The Hobbit reflects this. This merging of worlds, both in terms of the worlds between his studies and his real life, and the merging of worlds to create middle earth, allows Tolkien to immerse his readers into his story so that he can develop his main character, Bilbo Baggins, into a hero. This does not mean that Tolkien had a lack for originality though “As Tolkien noted in his famous essay ‘On Fairy Tales’ (1965), creators of individual tales get their materials and techniques from what he called ‘the Cauldron of Story.’ That is, an author’s originality consists mainly of what s/he does with materials and techniques s/he did not invent” (5; 138). THIS WOULD BE A GREAT PLACE TO EXPAND A LITTLE. Perhaps follow up with a sentence analyzing (in your words) what “the Cauldron of Story” means. Throughout The Hobbit, the reader is introduced to a plethora of different races. From the start, Tolkien introduces hobbits, “little people, about half our height and smaller than the bearded dwarves” (Tolkien 4) and gives a brief description of Bilbo Baggins. Soon after, dwarves Gossman 3 come into the story. Whereas hobbits are created by Tolkien, dwarves constitute a race of characters that Tolkien borrowed from Norse mythology. As noted by Martin Wettstein, “Norse Dwarves live in caves and mines in the mountains where they dig for gold and gems.” Consequently, Wettstein notes that Tolkien used an old Norse poem to name the dwarves as well, that poem being called “The Völuspá and is the first poem of the poetic Edda.” The main purpose of dwarves in The Hobbit is to force Bilbo Baggins into an uncomfortable situation, something that he is not used to. Once he is put in dangerous situations, he is able to overcome his anxieties and eventually lead the dwarves to the mountain in which they are seeking to regain their rightful treasure from. Moreover, the dwarves’ increased trust and overall attitude towards Bilbo reflects his ongoing ascension into a hero. At the beginning of their journey, the dwarves are skeptical of the reserved Bilbo. As the story progresses and Bilbo proves himself in difficult situations, the dwarves’ attitudes toward Bilbo becomes increasingly honorable. For example, Tolkien narrates that if the dwarves “had still doubted that he was really a first-class burglar” after Bilbo makes it out of the caverns in the Misty Mountains alive, “in spite of Gandalf’s words, they doubted no longer” (Tolkien 103). Furthermore, the fact that Bilbo has to lead a large amount of dwarves, 14 of them--which is also taken directly from Beowulf, in which the hero goes on a journey with fourteen companions (2; 179)--to their destination heightens the expectations put on him, setting the stage for an accentuated rise to heroism. Dwarves serve a major function in terms of Bilbo’s development, but other races such as trolls provide challenges to Bilbo on his quest. The Trolls that Bilbo and the dwarves encounter in the woods are the first adversaries that test Bilbo on the quest. When they realize that Gandalf is not present in their then-current Gossman 4 debacle, the dwarves turn to Bilbo: “‘Now it is the burglar’s turn,’ they said, meaning Bilbo. ‘You must go on and find out all about that light, and what it is for, and if all is perfectly safe and canny,’ said Thorin to the hobbit” (Tolkien 38). As a reserved hobbit not used to adventure, this is a huge task for Bilbo. Still, Bilbo proceeds and symbolically begins his quest for courage when he reaches his hand into one of the trolls’ pockets: “‘Ha!’ thought he, warming to his new work as he lifted it carefully out, ‘this is a beginning!’” (Tolkien 40). This symbolically represents the beginning of two things: Bilbo taking the first courageous step into moving past his apprehensiveness and the beginning of the adversaries that he is going to encounter. The trolls are not that difficult to get past in the whole context of Bilbo’s quest in The Hobbit; as John C. Stotts notes, “Bilbo’s adversaries become progressively more clever and dangerous. Only because his wisdom and experience increase does he become a fit match for them. Had he met Smaug at first, the adventure would have been quickly terminated” (5; 140). The trolls provide another example of how Tolkien uses Norse folklore elements to help aid Bilbo’s development, albeit their purpose is to allow Bilbo to first dip his toes into the water of courage and heroism. Dwarves and trolls are merely examples of Norse races that Tolkien brings into The Hobbit; but one of the biggest aspects that Tolkien borrows from Norse folklore is the idea of a powerful dragon. Wettstein contends that “the Dragons also appear in the Norse Mythology. Norse Dragons lived in caves and protected their treasures. Their only weak spot was their belly.” This is clearly reflected in Smaug, the all-powerful dragon of The Hobbit that guards the dwarves’ treasure under the mountain. Smaug also has a weak spot, which is exploited by Bard when An old thrush came to Bard and told him, “The moon is rising. Look for the hollow of the left breast Gossman 5 as he flies and turns above you!” (Tolkien 270). At that moment Bard, a human, destroys Smaug by striking him in his weak spot on his belly. While Smaug fits the description that Wettstein says is sufficient to take on the identity of a Norse element, it is perhaps important to note that Tolkien was more likely to have been influenced by works of Anglo-Saxon folklore instead when getting the idea of the dragon. As previously noted, Tolkien is a thorough scholar of Beowulf, an Anglo-Saxon epic that includes a dragon strikingly similar to Smaug. As a scholar of Beowulf, Tolkien meticulously studied Anglo-Saxon folklore (8; 1179), allowing him to incorporate the idea of a talking dragon into his work. For example, a hero named Sigurd slayed a dragon similar to Smaug: “His greatest deed of courage was the slaying of Fafnir, the dragon, who dwelt in the cold dank caves of which he was a part, guarding his stolen treasure hoard” (2; 179). This shows how Tolkien got the idea of Smaug guarding treasure: “Smaug lay, with wings folded like an immeasurable bat, turned partly on one side, so that the hobbit could see his underparts and his long pale belly crusted with gems and fragments of old from his long lying on his costly bed” (Tolkien 233). Even more relevant is the comparison of Smaug to the Fire-eater dragon in Beowulf. In this epic, the dragon “went on his rampage only when a slave pilfered a golden cup from the hoard which the serpent had been guarding for 300 years” (2; 179). One can tell that Tolkien took this straight from Beowulf when looking at the moment when Smaug “stirred and stretched forth his neck to sniff. Then he missed the cup!” (Tolkien 236) and immediately went “to hunt the whole mountain till he had caught the thief and had torn and trampled him was his one thought” (Tolkien 236). Overall, the purpose of a talking, powerful dragon in The Hobbit is to put Bilbo’s development into perspective. To elaborate, Bilbo starts out as a personality that is attached to his little hobbit Gossman 6 hole, devoid of any adventures into the outside world of middle-earth. Compare that Bilbo with the Bilbo who says ‘Confound you, Smaug, you worm!’ he squeaked aloud. ‘Stop playing hideand-seek! Give me a light, and then eat me, if you can catch me!’” (Tolkien 255) towards the conclusion of the novel. Clearly, the comparison between Bilbo at the beginning of the novel and Bilbo at the end is a huge change in terms of courage. A dragon is a very intimidating figure, especially a talking one with almost impenetrable armor. Therefore, it is easy to see how Bilbo has come a long way when looking at his willingness to tempt the dragon to come out and eat him, something that never would have been in the confines of his mind at the beginning. The dragon is just one example of Tolkien’s incorporation of Anglo-Saxon folklore elements into the novel though. Others, such as swords, are key Anglo-Saxon features that help the reader understand Bilbo’s development as well. In Anglo-Saxon folklore, swords have a big impact. Firstly, it is commonplace in Old English to assign names to swords. For example, in Beowulf, Beowulf inherits a sword named Hrunting. Paralleling this is the naming of swords in The Hobbit. For example, Thorin’s sword is named “Orcrist, Goblin-cleaver, but the goblins called it simply Biter” (Tolkien 73). Similarly, Gandalf possesses a sword named “Glamdring the Foe-hammer” (Tolkien 73) that “had no trouble whatever of cutting through the goblin-chains and setting all the prisoners free as quickly as possible” (tolkien 73). The fact that Gandalf’s sword was so easily able to defeat the goblins is something to be noted; Gandalf is already a proven figure of courage. If swords represent heroism in the novel, then it makes sense that Bilbo’s sword isn’t as powerful at this point in the early stages of the story. Later in the novel, when Bilbo is more developed on his progress towards heroism, he goes to combat with his sword against the spiders. When “the Gossman 7 spider lay dead beside him, and his sword-blade was stained black... He felt a different person, and much fiercer and bolder in spite of an empty stomach, as he wiped his sword on the grass and put it back into its sheath” (Tolkien 170). In this case, Bilbo’s sword mirrors his development and symbolizes the next step that he takes towards becoming a truly courageous hobbit. At that point, Bilbo names his sword “Sting” (Tolkien 170). Bilbo’s naming of his sword marks his newfound capacity to take on bigger challenges, as he does throughout the rest of the novel. Beyond the actual naming of swords in The Hobbit, Tolkien borrows a significant element of swords from Beowulf to contribute to his construction of the ideal hero to his readers. Tolkien not only borrows the Anglo-Saxon tradition of sword-naming but the also AngloSaxon sword-fight etiquette: both Bilbo and Beowulf refuse to strike an adversary if he is unarmed. For example, According to Taylor Culburt of The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, “There is no reason to doubt Beowulf’s good faith: he refuses to fight with a sword, not because he knows that it would not bite through Grendel’s tough hide and not because he himself is naturally disposed to hug his adversary to death but because he hopes to place both combatants on an equal footing” (9; 14). With this in mind, it is clear where Tolkien got his idea to give Bilbo an apprehensiveness to strike the unarmed Gollum in the caverns: “He must fight. He must stab the foul thing, put its eyes out, kill it. It meant to kill him. No, not a fair fight. He was invisible now. Gollum had no sword. Gollum had not actually threatened to kill him, or tried to yet” (Tolkien 96). Here, Tolkien borrowed this idea of apprehensiveness to fighting unfairly in order to do the cultural work of constructing the idea of a morally righteous hero to his readers; in other words, fighting unfairly is wrong. He also uses the Anglo-Saxon folklore Gossman 8 element of riddles to offer an alternative to physical violence. Because Bilbo is able to escape Gollum through the use of riddles rather than using the violence of the sword, Tolkien is suggesting to readers that a hero’s wit and charisma is just as useful as his ability to wield weapons in overcoming adversaries. Though Tolkien uses elements of other types of folklore, particularly Norse and Old English, he does so in a way that presents his story as matter-of-fact; in other words, it is difficult to notice that his story is fictional because he makes it easy to understand. One way in which he does this is through the use of narrative asides to help guide the reader through the novel. Throughout The Hobbit, Tolkien pauses his narration to give his readers some information about what is going on. This is particularly helpful to children readers who may not be as inclined to dig deep into each particular scene to figure out the context of what’s happening. For example, at the very beginning of the novel, the reader can see that Tolkien uses an aside to aid in character development: “Gandalf! If you had heard only a quarter of what I have heard about him, and I have only heard very little of all there is to hear, you would be prepared for any sort of remarkable tale” (Tolkien 6). This subtle-yet-personal message to the reader gives him or her the idea that Gandalf is a mysterious figure, something that is important to keep in mind as the novel progresses because Gandalf constantly wades in and out of the action that goes on with Bilbo and the dwarves. Another example of Tolkien’s use of asides can be seen in chapter five, when Tolkien says to the reader, “I imagine you know the answer, since you are sitting comfortably at home and have not the danger of being eaten to disturb your thinking” (Tolkien 85), referring to the context between Bilbo’s struggle to figure out one of Gollum’s riddles and the reader’s situation at home or wherever he or she is reading. Gossman 9 In this case, the aside is used to magnify the tension that Bilbo feels when confronted with such a riddle; by putting it in perspective and comparing Bilbo’s situation to the reader’s, Tolkien makes the reader conscious of the pressure that Bilbo feels. This, ultimately, emphasizes what Bilbo has to overcome to come out successful in a particular situation. When the reader understands this, he or she can understand more clearly how Bilbo develops as a character into a courageous hero. Finally, Tolkien uses asides in the novel to contribute to the matter-offactness of middle earth. For example, he describes the race of the eagles as “not kindly birds. Some are cowardly and cruel. But the ancient race of the northern mountains were the greatest of all birds” (Tolkien 114). By pausing the story to identify the readers with this particular race of characters and presenting it to them in a matter-of-fact way, the reader is inclined to feel that these eagles are real in the context of the novel. Narrative asides can be an effective tool in bringing together the different elements of other types of folklore simply because they allow Tolkien to identify with the readers and make it easier for them to understand. All of this contributes to a smooth, easily-understandable story that tracks the development of Bilbo’s ascension into heroism. Why does it even matter though? Tolkien’s seemingly perfect blend of several elements of other types of folklore to create his own world yields a significant result: the ideal setting for Bilbo Baggins to transform into an unlikely hero. It’s easy to see Bilbo’s ascension into a hero when taking a look at the Bilbo character compared from the beginning to the end, “comparing the comfort-loving, wellto-do, respectable, and somewhat lazy Bilbo of the opening with the hobbit who, at the conclusion, has lost his reputation and doesn’t care” (5; 138). Key changes in Bilbo’s character include a loss of conscious about his reputation among other hobbits, a lessened dependence Gossman 10 on luck to get him through sticky situations, and a willingness to assume leadership among the dwarves. What makes these changes even more significant though is the fact that Bilbo does not lose his identity as a comfort-loving hobbit who enjoys his home in the hobbit hole. By having Bilbo survive all of these adventures and returning home with a heightened sense of adventure, Tolkien is suggesting to his children readers that it is okay to step out of their comfort zone; in order to discover oneself, he or she has to take risks. Those risks will not inherently change the makeup of him or her, but rather they will expand the knowledge of oneself to the point where courage is a primary characteristic. This is what Bilbo Baggins represents: the ideal, yet unlikely hero in English society in the 1930s before World War II. Although Bilbo is merely a fictional character in a fantastic world, Tolkien’s way of making his created world seem so real tugs at his readers a little bit. Perhaps readers who are completely engrossed in The Hobbit can make a connection to Bilbo Baggins--seeing that he is a likeable character--and therefore subconsciously get the idea that they can be just like him. It’s not to say that readers really believe they can become courageous hobbits who take on trolls and dragons, but rather they can understand that courage lies within themselves. By making Bilbo a likeable character, Tolkien is able to convey to his readers what an ideal Englishman should be like. First off, Tolkien may be suggesting that the ideal hero is not inclined to violence. According to Ruth Stein, Tolkien “first told The Hobbit to his own children when World War II was looming” (2; 183). Therefore, it is not outrageous to conclude that Tolkien wanted his readers to understand that violence wasn’t necessary to be a war hero. For example, during the Battle of Five Armies, Bilbo “put on his ring early in the business and vanished from sight, if not from all danger” (Tolkien 305). Because Bilbo is the character that Tolkien constructed into a Gossman 11 hero, the common thought would be to think that he’d be all about war. However, because he sits to the side and wants nothing to do with it, Tolkien offers a different type of hero; an unlikely hero at that who stays away from the war. Besides nonviolence, Tolkien’s constructed idea of the English hero also assumes a specific type of value system. At the end of the Battle of Five Armies after Bilbo wakes up, he finds that Thorin is dying. Upon laying down to his death, he gives one of The Hobbit’s most famous quotes to Bilbo: “There is more good in you of good than you know, child of the kindly West. Some courage and some wisdom, blended in measure. If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world” (Tolkien 312). It is at this moment that the reader comes to realize that a strong desire for material items with no intrinsic good in them is a recipe for disaster. Thorin, who represents materialism and an earlier mythic tradition, ends up dying off. On the other hand, Bilbo, who represents the reserved Englishman who is content with goods of intrinsic value and a new mythic tradition, survives and returns to his original home with an added value of courage. This is Tolkien’s way of steering away from the common idea of a hero that is a warlike figure with dreams of capturing treasure. Again, because Tolkien blends all of the elements of other types of folklore together in a seemingly flawless pattern, readers get the feel that the novel is real; therefore, Tolkien’s constructed idea of a hero also feels real. Seeing that this all makes sense, what would the reader think if Tolkien simply said that he has no taste for allegory and that his story was simply for the sake of storytelling? On a number of occasions, J.R.R. Tolkien has denied that The Hobbit takes on any sort of allegorical meaning. For example, when critiquing an author named George MacDonald, Tolkien states that he was “displeased that MacDonald wrote allegories—a form he inherently disliked. Gossman 12 Tolkien explains,’But [C. S. Lewis] was evidently born loving (moral) allegory, and I was born with an instinctive distaste for it’” (11). Likewise, Ruth Stein notes that The Hobbit (as well as the rest of The Lord of the Rings trilogy) “have been interpreted in many ways, [nevertheless] they were not written as allegories, but as tales to entertain” (2; 183). In other words, Tolkien claims that his sole purpose for writing is for the sake of storytelling. Despite this, readers cannot disregard the mass amount of evidence that points to Tolkien’s creation of his own mythology as a type of cultural work for the English society that he lived in. His values towards heroism and materialism, for example, are clearly embedded into his characters in The Hobbit, as previously noted. Whatever the case may be, Tolkien’s incorporation of a multitude of different folklore elements allows him to get his themes across to his readers. Bilbo Baggins’ development into a hero while retaining his identity is a central theme to The Hobbit. Tolkien is able to convey this theme onto his readers so effectively because he is able to create his own world that puts Bilbo in the perfect situation to become a hero. Among the most prevalent influences to Tolkien are Norse folklore elements--such as dwarves and trolls--and Anglo-Saxon elements, particularly elements found in Beowulf. By incorporating these elements into one smooth story, Tolkien takes on the challenge of immersing his readers into the story and making them accept his created world as matter-of-fact. Because he succeeds in this aspect, his readers are able to understand that Bilbo’s development into a hero is a journey--a journey that takes him from the comfort of his hobbit hole to the confounds of a powerful dragon named Smaug. Because Bilbo is a likeable character, coupled by the fact that Tolkien’s story succeeds at making the reader feel that his created world is real, the reader can make a connection to Bilbo in regards to what it means to be an ideal man or hero. Gossman 13 Furthermore, Tolkien’s intended audience was children. Therefore, Tolkien is writing for the then-future of English society. One can assert that he is molding, in a way, the future generations to step out of their comfort zone and discover what they can do, just as Bilbo did. Bilbo’s retainment of his Baggins heritage and reservedness may alleviate any of the fears that his children may have of changing who they are if they step out of their comfort zone as well. Whatever the case may be, “It is because of both the traditional materials and his synthesis of them that Tolkien’s novels are the standard by which all of the others are judged” (6; 287). In another sense, Tolkien put all of the right ingredients into his work and mixed them together perfectly. The result? A seamless story with the power to influence children on what it means to become a hero. Bilbo is an INDIVIDUAL and the hobbits are a distinctive race just as the English mythology that Tolkien writes is distinctive. Think about this as you conclude (drawing your paper back to your original observations). Excellent paper! Enjoyed reading it! Gossman 14 Works Cited Culburt, Taylor. "The Narrative Functions of Beowulf's Swords." The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 59.1 (1960): 13-20. Print. Long, Josh. "Clinamen, Tessera, and the Anxiety of Influence: Swerving from and Completing George MacDonald." Tolkien Studies 6 (2009): n. pag. JSTOR. Web. 22 Mar. 2013. Roos, Richard. "Middle Earth in the Classroom: Studying J. R. R. Tolkien." The English Journal 8.58 (1969): 1175-180. JSTOR. Web. 19 Mar. 2013. Stein, Ruth M. "The Changing Styles in Dragons—from Fáfnir to Smaug." Elementary English 45.2 (1968): 179-83. JSTOR. Web. 1 Mar. 2013. Stott, John C. "A Structuralist Approach to Teaching Novels in the Elementary Grades." The Reading Teacher 36.2 (1982): 136-43. JSTOR. Web. 2 Mar. 2013. Sullivan, C.W., III. "Folklore and Fantastic Literature." Western Folklore 60.4 (2001): 279-96. JSTOR. Web. 19 Mar. 2013. Tolkien, J. R. R. The Hobbit, Or, There and Back Again. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012. Print. Gossman 15 Wettstein, Martin. "Norse Elements in the Work of J.R.R. Tolkien." Acadamia.edu (2002): n. pag. Oct. 2002. Web. 17 Mar. 2013.